“The Thursday Murder Club” (Penguin Books, 2020): For anyone advancing into middle age or beyond, getting older is no joke. In this witty  mystery, however, four seniors are undaunted, and, with time on their hands, they work together to solve cases that the police have given up on. Each brings unique skills to the task: Joyce is a retired nurse, the mysterious Elizabeth is possibly a former spy, Ron a former labor leader, and Ibrahim a semi-retired psychiatrist. They live in Coopers Chase, an upscale retirement village in Kent, meeting on Thursdays in the Jigsaw Room to solve cold cases and bring a measure of justice to murder victims. When a controversial developer is murdered on the grounds, the group is caught up in an active case, and we the readers come along for the ride. The author, Richard Osman, is rather a character in his own right. Well-known in Britain, he is a television personality, producer, and writer, a background he uses to good effect in this well-paced story, which is sympathetic, amusing, and engaging. “A little beacon of pleasure,” best-selling author Kate Atkinson calls it. And if you enjoy this book, there is good news: there are three sequels in the series! But wait, there’s more! A movie is in the works, with an all-star cast! But read the book first; it is a treat.

mystery, however, four seniors are undaunted, and, with time on their hands, they work together to solve cases that the police have given up on. Each brings unique skills to the task: Joyce is a retired nurse, the mysterious Elizabeth is possibly a former spy, Ron a former labor leader, and Ibrahim a semi-retired psychiatrist. They live in Coopers Chase, an upscale retirement village in Kent, meeting on Thursdays in the Jigsaw Room to solve cold cases and bring a measure of justice to murder victims. When a controversial developer is murdered on the grounds, the group is caught up in an active case, and we the readers come along for the ride. The author, Richard Osman, is rather a character in his own right. Well-known in Britain, he is a television personality, producer, and writer, a background he uses to good effect in this well-paced story, which is sympathetic, amusing, and engaging. “A little beacon of pleasure,” best-selling author Kate Atkinson calls it. And if you enjoy this book, there is good news: there are three sequels in the series! But wait, there’s more! A movie is in the works, with an all-star cast! But read the book first; it is a treat.

Review © 2025 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

***************************

“Coastal Nova Scotia: A Photographic Tour” (Nimbus Publishing, 2020): There is something captivating about the places where water meets land, nowhere more so than on the abundant shores of Nova Scotia. Here’s a visual tribute to what Canadian  singer/songwriter Stompin’ Tom Connors dubbed the ‘sea-bound coast’ of Nova Scotia, with ethereal ‘sea smoke’ wafting above Halifax harbor, the splendid isolation of the Sambro Island Lighthouse on its rocky promontory, the fabled wild horses of Sable Island, the famed headland at Peggy’s Cove, the daily tidal drama at the Bay of Fundy, and the Louisbourg Lighthouse shot beneath a resplendent Milky Way. There are coastal vistas, crashing waves, calm seas, sandy beaches, tiny islets, autumnal splendor (at Mahone Bay), occasional surfers, and ruggedly rocky outcroppings. And, of course, there’s Cape Breton, the irresistible place where mountains meet the sea, a place about which we’ve said: “The Cabot Trail is an organic thing – playful, daring, and exuberant as it swoops and turns, plunges and climbs, clinging to looming mountainsides, lingering by rocky shores, darting into immense woods, and boldly descending at break-neck angles toward the glistening sea. To traverse the trail is to ride the whale’s back, thrilling all the while at its wild life coursing beneath you.” British-expat Adam Cornick, a surfer by avocation and photographer by profession, has assembled an utterly delightful collection of images from one of our favorite places. His book is certain to please existing devotees of Nova Scotia and to win it many new ones.

singer/songwriter Stompin’ Tom Connors dubbed the ‘sea-bound coast’ of Nova Scotia, with ethereal ‘sea smoke’ wafting above Halifax harbor, the splendid isolation of the Sambro Island Lighthouse on its rocky promontory, the fabled wild horses of Sable Island, the famed headland at Peggy’s Cove, the daily tidal drama at the Bay of Fundy, and the Louisbourg Lighthouse shot beneath a resplendent Milky Way. There are coastal vistas, crashing waves, calm seas, sandy beaches, tiny islets, autumnal splendor (at Mahone Bay), occasional surfers, and ruggedly rocky outcroppings. And, of course, there’s Cape Breton, the irresistible place where mountains meet the sea, a place about which we’ve said: “The Cabot Trail is an organic thing – playful, daring, and exuberant as it swoops and turns, plunges and climbs, clinging to looming mountainsides, lingering by rocky shores, darting into immense woods, and boldly descending at break-neck angles toward the glistening sea. To traverse the trail is to ride the whale’s back, thrilling all the while at its wild life coursing beneath you.” British-expat Adam Cornick, a surfer by avocation and photographer by profession, has assembled an utterly delightful collection of images from one of our favorite places. His book is certain to please existing devotees of Nova Scotia and to win it many new ones.

Review © 2021 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: For our travel essay on Nova Scotia, visit: https://artsforum.ca/travel

***************************

“Evelyn’s Stories” by Pamela Williams (PMW Books, 2019): Canadian photographer Pamela Williams is best known for her  exquisitely evocative B&W photography. Here, she ventures into prose with a collection of short vignettes based on stories her mother told her over a lifetime, starting in Glasgow, Scotland in 1906 and ending in Toronto in 2018. These ostensibly true (though maybe occasionally tall) tales are instantly engaging stuff, infused with a wry sense of humor that’s reminiscent of the work of Ottawa Valley storyteller Mary Cook (who was long a staple on CBC Radio’s “Fresh Air”). There’s a down-to-earth quality to Williams’ unpretentious, ‘what you see is what you get’ cast of characters; and, their experiences, gleaned from the stuff of ordinary everyday life, is often accompanied by closing turns worthy of O. Henry himself. A matter of fact tone belies the gentle irony in accounts which are at once character-specific and effortlessly relatable. An 86-year-old driver navigates off-road mishaps with aplomb; a roller skater meets his fate in the form of a sewer grate; dentures make a sticky detour in a cinema; a pedagogical disciplinarian (with the apt name of Mrs. Pinch) meets her match; and frozen long-johns defrost by a indoor wood stove. It’s a winning read, guaranteed to make you smile. And who can resist a vignette titled “The Night Her Mother’s Hair Turned White?”

exquisitely evocative B&W photography. Here, she ventures into prose with a collection of short vignettes based on stories her mother told her over a lifetime, starting in Glasgow, Scotland in 1906 and ending in Toronto in 2018. These ostensibly true (though maybe occasionally tall) tales are instantly engaging stuff, infused with a wry sense of humor that’s reminiscent of the work of Ottawa Valley storyteller Mary Cook (who was long a staple on CBC Radio’s “Fresh Air”). There’s a down-to-earth quality to Williams’ unpretentious, ‘what you see is what you get’ cast of characters; and, their experiences, gleaned from the stuff of ordinary everyday life, is often accompanied by closing turns worthy of O. Henry himself. A matter of fact tone belies the gentle irony in accounts which are at once character-specific and effortlessly relatable. An 86-year-old driver navigates off-road mishaps with aplomb; a roller skater meets his fate in the form of a sewer grate; dentures make a sticky detour in a cinema; a pedagogical disciplinarian (with the apt name of Mrs. Pinch) meets her match; and frozen long-johns defrost by a indoor wood stove. It’s a winning read, guaranteed to make you smile. And who can resist a vignette titled “The Night Her Mother’s Hair Turned White?”

Review © 2021 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: Scroll down this page for an exhibition of Pamela Williams’ gorgeous photography, remounted from an earlier feature in the hard-copy edition of Artsforum Magazine. And, for a sampling from “Evelyn’s Stories,” and information on how to purchase it, see: https://artsforum.ca/word/memoirs

***************************

“All the Hidden Truths” (Hodder & Stoughton, 2018): In Claire Askew’s debut novel, a man walks into a college in Edinburgh and kills thirteen women and himself. This psychological drama examines the aftermath of that mass murder. How do people react to senseless crimes of that magnitude? We get the perspective of three different narrators (all of them women): the mother of the killer, the mother of a victim, and a police inspector. The impact of the crime on public at large is filtered through a hysterical social media reaction. The result is a knotty crime novel – and a story of grief. It’s not particularly gory, as its focus is on the repercussions of the mass killing rather than the violent act itself. Alas, its subject-matter is all too relevant to the way our lives in the real world are periodically interrupted with jarring news of precisely such horrific events. The novel won the “Bloody Scotland Scottish Crime Debut of the Year” prize in 2019.

Review © 2020 by Ruth Lafarga.

***************************

“The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance” by Edmund de Waal (Picador, 2011): Edmund de Waal is a wo rld-renowned ceramicist with pieces in major museums. This very personal book is about his family – the Ephrussis, who were as rich as the Rothschilds and made a major impact on Paris and Vienna at the turn of the 19th century. Sadly, by the end of World War Two, their only possession was 264 ‘netsukes’ (miniature utilitarian sculptures from 17th century Japan), which had been acquired by Charles Ephrussis and given to his nephew as a wedding present. Charles made his life a study of art and fine living; but, Hitler’s followers appropriated the rest of the family’s magnificent property. One can’t help but be impressed with the depth of research done for this masterful book. It depicts its characters as real people, its locations as beautifully furnished homes, and its times as rich and challenging. And, it ends with an unexpected twist.

rld-renowned ceramicist with pieces in major museums. This very personal book is about his family – the Ephrussis, who were as rich as the Rothschilds and made a major impact on Paris and Vienna at the turn of the 19th century. Sadly, by the end of World War Two, their only possession was 264 ‘netsukes’ (miniature utilitarian sculptures from 17th century Japan), which had been acquired by Charles Ephrussis and given to his nephew as a wedding present. Charles made his life a study of art and fine living; but, Hitler’s followers appropriated the rest of the family’s magnificent property. One can’t help but be impressed with the depth of research done for this masterful book. It depicts its characters as real people, its locations as beautifully furnished homes, and its times as rich and challenging. And, it ends with an unexpected twist.

Review © 2020 by Ruth Lafarga.

***************************

“The Golden Key: A Victorian Fairy Tale” by George MacDonald, with Illustrations by Ruth Sanderson (Eerdmans, 2016): The Victorian writer George MacDonald (1824-190 5) inspired the estimable likes of Tolkien, Lewis, and L’Engle – all of whom are great luminaries of High Fantasy. In an afterword, the writer Jane Yolen says that “The Golden Key” can be enjoyed as a fairy tale or as “an extended metaphor… about living a life of constant search.” And what a beautiful volume with which to revisit (or discover for the first time) this timeless story (first published in 1860)! The exquisite black & white pen-and-ink drawings by Ruth Sanderson are moody, evocative things of wondrous beauty; described as “scratchboard pictures,” they resemble prints from woodcarvings, and, my goodness, they make it so easy to ‘throw yourself into’ the story, as one of its characters urges.

5) inspired the estimable likes of Tolkien, Lewis, and L’Engle – all of whom are great luminaries of High Fantasy. In an afterword, the writer Jane Yolen says that “The Golden Key” can be enjoyed as a fairy tale or as “an extended metaphor… about living a life of constant search.” And what a beautiful volume with which to revisit (or discover for the first time) this timeless story (first published in 1860)! The exquisite black & white pen-and-ink drawings by Ruth Sanderson are moody, evocative things of wondrous beauty; described as “scratchboard pictures,” they resemble prints from woodcarvings, and, my goodness, they make it so easy to ‘throw yourself into’ the story, as one of its characters urges.

Review © 2018 by John Arkelian.

***************************

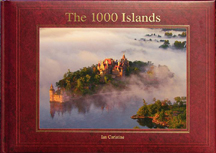

A northerly archipelago can be found in the heart of central Canada,  enticingly presented in the airborne photographs of Ian Coristine’s “The 1000 Islands” – a spellbinding collection of images of “the world’s most beautiful and intricate labyrinth.” Although it is proximate to millions of people in Ontario, Quebec, and New York State, this glacier-made Eden remains an undiscovered treasure for most of us. Coristine’s lovely book (the first of several volumes of aerial photography of the Islands) will instill a yearning to experience this sprawling, magical place (all 200 square miles of it) first-hand. Coristine’s books are available at http://www.1000islandsphotoart.com/books

enticingly presented in the airborne photographs of Ian Coristine’s “The 1000 Islands” – a spellbinding collection of images of “the world’s most beautiful and intricate labyrinth.” Although it is proximate to millions of people in Ontario, Quebec, and New York State, this glacier-made Eden remains an undiscovered treasure for most of us. Coristine’s lovely book (the first of several volumes of aerial photography of the Islands) will instill a yearning to experience this sprawling, magical place (all 200 square miles of it) first-hand. Coristine’s books are available at http://www.1000islandsphotoart.com/books

See Artsforum Magazine’s travel feature on the Thousand Islands, featuring photography by Ian Coristine, at: https://artsforum.ca/travel/other-wanderers

Review © 2018 by John Arkelian.

**************************************************

Finding Solace Among the Dead, Hating Americans, and Slaying Vampires:

108 Books Reviewed in Brief

© By John Arkelian

© Photography by Pamela Williams

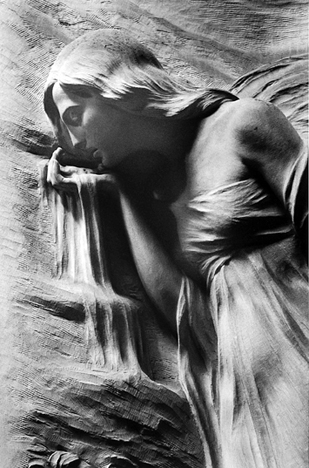

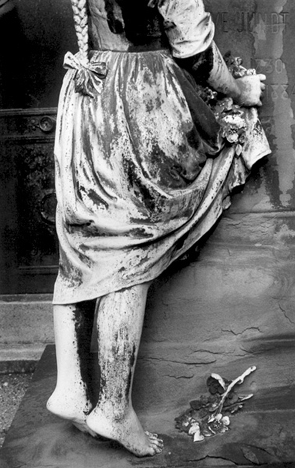

Canadian photographer Pamela Williams has found inspiration for

“Grief” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

her elegant, evocative B&W photography in an unexpected place – the cemetaries of Paris, Rome, Genoa, Milan, and Vienna. There she has found sculptures that evoke moods as varied as the imagination. You will find serenity, repose, sorrow, contemplation, grace, and painful beauty in Williams’ exquisite, flawlessly sensitive images. They are gathered in three slender volumes: “Death Divine” (1995), “Last Kiss” (1999), and “In the Midst of Angels” (2005). There’s something of the immortal here, with human and angelic figures caught unawares in moments in time. These figures are so startlingly life-like, one expects them to awaken at any moment. Are these images melancholy? Perhaps a little. But the figures they depict both commemorate and celebrate life. Indeed, many of these stone figures are redolent of life and hope – like the picture dubbed “White Woman,” in which a young woman’s face is positively alight with exuberant vitality. There’s something in these

“Siren” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

collected pictures that speaks of the slumber that people of faith believe prefigures our awakening to life abundant – the dream that comes before the true and lasting dawn. Williams’ photographs are as eclectic as they are dreamily romantic: Here a women cups her hand to capture a falling cascade of water; there a pensive nymph rests half-emerged from her elemental home; elsewhere a woman sits lost in thought with eyes closed and head resting against an open palm; while somewhere else two hands rest on a flat surface with fingers meeting to frame a triangle of empty space – space, maybe, that represents the unknowable hereafter or the finite span each of us passes on this Earth. Pamela Williams’ breathtaking work is available though: http://www.interlog.com/~romantic/

The title says it all in “Evocations of Place: The Photography

“Cameo” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

of Edwin Smith,” edited by Robert Elwall (Merrell/RIBA Trust, 2007). A preeminent British photographer, Smith (1912 – 1971) was equivocal about his vocation, declaring that he was “an architect by training, a painter by inclination, and a photographer by necessity.” Yet his B&W photographs of architecture and landscapes alike are lyrically compelling. Much of Smith’s work depicts his native England, with pictures of the rolling West Yorkshire landscape, a rocky Dorset shore with headlands in the distance, a sparsely peopled Brighton beach under a glowering sky, and the interiors of stately homes that will make you swoon with pleasure. Beautifully

“Divine” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

composed and impeccably lit, these images evoke the very soul of what they depict. It’s too bad, as the editor points out, that “Smith’s gentle, probing imagery has recently fallen victim to a changed photographic taste that values visceral shock over subtle resonance.”

Yet subtlety and resonance endure, even in the field of modern photo-journalism. Witness “Forsaken” by the award-winning Canadian photographer Lana Slezic (Anansi, 2007). A riveting, indispensable look at the lives of women and girls in post-Taliban Afghanistan, the book is enough to make the reader cringe. Gender-based inequality, oppression, and abuse remain as endemic as ever in the country we helped ‘liberate.’ There’s sixteen year old

“Roman Angel” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

Samia, for example, obliged to abandon her cherished education as a result of a forced marriage: “She was a radiant teenager who in any Western country would be sitting at a school desk. Instead, from that day forward, at the request [read insistence] of her husband, she would wear a burka in public and live according to the rules set out by him and his family. In many ways, life for Samia as she knew it had come to an end.” And what of Shaima, an educated, liberal, 24-year old woman who had attained a remarkable degree of independence as the host of a local television show (and whose sister represented their country in judo at the 2004 Olympics)? Her promising life was cut short, when she was murdered by her brothers – a so-called “honor killing” prompted by the offense of

“Cyprus” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

having a boyfriend. Another girl, eleven-year old Gulsima, bears the scars of the savage beatings she endued after her forced marriage and enslavement at the age of four. Slezic’s color photographs are poignant studies in injustice and human endurance. They speak volumes, shattering illusions about the changes many of us assume have accompanied Western intervention in Afghanistan. Is this the best we can do in that poor benighted place? If it is, then our brave soldiers (and aid workers) are dying in vain.

Sometimes photography is just about celebrating beauty – in all its manifold forms. “Shells” by Paul Starosta (Firefly Books, 2007) is just such a celebration – in coffee table book proportions – of the kaleidoscopic variety of colors, shapes, and textures of sea shells.

“Sorrow” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

From sleek swirls that conjure unicorns to elephantine curls to smooth curves that look almost erotic, that variety is infinite. Can a mollusk shell constitute “art?” Assuredly yes, if the pleasure to be derived from these pages is any guide. Sensual curves are also prominent in “Nude Photography: The Art and the Craft” by Pascal Baetens (DK Publishing, 2007). That Belgian photographer covers all of the elements of a good photograph – from lighting and composition to perspective and locations (“look for what is beautiful, even if it is only a tiny part of a place”). Instructive, and mighty nice for browsing, the book devotes its last 100 pages (out of 250) to a portfolio of work by ten photographers, with detailed dissection and analysis of each picture. For its part, Richard Kern’s “Looker”

“Dreamer” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

(Abrams, 2008) is a playful pretense at carefree voyeurism (rather than the scary, stalking variety) as the photographer catches casual glimpses of his models at rest and play. The result is no more than mildly interesting, and it does not need the undignified endcovers, which suggest something less innocent. Fellow autumn-people will be captivated by “A New England Autumn” by Ferenc Mate (Albatross Books/Norton, 2007). Three parts photography and one part travel guide, with a sampling of writings by New England writers ranging from Emily Dickinson to Robert Frost and from Longfellow to Thoreau, the book will enthrall with its images of crimson and yellow foliage, whispering waterfalls, mist-covered lakes at sunrise, and red skies over quiet harbors at dusk. One can

“Lament” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

almost feel the bracing caress of the brisk fall air, inhale the hint of smoke from distant fireplaces, feel the spray of the surf, and get lost in dreams of resplendent woods ablaze in color. And the book’s brief tour-planner is a good place to get started if a first-hand excursion to New England beckons.

Whoever said a picture is worth a thousand words must have had “100 Days in Photographs,” edited by Nick Yapp (National Geographic 2007), in mind. Gleaned from the archives of Getty Images, these pivotal pictures represent landmarks in our history, from the mid-19th century to the devastation wrought upon New Orleans in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina. These are unforgettable moments, caught in classic still photographs – of the London Blitz,

“Niche” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

the landings on D-Day, the awful destructive power of the first atomic bombs, cultural icons like Elvis Presley and the Beatles, the funeral of President Kennedy with his three-year old son saluting his coffin, Man’s first footprints on the surface of another world in July 1969, the ignominious fall of Saigon in 1975, the celebratory fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the horror of 9/11. Each event is narrated by a short text, and the result is a fascinating chronicle of our age – a treat both visually and historically.

There’s more than one way to explore history. Witness “Old Canadian Cemetaries: Places of Memory” by Jane Irwin with photographs by John de Visser (Firefly Books, 2007) which canvasses burial traditions among the various peoples (Quakers,

“Longing” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

Jews, Anglicans, and African-Americans, among them) who make up Canada, as well as war memorials, the interpretation of tombstone symbols, and more, while citing Stephen Leacock’s remark that “the old grave that stood among the brambles at the foot of our farm was history.” Burying grounds not only contain generations past, their headstones are also genealogical treasure troves, while the landscape architecture of some of the best sites are living legacies as fine arboretums. Brock’s Monument is here, towering above the 1812 battlefield of Queenston Heights. So too, is the Inuit Memorial in Hamilton, erected to commemorate the Inuit people decimated by tuberculosis: Between 1952 and 1963, many of them were treated, far from home, in Hamilton, where some succumbed, without their

“Triangle” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

families ever being notified. The pages of this book depict places of memory, reflection and beauty – and the result is a fascinating excursion into history that is at once very personal and shared.

The appreciation and conservation of our natural heritage is the subject of three books about different parts of the British Isles. Produced in association with the Campaign to Protect Rural England (http://www.cpre.org.uk/), “A Portrait of England,” edited by Joanna Eede (Think Books/Sterling, 2006), combines glorious photographic vistas of undulating green hills, tranquil farmland, and rugged moors with three dozen short essays on everything from sustainability to ‘the meaning of trees:’ “I’ve never been able to shake off the conviction that the only way to pay rent

“Light” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

for one’s time on Earth is to leave it in a better state then it was when one arrived.” Like novelist, and contributor, Margaret Drabble, you’ll feel that “no one has ever seen this world before.” Not to be outdone, Britain’s National Trust has published two volumes of wonderful images gleaned from a photographic tour of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland: “Coast” (1998/2006) and “Countryside” (1998/2006) are both collaborations between Joe Cornish, Paul Wakefield, and David Noton. And, the fruits of their labors are a joy to behold, with breathtaking images, like the granite islet of Lundy, the colored sands of Alum Bay on the Isle of Wight, the unspoiled sand dunes of Formby Point near Liverpool, the circular Mussenden Temple perched atop a cliff in Londonderry, the sea-cliffs of Stackpole in Pembrokeshire, ancient pollard trees in Hertfordshire that look like something out of Middle-earth, and the three-counties-spanning Peak District, with its panoramic views of the inimitable green English countryside. The images in these wonderful books are irresistible – the stuff of soulful longing. Speaking of places that speak to the soul, our very own Cape Breton

“Water” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

Island is just such a place. One of its most talented photographers, Warren Gordon, has another book that captures the charm, conviviality and natural beauty of the place. “Baddeck: Heart of Cape Breton” (Nimbus, 2006) is a tribute to the small town that serves as embarkation point for the Cabot Trail and a tourist destination in its own right, thanks to its proximity to the Bras d’Or inland sea, its famous adopted son Alexander Graham Bell, and its marvelous small-town hospitality. The result is a necessary keep-sake for everyone who knows and loves the place. Now, if only Gordon will turn his camera lens northwards to the wonderful Middle Head Peninsula and Ingonish for his next book!

We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: National Geographic’s Traveler series are comprehensive, informative, well-organized, and visually appealing – a whole world of information (about cities, regions, and whole countries) between two covers. If Italy beckons, there are new guides on “Rome” (2nd ed., 2006), “Naples & Southern Italy” (2007), and “Florence & Tuscany” (2nd ed., 2006). The first book covers everything from the Via Veneto’s

“Flower” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

dining possibilities to the Vatican’s center of things ecclesiastical, with stops for the Trevi Fountain, the Pantheon, and the Colosseum. The second volume will tempt with its enchanting Amalfi coast and isle of Capri, not to mention the excavations at Herculaneum (one of two towns that incurred the volcanic wrath of nearby Vesuvius in 79 A.D.), the region’s rich offerings in music, art, and cinema, and the newly popular Calabrian Riviera. The third volume takes us north of Rome to see sculptures by Michelangelo, Botticelli’s Venus, and the rest of the region’s endlessly rich cultural heritage. (One error: a photograph from the 2003 film Under the Tuscan Sun actually shows Positano on the far-off Amalfi coast.) And that’s not even mentioning the vineyards and olive trees of the Tuscan countryside. If you set out across the Ionian Sea (and you’d be remiss not to) the volume on “Greece” (2nd ed., 2007) will guide you through that country’s innumerable classical ruins. Athens’ Acropolis, its Plaka, and its highest hill, “Lykavittos,” which is accessible by funicular railroad and affords a magnificent view of the city by night. And speaking of magnificence, don’t forget the Greek Isles, set, as they are, in a turquoise sea and adorned with white-washed habitations. For travelers destined for northwestern Europe, volumes on “France” (2nd ed., 2007), “Germany” (2nd ed., 2007), “Berlin” (2006), “Great Britain” (2nd ed., 2007), and “Ireland” (2nd ed., 2007) will dazzle with their driving and walking tours, insights into local customs, tips on food and drink, first-rate maps, and comprehensive coverage of everything to see and do in both town and country. Among the attractions: the chateaux of the Loire Valley, the romanticism of Schloss Neushwanstein atop an Alpine crag, remnants of the Berlin Wall, the apotheosis of academe that is Oxford, and the 665-foot cliffs of Moher on Galway Bay. Closer to home, the volumes on “New York” (2nd ed., 2006) and “Canada” (2nd ed., 2006) offer guidance on such things as a metropolis’ museums and the awesome diversity of the world’ second-largest country.

Speaking of which, “Unforgettable Canada: 100 Destinations” by George Fischer & Noel Hudson (Boston Mills Press, 2007) is a sheer delight. Gorgeously illustrated with color photographs, it devotes two to four pages each to such diverse and breathtakingly wondrous places as Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland,

“Herald” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

Saskatchewan’s Great Sand Hills, B.C.’s Inside Passage, and Cape Breton’s Cabot Trail. It’s a must-have book about must-see places, and it’s guaranteed to quicken your pulse. In a similar spirit, “Guide to Scenic Highways & Byways: The 275 Best Drives in the U.S.” (National Geographic, 3rd ed., 2007) is less of a picture book and more of a guide book. But the places to which it will guide you – like Oregon’s Pacific Coast Scenic Byway, the lunar landscape of South Dakota’s Badlands, and the autumn wonderland of New Hampshire and Vermont – are nothing short of magical. And, if you want to linger in the northeast, you’ll want to see “Weekends for Two in New England: 50 Romantic Getaways” by Bill Gleeson & Cary Hazlegrove (Chronicle Books, 2nd ed., 2006). The inns it depicts, across six states, aren’t for bargain-hunters; but they most decidedly are for everyone who craves a haven of elegance, beauty, and utter romanticism. If the whole world is your oyster, “Journeys of a Lifetime: 500 of the World’s Greatest Trips” (National Geographic, 2007) will take you everywhere from the gardens of England to an Alpine balloon festival over Switzerland and from a pub crawl Down Under to a floatplane tour over Canada’s Nahani National Park. The book is arranged according to mode of travel (by water, road, rail, air, and foot) and by the objective of that travel – be it cultural (like Kabuki theater in Japan), palate-preoccupied (like California’s Napa Valley wineries), or action-oriented (like horseback riding on the Santa Fe Trail or rafting through the Grand Canyon). In short, there’s something for everyone between these covers. And, while you’re en route from Point A to Point B, what better way to occupy yourself than with the keen-eyed and witty observations of “Touché: A French Woman’s Take on the English” by Agnes Catherine Poirier (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006). The author touches on everything from Europhobia to pets: “The Brits love animals to the point of turning into vegan terrorists, whereas the French love animals so much they simply… eat them. Same feeling, different application.” Reflecting upon the conundrum of a nation that’s home to both the best (think BBC) and worst (think the “cheap and nasty” tabloids) in journalism, Poirier notes wryly that while “a French journalist is

“Nymph” – copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams

more an editorialist… British journalists by contrast are sleuths. They never take themselves too seriously; there is a job to be done, and it will be done, thoroughly.” And in the realm of fine cinema, serious cinephiles in Britain “have to hide, like the early Christians in pagan Rome.” Poirier’s writing is casually elegant and her observations of all things English are as affectionate as they are astute.

Devotees of all things Klimtian have cause to celebrate, with Prestel’s recent release of four new books about the Viennese painter. Pride of place must go to the over-sized, slip-case covered magnum opus titled simply “Gustav Klimt,” edited by Alfred Weidinger (Prestel, 2007). You’ll need a sturdy coffee table to support the monumental dimensions (and weight) of this compendium of all 253 of the artist’s paintings; but, this is one book for which it’s worth making room. Gloriously illustrated and insightfully written, this comprehensive catalogue of Klimt’s work truly achieves its goal of reflecting the beauty of the paintings. The result is indispensable for serious students of Klimt. Readers looking for an introductory approach will find it in Nina Kransel’s compact volume “Gustav Klimt” (Prestel, 2007), which gives an accessibly written, handsomely illustrated overview of the artist and his work. One specific piece of his work is the focus of attention in “Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze and the Controversy over the Freedom of Art,” edited by Stephan Koja (Prestel, 2006). It certainly got attention in 1902! One unimpressed critic decried it as depicting “the nastiest females I have ever seen… Klimt dreamt them up to enrage us. In my mind, I quietly calculated how many millions these women would need in dowries to find husbands…” The series of connected scenes, painted directly on the plaster walls of the Secession exhibition building, were intended as a symbolic and highly personal interpretation of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, but they fell afoul of prevailing notions about good taste and the acceptable uses of symbolism. Young readers will get a colorful introduction to the artist in “Gustav Klimt: A Painted Fairy Tale” by Stephen Koja (Prestel, 2007).

Closer to home, “Canadian Paintings, Prints and Drawings” by Anne Newlands (Firefly Books, 2007) surveys 164 artists from across four centuries of Canadian history. Each gets equal space – with a page of text and a single example of their art on a second page – and all were selected with a view to displaying ethnic and regional diversity as well as thematic eclecticism. There are portraits and landscapes, as well as classical, aboriginal, and abstract techniques represented here. Among the standouts are George Theodore Berthon’s “The Three Robinson Sisters” (1846) with its trio of finely-attired young ladies from Toronto’s upper class; a dramatic B&W etching by David Blackwood of a long-boat towing a house off the coast of Newfoundland; Miller Brittain’s 1940 Brughelesque depiction of a rummage sale; Emily Carr’s majestic “Red Cedar” (1931); Alex Colville’s ominous 1954 painting of a black horse galloping toward an oncoming train at dusk; Clarence Gagnon’s idealized 1927 vision of a Laurentian village in winter; and Lawren S. Harris’ striking and stylized 1928 “Lake and Mountain,” to name but a few. The result is a fine encyclopedic primer on the history of Canadian two-dimensional art. Art from a very particular cultural perspective and place figures in “Cape Dorset Prints: A Retrospective,” edited by Leslie Boyd Ryan (Promegranate, 2007). The Inuit cooperative formed at the Baffin Island hamlet in 1959 has become an acclaimed source of prints. Depicting human society and the natural world of the north, the resulting stonecuts, linecuts, engravings, etchings, lithographs, and other media range from folk art to refined art in styles that cover the gamut from the fanciful and impressionistic to the realistically lifelike and on to the symbolic and stylized. But they are always distinctively imaginative and keenly attuned to the natural world – of caribou, killer whales, ravens, owls – and man’s place in it. Essays by a dozen participants from the Kinngait Studios give a fascinating account of this microcosmic society within a society.

“Beasts: Factual & Fantastic” by Elizabeth Morrison (Getty, 2007) is the first in a planned series of books using illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages and early Renaissance to explore a theme. First up are animals – from the mundane and domesticated to the exotic and on to the purely fanciful. You’ll find farm animals and hunting dogs in these colorful pages as well as dragons and ‘hybrids’ comprised of parts from multiple animals (sometimes including man). On the metaphorical end of this fascinating volume’s bestiary spectrum you’ll find the various dragons, locusts, and martial horsemen who constitute the dramatis personae of the Apocalypse. The same publisher also offers a new volume in their separate “Guide to Imagery Series:” “Gardens in Art” by Lucia Impelluso (Getty, 2007) looks at different kinds of gardens and their constituent elements – like trees, benches, urns, labyrinths, and water-features. Well-nigh every page has a color illustration – gleaned from 400 works of art – and each is analyzed for what it says about the customs or beliefs of the societies that created these gardens.

Combining artistic self-expression, anthropology, and down-to-earth meditations on the human condition, “Learning to Love You More,” edited by Harrell Fletcher & Miranda July (Prestel, 2007) fascinates with its minutiae from the lives of strangers. Based on a project which invited visitors to a website to complete an assignment and post it online, it offers glimpses into other lives which are astonishingly intimate, touching, and familiar. Examples of these assignments were to write the phone call you wish you could have made (perhaps to an estranged or lost loved one); photograph a significant outfit (one respondent submitted a picture of clothes “I wore [on] the day I lost my virginity to a guy who hurt me pretty badly in the end. That’s life. But I still miss him.”); take a flash photo under your bed (monsters may not lurk there, but any manner of other flora and fauna do – from pet bunnies to dust bunnies); interview someone who has experienced war; ask your family to describe what you do; and so on. The result is tender, poignant, and surprisingly compelling.

Self-expression also figures prominently in “Hand Job: A Catalog of Type,” edited by Michael Perry (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007). Celebrating the brave few typographers who still work by hand, the book is a marriage between free-form creativity and the doodle, with an illicit liaison with graffiti on the side. To draw type by hand is to “start at zero and add; everything is a decision to be made” and a lesson to be learned. To forego a computer in favor of hand and pen is to “work on a micro scale… How am I going to space this?… Why can’t I draw today? All defaults are gone. It’s me versus the world; even when I lose, at least it’s an interesting place to be.” Then there’s “The Guerilla Art Kit” by Keri Smith (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), which has as its aim the promotion of hand-made public art, art that affirms the presence of the human spirit and advocates for change: Guerilla Art is “about leaving your mark.” It provides recipes for whimsy – like leaving a trail of words (or quotations) with post-it notes; offering free lessons in starting a conversation with a stranger; attaching blank tags (and instructions) on a “wish tree;” decorating a chain link fince with found objects; knitting garlands for street signposts; leaving a book in a public place; and planting flower seeds on neglected urban lots. The idea of such street art is to connect with our environment and with each other.

Speaking of whimsy, you’ll find oodles of it in “Sublime Spaces & Visionary Worlds; Built Environments of Vernacular Artists,” edited by Leslie Umberger (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007), which served as a catalogue for an exhibition last year at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. It features the work of 22 decidedly non-traditional artists who converted their homes into large-scale expressions of their unique visions. Some are wonderful (like Levi Fisher Ames’ carved miniature animals displayed in shadow-boxes); some are strange (like Sam Rodia’s intricate spiral towers, made of concrete embellished with shells and colored glass and looking like the skeletons of some unknown ocean-dwelling leviathans); and some may be the products of madness (like Emery Blogdon’s labryrinthine ‘Healing Machine’ – a fantastical concoction of wire, foil, wood and magnets. And that’s not even mentioning a rhinestone room, books crafted from glass and resin, and delicate thrones made from chicken bones. Creativity runs riot here, in a place where inventiveness re-defines the idiosyncratic and brilliance defies conventional ways of seeing the world. Defying convention is also the stock in trade of “Erotic Comics: A Graphic History from Tijuana Bibles to Undergound Comix” by Tim Pilcher (Abrams, 2008). Such erotica for the masses has run the gamut from the gently coquettish to the overtly lascivious. But whether it took coarse or refined forms, its object was to titillate, and it employed astounding inventiveness in situation and style to do just that. So, proceed with caution here: There’s bound to be as much to offend as to arouse in these pages.

Whoever said that a picture is worth a thousand words must have had “Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels,” edited by George A. Walker (Firefly Books, 2007) in mind. These wordless novels by four of the world’s greatest woodcut artists are powerfully compelling – both in their sheer visual impact and in the universal resonance of the stories they tell. They tell of injustice, oppression, and despair, but also of defiant endurance and the dream of a better world. Their striking B&W images are full of meaning and emotion, making this one of the most elegantly engrossing books of recent months. Rush out and buy it, for it is not to be missed! Nearly as good is “Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels,” edited by David A. Berona (Abrams, 2008). Gathering excerpts from many of the major woodcut novels from 1918 to 1951, its “arresting and iconic” art illuminates “the darkest corners of the human experience,” with a remarkable (and timeless) pathos for the human condition.

The contemporary novelist Audrey Niffenegger has tried her hand at the near-wordless form with two recent books: “The Three Incestuous Sisters” (Abrams, 2005) and “The Adventuress” (Abrams, 2006). The former’s tale of three sisters who live alone by the sea until a young man named Paris (his name and the choice he has to make are playful allusions to Greek mythology) enters their lives. Romance, jealousy, and tragedy ensue, leavened by a measure of redemption. In the second book, a young woman created by an alchemist is forceably carried off by a rich man and kills him, later finding true love and losing it due to the man’s faithlessness. Both stories have elements of fantasy; but they’re anchored in real-life desire, loss, pain, and regret. And they have a delicacy and poignancy that captivates.

Though not completely wordless, “The Hapless Child” by Edward Gorey (Pomegranate, 1961/1989) gleans its ruthlessly dark impact from Gorey’s Gothic pen-and-ink drawings and their gleefully malicious depiction of the unhappy misfortunes that befall its hapless young heroine. The delicate gentility of Gorey’s inimitable art belies the calamitous nature of the events it depicts. In “The Twelve Terrors of Christmas” (Pomegranate, 1993/2006), Gorey’s mournful characters populate novelist John Updike’s irreverent musings about everyone’s favorite season: On the Christmas tree, he wonders, “suppose it topples over under its weight of bomb-shaped baubles?” As for Santa’s helpers, he wonders if “the rat-a-tat-tat of tiny hammers” may prefigure an eventual rebellion of this oppressed underclass of diminutive shop-workers. As to the store windows “full of styrofoam snow… [and] mannequins posed with false jauntiness in plaid bathrobes,” this little (and darkly funny) book asks us to consider, “Is this Hell, or just an upturn in consumer confidence?”

There’s nothing funny about “Ashen Sky: The Letters of Pliny the Younger on the Eruption of Vesuvius” (Getty, 2007); but there’s much that’s striking and immediate, due, respectively to Barry Moser’s wonderfully dramatic B&W wood engravings and the first-person account (written in 79 A.D.) of a Roman eye-witness to the cataclysm: “There were some who in their fear of dying begged for death; many raised their hands to the gods; still more concluded that there were no gods left and that harsh and everlasting night had descended on the world.”

Self-absorbed twenty-somethings figure prominently in comic-book artist Adrian Tomine’s pictorial novella “Shortcomings“ (Drawn & Quarterly, 2007). Its leading figure is an Asian-American man who spends a lot of time feeling sorry for himself and projecting barrages of cynicism and sarcasm. He’s a self-made “loser,” but he’s got one true friend and enough flawed humanity to garner our sporadic sympathy. What rings truest here are the relationships, even if these characters aren’t always likeable. While that book is suitable only for mature readers, two others will charm all ages: “My Travels with Clara” by Mary Taverner Holmes, with illustrations by Jon Cannell (Getty, 2007) is a sweetly whimsical account of an Indian rhinoceros named Clara who was adopted by a Dutch sea captain in the 1730’s and treated to a tour of Europe’s great cities. Royalty came to see her, and her exotic features inspired artists to capture her likeness in porcelain, bronze, and oil portraits. We learn that this down-to-earth celebrity “could never get enough oranges [or beer] and had a soft tongue, like a puppy’s.” The story has the fanciful allure of a fable, but it’s a true story – one that elicits a sense of real fondness for its heroine. For its part, “Mrs. Marlowe’s Mice” by Frank & Devin Asch (Kids Can Press, 2007) is a gorgeous imagining of a world peopled by anthropomorphic cats and mice. It’s a feline-dominated society in which “harboring mice” is a crime; but one kind librarian defies the authorities by befriending an extended family of mice. Meant for ages five to nine, this ingeniously imagined, exquisitely illustrated book will enchant readers of all ages. The same goes for “Greece in Spectacular Cross-Section” by Stephen Biesty (Oxford U. Press, 2006). Set in 436 B.C., it charts the journey of two boys and their father from the city of Miletus to the athletic games in Olympia by way of the great city of Athens. Like earlier volumes on Rome and Egypt, the book’s stock-in-trade is its incredibly detailed drawings of homes, shops, temples, theaters, and city-scapes – all presented in cross-sections, cut-aways, and panoramic views on its large pages. The result is guaranteed to fascinate readers young and old for hours on end.

At its best, cinematic popular culture can attain the level of art, sometimes drawing on other media for its inspiration. That’s the idea behind “Once Upon a Time: Walt Disney – The Sources of Inspiration for the Disney Studios,” edited by Bruno Girveau (Prestel, 2006), which was published in conjunction with a major exhibition in Paris and Montreal. It takes as its subject the animated feature films produced under Walt Disney’s personal supervision, from 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs to 1966’s The Jungle Book. One of the reasons those films have such an enduring appeal is the myriad of connections they have to artistic, literary, musical, and cinematic sources. The result was a re-imagining of iconic images and themes – images and themes which continue to hold great resonance for the viewer: “Disney absorbed the past and the Old World and reclaimed them for a new and still vibrant culture… At their best, [his] films universalize human experience, both ‘vulgar’ in the old-fashioned sense ‘of the people,’ and profound.” Full of insights and lavishly illustrated, this smart, handsome book will inform and delight readers.

Film buffs won’t want to miss “501 Movie Stars“ or “501 Movie Directors,” both of which are edited by Steven Jay Schneider (Barron’s, 2007). The former devotes one or two (and occasionally as many as four) pages to the actors it canvasses, presenting them in chronological order, from the 1860’s to present. Each entry succintly captures the essence of their work, their lives, and their cinematic appeal. We learn that Cary Grant turned down the roles of James Bond in Dr. No, Humbert Humbert in Lolita, and Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. About Orson Welles, we’re told that his career “is a test case for artistic integrity run aground against the demands of a cut-throat business.” Inevitably, some inclusions (Divine!) and omissions (William Powell, Barbara Stanwyck, Tom Wilkinson, and Emmanuelle Beart) will puzzle; but the book is as entertaining as it is informative. That goes for the director’s volume, too – even if it dares to compare the maven of heavy-handedness, Brian De Palma, with Alfred Hitchcock, and lets George Lucas off the hook entirely for his shamelessly foisting empty “blockbusters” upon modern audiences. But opinions aren’t lacking in “101 Movies to Avoid” by Allan Smithee (Cyan, 2006). Writing under a pseudonym, the author (who is a film publicist in real life) decries as overrated such films as Titanic (“a tragedy for cinema” that provided a handy outlet for audience tears in the aftermath of Princess Diana’s death); West Side Story (with “two of the lamest gangs ever seen”); and Scent of a Woman (“Once upon a time Al Pacino was a very talented actor… and then he began shouting”). No need to ask the author what he/she really thinks; this is one book that makes no apologies for being utterly subjective. Whether you agree with its author’s pronouncements or not (Anthony Hopkins “got lucky once… and has fooled people ever since”), they’re delivered with gusto and make for amusing reading. More “refined” film criticism can be found in “American Movie Critics,” edited by Phillip Lopate (Library of America, 2006/2008), which offers an anthology of film criticism from 71 writers. Spanning over 80 years, we get thoughtful analysis – of particular films and directors – and essays, like Pauline Kael’s thoughts on “Trash, Art, and the Movies:” “When you’re young the odds are very good that you’ll find something to enjoy in almost any movie. But as you grow more experienced, the odds change… The problem with a popular art form is that those who want something more are in a hopeless minority compared with the millions who are always seeing it for the first time, or for the reassurance and gratification of seeing the conventions fulfilled again.” Writing about film can be smart and elegant, and this book is the proof.

Several new film (or television) related books deal with very specific topics: “Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Making of Steven Spielberg’s Classic Film” by Roy Morton (Applause, 2007) is a thorough, and thoroughly engaging look at the production of a single motion picture. “Film Festival Confidential” by William Marshall (McArthur & Co., 2005) is a plainspoken, first-person account of Toronto’s biggest film festival by one of its founders; and it is chatty and opinionated: “We were the only three people with the brains, and balls, and the bulldog grip to get it done.” William Beard’s “The Artist as Monster” (U. of Toronto Press, revised ed., 2006) is a scholarly interpretation of the films of Canadian director David Cronenberg, up to his 2002 film, Spider. The result will suit academic readers and serious students of film better than general readers. For its part, “On Location: Canada’s Television Industry in a Global Market” by Serra Tinic, (U. of Toronto Press, 2005) is best appreciated by academic readers, with themes like Canadian television comedy’s tendency to strike out at authority, with ambivalent irony, from places that are, geographically or otherwise, marginalized (e.g. the Maritimes-based This Hour Has 22 Minutes). And, there’s a look at the life of Canada’s most articulate, urbane, and impeccably well-prepared interviewer of film personalities in George Anthony’s “Starring Brian Linehan” (McClelland & Stewart, 2007). The biography is an engagingly-written account of one of Canada’s leading media interviewers in the 70’s and 80’s; but, whether a man best known for listening merits a book-length biography, is anyone’s guess.

“The Spider-Man Chronicles” by Grant Curtis (Chronicle Books, 2007) is an insider’s look at Spider-Man 3, from story development (its hero has to learn humility) to designing the costumes, visual effects, and over-all look of the film. And it is generously illustrated with concept art, models, and behind the scenes photographs. The production journal (the author was a producer on the film) that takes up nearly half the book may be too full of gratuitous small details, however; just as the film itself lost its way in a surfeit of plot incidents and effects. “The Art of Beowulf” by Mark Cotta Vaz & Steve Starkey (Chronicle Books, 2007) is better, dispensing with textual minutiae in favor of a trove of character sketches, set and costume designs, and paintings that depict scenes from the film. Those images follow the chronology of the story as they illustrate the meanings meant to be conveyed by the look of the film. For its part, “Stardust: The Visual Companion” by Stephen Jones (Titan Books, 2007) is an attractive look at a story about a star who falls to Earth and takes human form – in a world with witches, dancing sky pirates, and a young mortal man whose shyness turns into heroism. Interviews, costume designs, and the complete screenplay accompany a constellation full of stills from the film – with appealing results.

Elegant design and lavish illustrations are also the hallmarks of Volumes One (2006) and Two (2007) of “Firefly: The Official Companion“ (Titan Books). Noted for his strong characterization and flippant dialogue, television’s Joss Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel) brought both qualities to bear in the short-lived amalgam of sci-fi and western conventions known as Firefly. Only fourteen episodes were made before the series’ premature cancellation, but they found an enthusiastic audience (posthumously, as it were) when they were released on DVD. These two volumes have the complete shooting scripts for all of the episodes, an abundance of stills from the program, insights into everything from character development to the use of music, and close-up photos of the myriad of props used in the show – from weapons to paper money to sets and costumes. The result is two beautifully-produced volumes which are musts for every devotee of the Whedon-verse. Less visually compelling, but no less necessary for its fans, are “Battlestar Galactica: The Official Companion’s” volumes on Season One, Two, and Three by David Bassom (Titan Books, 2005, 2006, and 2007, respectively). With smaller page size, fewer photographs (most of which are in B&W), and a non-glossy format, the emphasis of these volumes is not visual. But the detailed episode summaries and character overviews make them indispensable for this on-going television drama – a drama that’s less about science fiction that it is about human conflict. Similarly formatted, “Stargate SG-1: The Illustrated Companion (Seasons 1 and 2)” by Thomasina Gibson (Titan Books, 2001) performs the same service for the first two (out of ten) seasons of the successful sci-fi/adventure series, with additional sections on production design and visual effects. But “Stargate SG-1: The Ultimate Visual Guide” by Kathleen Ritter (DK Publishing, 2006) lives up to its title as the definitive color cornucopia of the characters, villains, places, technologies, and plot-lines of the series. There’s everything you need to sort out your Goa’uld system-lords, the gutteral language of the Unas, planets like Abydos and Chulak, and allies like the Asgard, Nox, Tokra, and Tollans. It’s chock full of photographs, charts, and design drawings – and it has an 18-minute DVD as a bonus.

Readers with a lingering fondness for the wit, drama, and elegant characterization of television’s now slain Buffy the Vampire Slayer will appreciate two thoughtful books about the series. With a doctorate in religion from Columbia University, Jana Riess explores the ethical and spiritual dimensions of the series’ ethos in her book “What Would Buffy Do? The Vampire Slayer as Spiritual Guide” (Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2004). Its topics include self-sacrifice, confronting our own inner darkness, redemption, and the power of friendship. The series had a sophisticated way of incorporating such ideas into good story-telling. Like its source material, the book is smart and engaging, as it combines accessibility with moral complexity: “On Buffy redemption is never a sure thing, and it’s not a one-time act that guarantees a happily-ever-after future.” For its part, “Why Buffy Matters” by Rhonda Wilcox (I.B. Tauris, 2005) plumbs the depths of meaning in a television series which the author, who is a professor of literature at an American university, defends as “art, and art of the highest order.” She argues that television and aesthetics need not be inherently contradictory. At its best, in a special series like Buffy, it can be art: “It is a work of literature, of language… of visual art… of music and sound… The depth of the characters, the truth of the stories, the profundity of the themes, and their precise incarnation in language, sound, and image – all of these matter. Last and first of all, Buffy matters for the same reason that all art matters – because it shows us the best of what it means to be human.” Love, laughter, fear, poetry, and death figure among the themes of this compellingly written book. It’s a must-have for fans and students of pop culture alike – easily sophisticated enough for scholarly purposes but accessible to a general readership. And, from our ‘next best thing to being there’ department come the first two in a series of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” graphic novels from Dark Horse Books. The television series lasted for seven seasons. Now, it has been reincarnated, in a different medium, for an eighth. Indeed, series creator Joss Whedon personally wrote the first volume, “The Long Way Home” (2007) and it’s got the same snappy wit, offbeat tone, and right-on-the-mark characterization of the television series: Buffy, Xander, and Willow are recognizably themselves – and it’s not just a matter of Georges Jeanty’s remarkable illustrations. No, these characters sound and act the way they should. That goes for the return of series’ baddies Amy and Warren, too: They’re used to ghoulishly frightening effect here. The second volume, “No Future for You” (2008), does equally persuasive work with the series’ recurring bad-girl slayer Faith, though Whedon delegated writing duties for this installment to someone else. But, new characters, introduced for the first time in these graphic novels, are far less compelling than those reprised from the television series. Indeed, some, like a half-mad British aristocrat-brat (who’s more an amalgam of cliches and half-baked ideas of what an English girl might sound like than the genuine article) and her run-of-the-mill warlock tutor, fail to inspire much interest. Luckily, though, the key players are those we know from the television series, and they’re enough to set fans running out to get these (and future) volumes.

A new series of books summarizes the year’s offerings on prime-time American television, from new to continuing series. “TV Year, Volume I” by John Kenneth Muir (Applause, 2007) covers the 2005-06 season and combines a description of each series with a commentary on its strengths and weaknesses. The result is entertaining and insightful. About Supernatural, for instance, the author correctly notes that “for a show meant to blend Route 66 with The X-Files, there is no actual sense of ‘the road.’ ” Equally lacking are atmosphere, a world view that juxtaposes belief and science, curiosity about the bad-guys, and “the emotional depths and extraordinary storytelling of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Angel.” The book similarly uncovers the truth at the heart of Lost’s hype about its own ‘specialness’ by explaining how that series routinely loses its own sense of internal reality and abruptly switches its premises from week to week. Frank Borzellieri’s slender, 90-page volume “The Physics of Dark Shadows” (Cultural Studies Press, 2008) is strictly for fans of the 1966-71 Gothic television drama. “Physics” here is interpreted rather broadly, with sections on such diverse topics as time travel, telepathy, clairvoyance, seances, possession, ghosts, and hypnotism. There’s even a detour to address the fact and (mostly) fiction behind the Amityville Horror yarn. Much of this material has nothing to do with physics; and some of it has little to do with Dark Shadows. Still, as speculative light reading, it will prove mildly diverting for that series’ devoted fan-base. With a cover cleverly designed to resemble a tell-all supermarket tabloid, “Totally Charmed,” edited by Jennifer Crusie (Benbella Books, 2005) is a pop anthology by 21 contributors, who write science fiction, fantasy, or romance novels for a living. Here, they direct their attention to the television series Charmed and its three sibling witches, and it makes for entertaining reading. Can an ugly, and not especially bright, big lug, who makes his way through the mean streets with his oversized fists, still manage to garner a reader’s sympathies? Yes, if the eponymous anti-hero of “The Goon: Chinatown and the Mystery of Mr. Wicker” (Dark Horse Books, 2007) is any measure. Eric Powell’s graphic novel combines elements of gangland violence, urban vendetta, and fantasy – all wrapped up in a noir-looking setting, with a title character who does some bad things without being a wholly bad man.

More serious fare can be found in “We Are On Our Own” by Miriam Katin (Drawn & Quarterly, 2006). A memoir in the form of a graphic novel, it’s the harrowing true story of a young Jewish woman and her child who flee an upper middle class life in Budapest in a desperate bid to evade the Nazis. They enter a world of desperation, dread, and death – a world full of both the brutishness and the kindness of strangers. It’s a tale of survival and of faith tested to the breaking point; and it enchants with its opening panels, in which the black-inked characters of the Torah give way to the black-hearted swastika on a flag flapping outside a window.

After a much shorter than expected run in Toronto, where it had its world-premiere, the big musical stage adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s best known epic fared no better in its transplanted home of London. “The Lord of the Rings: The Official Stage Companion” by Gary Russell (HarperCollins, 2007) is a worthwhile illustrated look (in the nature of a souvenir book) at the script, music, design, and choreography of a show that was intended “to tell [a] huge, epic, and at the same time touching, intimate [story].” The musical may have fallen somewhat short of its mark, especially on the emotionally affecting side of that equation; but, it wasn’t for want of trying. Speaking of musical theater, “Little Musicals for Little Theaters” by Denny Martin Flinn (Limelight, 2006) is a must for everyone thinking of staging a show and for theater-goers alike! Billing itself as a reference guide to musicals “that don’t need chandeliers or helicopters to succeed,” it canvasses over 105 musicals – everything from the clothing optional Oh! Calcutta! to Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera and Godspell. Each entertaining entry has a synopsis of the play, a list of its musical numbers and analysis of its pros and cons (e.g. does it require musically accomplished singers?). The author is a writer, director, dancer, and choreographer, and it shows: He knows whereof he speaks. That goes for Scott Kaiser, the head of voice and text at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, too. His book “Shakespeare’s Wordcraft” (Limelight, 2007) is, as its title suggests, a study of the Bard’s use of language: “It’s about patterns – audible, discernible, memorable patterns that enter the ear and mix in the brain, giving meaning to the sounds and pleasure to the listener.” Thus, there’s form-shifting, as in “I followed fast, but faster did he fly;” repeating words in reverse order, as in “Your gentleness shall force, more than your force move us to gentleness;” and the repetition at the end of a phrase of the word with which it began, as in “Pride hath no other glass to show itself but pride.” The result is as accessible as it is fascinating. Elsewhere, there’s David Leopold’s “Irving Berlin’s Show Business” (Abrams, 2005), a lavishly illustrated guide to the great American composer and his music – and their lasting impact on popular culture: “Berlin’s Sisyphean task was to satisfy the public’s insatiable desire for new songs… Giving the people what they wanted was his uncanny talent.” The book is an engrossing look at the man, his career (on Broadway and in Hollywood), and his times. Opera buffs will appreciate “Start-Up at the New Met: The Metropolitan Opera Broadcasts 1966-1976″ by Paul Jackson (Amadeus Press, 2006), a chronicle of the Met’s first 140 performances at its home in the Lincoln Centre – despite the unfortunate scarcity of illustrations. If just listening to music isn’t enough, you’ll find practical guidance in “The Singer’s Companion: A Guide to Improving Your Voice and Performance” by Brett Monahan (Limelight, 2006). The book (and accompanying CD) will coach you on such subjects as breathing, phonation, resonance, and musicianship. Music also figures prominently in the “Rockabilly Legends” (Hal Leonard, 2007). The amply illustrated book, by Jerry Naylor & Steve Halliday, celebrates such 1950’s precursors to rock and roll as Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly, and it’s accompanied by a DVD with a 60-minute documentary that will be aired on PBS.

Wildly disparate aspects of popular culture figure in three recent books. “Pink Box: Inside Japan’s Sex Clubs” (Abrams, 2006) offers photographs by Joan Sinclair of Japan’s $20 billion a year commercial sexual services sector. Adorned in neon, or neon-bright posters, these ubiquitous places in Tokyo cater to fantasies – fantasies that run the gamut from the relatively demure to the dounright tawdry. The services they sell vary widely; but Sinclair’s unblinking look at “the silly yet serious world of erotic commerce” – a world where the Japanese people’s outward attributes of formality and restraint give way to shamless self-indulgence – are strangely fascinating, in the way that only the exotic practices of another culture can fascinate. The enduring fascination of a segment of our own culture for vampires – in film, literature, and, oddly-enough, in real life make-believe – is the subject of Eric Nuzum’s surprisingly entertaining “The Dead Travel Fast” (St. Martin’s Press, 2007). Part road-trip (from the Romanian haunts of historical mass murderer Vlad Dracula to U.S. Goth clubs inhabited by a very peculiar vampire wannabe clientele), part immersion in all things undead (from Dracula to Nosferatu and on to Buffy the Vampire Slayer), Nuzum essays a kind of cultural travelogue, and the result is hugely entertaining, whether you come to the subject with a pre-existing stake in it (no pun intended) or not. He’s a bit tough on Dark Shadows fans: “The convention was largely a collection of oddballs of every stripe. Of course, there were ‘normal’ folks there, but they weren’t taking the day percentage-wise.” And, he misses the real reasons that show captivated millions, assuming, unscientifically, that if some devotees of that or other fictional work (like Buffy) are inarticulate about the reasons for its allure, all must be. But the book’s tone is more often one of bemused affection, and it is often tremendously funny. Speaking of which, there’s another book that combines tell-it-like-it-is candor with riotously funny field studies in human foibles. That books is “Talk to the Hand: The Utter Bloody Rudeness of the World Today, or Six Good Reasons to Stay Home and Bolt the Door” by British columnist Lynne Truss (Gotham Books/Penguin, 2006). This little book with the long title is deliciously indigant, nailing its targets dead-on with unwavering accuracy and wit: “There are the things that drive me nuts when I’m out. I can’t stand people talking in the cinema. I can’t stand other people’s cigarette smoke… I am scared and angry when I hear the approach of young men drunkenly shouting. I can’t stand children skateboarding on pavements, or cyclists jumping lights and performing speed slaloms between pedestrians, and I am offended by T-shirts with ugly Eff-Off messages on them… What else? Well, I am incensed by graffiti, and would like to see offenders sprayed all over with car paint…” She’s also a litter-bug vigilante, but, for reasons of self-preservation, only if the offenders are under five foot two and younger than four. And, don’t even get her started on the bane of the civilized world known as cell-phones. Rush out and buy this book; it is irresistible!

There are also some first-rate new books in the areas of international relations, public policy, political affairs, and human rights. You might as well start with those that will elicit laughter rather than tears of indignation and chagrin. “Portfoolio 22: The Year’s Best Canadian Editorial Cartoons,” edited by Guy Badeux (McArthur & Co., 2006) deflates the pompous windbags we call leaders and skewers the sheer absurdity of much of what passes for policy debate in this world of ours. Remember the Ottawa mandarin David Dingwall – and his insistence on being “entitled to his entitlements?” Well, here we have a taxpayer brandishing a meat-cleaver who’s ready to talk “severance” with the self-entitlement-minded public servant. Elsewhere, relief to a swamped New Orleans gets bogged down in post-Katrina recriminations between federal, state, and city governments; while, further afield, a hot-head decries as blasphemous some seemingly innocuous editorial cartoons that dare to poke fun at Islamic extremism, but makes a hasty exit when the subject turns to the mistreatment of women, hostage beheadings, suicide bombings, and so-called “honor killings” perpetrated by those who loudly justify such actions in the name of Islam. “What Next?: And Other Recent Cartoons by Aislin” (McArthur & Co., 2006) is devoted exclusively to the Montreal Gazette’s editorial cartoonist Terry Mosher. Imagine the movie poster for Dumb and Dumber rejigged with the faces of George W. Bush and Stephen Harper, or a blue state/red state map of the U.S. re-labelled “Starbuck’s Nation vs. Wal-Mart Nation,” and you’ll get a sense of the pin-point accuracy of Aislin’s satire.

China’s increased prominence on the world stage these days could have a productive side-effect if its higher profile induces us to learn more about that country and its people. Less welcome, however, are early signs of a growing inclination in some quarters of the West to fashion China into the next “bogeyman du jour.” (After all, what would we do with ourselves if we didn’t have an implacable enemy with whom to grapple?) But, resisting a headlong rush to demonize another nation or culture does not oblige us to blindly ignore the challenges, or even dangers, it may pose. “Dragon Rising: An Insider Look at China Today” by Jasper Becker (2006) is one of the best books from National Geographic in recent years, and it’s one in which pride of place goes to words rather than pictures. Written by an experienced foreign correspondent, it’s a smart, elegantly written, and endlessly engrossing exploration of the Chinese people, culture, economy, and polity. It does not shrink from addressing the blood-stained savagery of China’s totalitarian regime, or the still massive disparities between hundreds of millions of rural peasants and the urbanites who’ve been lucky enough to become prosperous due to the economic boom. But, it makes its points by introducing us to individual Chinese from varied walks of life, like 20-year old Zhang Huali, who hopes that factory work and efforts to learn English may be her passport to a better life than the rural poverty from which she came. She’s “one of the 36 million peasant girls on whose slight shoulders China’s export miracle depends… [part of the] docile army willing to toil through the night…” Becker’s book is impossible to put down, and it is highly recommended! Nearly as riveting, “The China Fantasy: Why Capitalism Will Not Bring Democracy to China” by James Mann (Penguin Books, 2007) is a slimmer volume with a narrower objective. It proffers the persuasive (and disturbing) thesis that we have been hoodwinked about the claim that trade would help open China’s authoritarian political system: “People can wear tank tops or Armani suits and still not live under a democratic system.” A senior diplomatic correspondent, Mann argues that if anything, China’s utterly undemocratic one-party system is even more repressive now that it was in the aftermath of its bloody crackdown on unarmed Tiananmen Square protestors in 1989. Yet, Western societies are told over and over again by their own power elites that “engaging” with China will open the door there to basic freedoms and human rights. If we do business with oppressive tyrants, the contention goes, they’ll liberalize, whether they want to or not. Nonsense, retorts Mann; and worse than nonsense. He decries such claims as an outright lie, one that has been cynically promoted by those who are eager, for their own selfish reasons, to do business with China. Thus far, alas, there is no sign at all that organized political opposition or freedom of the press will be tolerated by the one-party tyranny with which some of us are so eager to do business. Even more troubling is Eamonn Fingleton’s thesis – in “In the Jaws of the Dragon: America’s Fate in the Coming Era of Chinese Hegemony” (St. Martin’s Press, 2008) – that we are not molding China, but that China is molding us – by penetrating American society “in ways that will slowly but surely undermine [our] values and institutions.” Much of the emphasis here is on economic matters, and the picture that emerges is a disturbing one. For instance: “No other major nation in modern times has been remotely so dependent on foreign creditors” as the United States is today; like other East Asian nations, China absorbs advanced technologies from abroad while jealously guarding any that happen to originate within its own borders (Japan’s pursuit of the same policy led to its monopolization of the electronics industry); and like Japan, South Korea, and other East Asian economic success stories, China has adeptly resisted meaningful free trade (how many North American cars are sold in those markets, for instance?), and a massive trade imbalance (in China’s favor) has been the result. It has financed its own growth with policies that force its citizens to save a significant part of their income, artificially producing an inexhaustable wellspring of capital. Meanwhile, China is accumulating levers of power, like the largest foreign currency reserves in world history and effective control of the Panama Canal. All of that might amount only to economic rivalry but for the fact that China’s ruthless one-party regime is implacably hostile to our core values and democratic way of life: “To say the least, China’s political agenda is utterly incompatible with that of the United States” and the rest of the West. Fingleton’s proposed corrective course entails, among other things, a withdrawal by the U.S. from the World Trade Organization, the concomitant adoption of protective tariffs, and measures to eliminate its massive budget deficit.