“The Writing of the Gods”

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

Key to a modern understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization is the Rosetta Stone. It has resided in the British Museum for 200 years now, its  magnetic attraction a timeless, and lucrative, draw for visitors. How did this nearly two-ton chunk of granodiorite get where it did, and how were those engraved images ever deciphered? In his well-researched and accessible book, The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone (Scribner, 2021), Edward Dolnick, an award-winning author and journalist, takes readers on a lively journey, answering these questions and introducing us to some intriguing characters along the way.

magnetic attraction a timeless, and lucrative, draw for visitors. How did this nearly two-ton chunk of granodiorite get where it did, and how were those engraved images ever deciphered? In his well-researched and accessible book, The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone (Scribner, 2021), Edward Dolnick, an award-winning author and journalist, takes readers on a lively journey, answering these questions and introducing us to some intriguing characters along the way.

Discovered in 1799 in the Nile delta town of Rashid (called Rosetta by the French) by Pierre-François Bouchard, an officer in Napoleon’s army, the Rosetta Stone appeared to offer a code-breaker’s key to deciphering the mysterious ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, as its three sections seemed to give the same information in different forms, the bottom portion written in easily translatable Greek. But the middle script and the hieroglyphs at the top eluded all efforts at translation, as Egyptian hieroglyphs had for centuries. Ancient Egyptian had ceased to be a spoken language since the seventh century, its place taken by Arabic, and the meaning of the symbols had been lost. In medieval times, Europeans came to believe that the hieroglyphs contained occult knowledge, their secret meaning known only to an initiated few; if only they could be deciphered, perhaps the secrets of the universe might be revealed. And so, when the British defeated Napoleon’s forces in Egypt in 1801, their seizure of the stone as a spoil of war and its transportation to the British Museum caused great excitement among scholars.

Though no prize money was on offer, the race to translate the writing on the Rosetta Stone was on. The chief contenders were the Englishman Thomas Young and the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion; they were as different in personality and scholarly approach as any two individuals could be, and Dolnick tells their story well. With his background in journalism, Dolnick is practiced at explaining complicated ideas in accessible terms, and his use of analogies makes complex ideas instantly understandable. “The Writing of the Gods” is an engaging scholarly detective story; readers will come away feeling both informed and entertained.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana. She is the author of “Thro’ the Rangeleys: A Photographic Journey of William H. Dodge” (Sunflower Books, 2020).

Copyright © 2022 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

Editor’s Note: The British Museum’s website has this to say about the Rosetta Stone:

“The writing on the Stone is an official message, called a decree, about the king (Ptolemy V, r. 204–181 BC). The decree was copied on to large stone slabs called stelae, which were put in every temple in Egypt. It says that the priests of a temple in Memphis (in Egypt) supported the king. The Rosetta Stone is one of these copies, so not particularly important in its own right. The important thing for us is that the decree is inscribed three times: in hieroglyphs (suitable for a priestly decree), Demotic (the cursive Egyptian script used for daily purposes, meaning ‘language of the people’), and Ancient Greek (the language of the administration – the rulers of Egypt at this point were Graeco-Macedonian after Alexander the Great’s conquest). The Rosetta Stone was found broken and incomplete. It features 14 lines of hieroglyphic script.”

For more, visit: https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-know-about-rosetta-stone

***************************************************

“State of Terror”

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

A novel co-written by two famous people looks at first glance like a gimmick, but fans of Louise Penny and/or Hillary Rodham Clinton will be unable to resist  at least taking a peek at “State of Terror” (Simon & Schuster/St. Martin’s Press, 2021). That peek can easily become a late-night book binge because this one is a page-turner! Plot-driven, the fast-paced tale races the clock as American Secretary of State Ellen Adams, backed by loyal friends and family, faces down bullies and gathers allies in a frenzied effort to thwart terrorists (at home and abroad) intent on detonating nuclear bombs hidden around the globe and in the U.S. It’s a bit of a roman à clef: Clinton has some scores to settle; and though some characters may seem obscure to non-Washington insiders, her portrayal of fictional former President Eric Dunn (a.k.a. “Eric the Dumb”), for example, is a skillful skewering of, well, you know who — it is amusing and scary as well. The hand of prize-winning Canadian author Louise Penny is clearly at work in the subtle characterizations of even minor characters, the expert placement of red herrings, and her signature one-sentence paragraphs which serve to heighten the tension and speed up the pace. Penny fans will also find a delightful surprise near the end of the story.

at least taking a peek at “State of Terror” (Simon & Schuster/St. Martin’s Press, 2021). That peek can easily become a late-night book binge because this one is a page-turner! Plot-driven, the fast-paced tale races the clock as American Secretary of State Ellen Adams, backed by loyal friends and family, faces down bullies and gathers allies in a frenzied effort to thwart terrorists (at home and abroad) intent on detonating nuclear bombs hidden around the globe and in the U.S. It’s a bit of a roman à clef: Clinton has some scores to settle; and though some characters may seem obscure to non-Washington insiders, her portrayal of fictional former President Eric Dunn (a.k.a. “Eric the Dumb”), for example, is a skillful skewering of, well, you know who — it is amusing and scary as well. The hand of prize-winning Canadian author Louise Penny is clearly at work in the subtle characterizations of even minor characters, the expert placement of red herrings, and her signature one-sentence paragraphs which serve to heighten the tension and speed up the pace. Penny fans will also find a delightful surprise near the end of the story.

And though the pairing of Penny and Clinton may look gimmicky, in fact, the two have been friends for years, connecting in person at a time of personal difficulty for both. Following the suggestion of a publisher friend, they decided to write a book together, collaborating long-distance, selecting their subject from an alarming list of nightmarish possibilities that kept Clinton awake at night during her time as Secretary of State. The resulting thriller, while including loyal friends and selfless heroes, also features enough sinister villains, misguided zealots, treacherous operators, and frightening up-to-the-minute political scenarios to keep readers awake at 3:00 a.m. It’s not great literature, but anyone needing a little distraction from the routine anxieties of daily life these days will not be disappointed.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana. She is the author of “Thro’ the Rangeleys: A Photographic Journey of William H. Dodge” (Sunflower Books, 2020).

Copyright © 2022 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

***************************************************

“The Glass Hotel”

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

“Station Eleven,” by Canadian-born author Emily St. John Mandel, was a major popular and critical success; it was also a hit  with my book club! For Mandel, considering what to write next had to have been intimidating, and so, prudently, in “The Glass Hotel” (published in the U.S. by Knopf and in Canada by HarperCollins, both 2020), she has written a very different kind of novel, centering on a catastrophe of a quieter kind, but, for those affected, utterly devastating. Building on the story of a financial collapse, Mandel asks some big questions about right and wrong, how we know what we want to know, and what we choose not to.

with my book club! For Mandel, considering what to write next had to have been intimidating, and so, prudently, in “The Glass Hotel” (published in the U.S. by Knopf and in Canada by HarperCollins, both 2020), she has written a very different kind of novel, centering on a catastrophe of a quieter kind, but, for those affected, utterly devastating. Building on the story of a financial collapse, Mandel asks some big questions about right and wrong, how we know what we want to know, and what we choose not to.

Named for the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, Vincent is working as a bartender in a five-star hotel in northern Vancouver Island, the vast windows looking out into the wilderness, when a cryptic message is scratched into one of those big windows: “Why don’t you swallow broken glass.” The mystery of who wrote it and why centers a narrative that moves backward and forward in time, as we encounter other metaphors – water, mirrors, camera lenses – that also work as reflective barriers, some permeable, others not. The hotel is where Vincent and others meet their destiny in the person of Jonathan Alkaitis, a wealthy financier whose investment program promises unbelievable returns: a Ponzi scheme, as it turns out. When it collapses, the victims must confront their own greed and willingness to be deceived. As one young analyst in Alkaitis’s firm puts it, “It is possible to know and not know something.”

There are many ghosts. Are they real, or are they manifestations of guilty consciences? As with the ghost of Hamlet’s father, it is not always possible to tell. In prison, Alkaitis is visited by the spirits of his defrauded investors. Vincent sees her drowned mother, or thinks she does, in a crowd and in other circumstances. The dead, it seems, move between worlds, as if in parallel universes, where different choices, different realities, follow their own rules.

Structurally, “The Glass Hotel” is brilliant, its complexities serving to deepen the reader’s appreciation for the narrative and the moral questions being posed. But it is also a satisfying read simply for its story and characters. My book club has just one rule for our selections: they must generate interesting discussion. “The Glass Hotel” certainly delivered on that promise.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana. She is the author of “Thro’ the Rangeleys: A Photographic Journey of William H. Dodge” (Sunflower Books, 2020), which is reviewed in this magazine.

Copyright © 2020 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

***************************************************

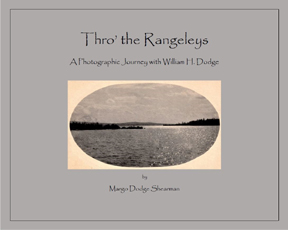

Thro’ the Rangeleys: Photographic Evocations of the Past

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

“In August 1893, my great-grandfather, William Dodge of Lowell, Massachusetts, and a few friends traveled north for a fishing trip, and William brought along something special: a camera.” In

“Five of a kind?” (photo by William H. Dodge) © 2020 by Margo Dodge Shearman

“Thro’ the Rangeleys: A Photographic Journey of William H. Dodge” (Sunflower Books, 2020), Margo Dodge Shearman has assembled 33 pages of black-and-white and sepia-toned images from that long-ago trip to the Rangeley Lakes of western Maine, and they are a captivating glimpse into life 127 years ago. We see the natural features of this untamed 19th century corner of America, a semi-wilderness of a logging area that began to draw hunters, fishers, and small boaters after the Civil War: We can practically feel the spray coming off a waterfall, and there’s tranquility in an image of three men in a rowboat passing beneath a stand of spruce and birch trees. But, there’s so much more here than mere water and woods. The most memorable images are those that have a human connection, like a pair of crumpled, well-worn shoes that look oddly poignant; a sextet of fish waiting for the frying pan; and a side-view of a man leaning back on a chair, pipe in hand, while his outstretched legs rest on the sill of the window through which he is

© 2020 by Margo Dodge Shearman

gazing. A young woman with pre-Raphaelite locks and long dress has her eyes downcast on the guitar she’s playing in a doorway. A man outside a log cabin crouches in front of a simple cooker as it gives forth a cloud of white smoke. An impressive wooden lodge with the curious name of ‘Mooselookmeguntic House’ perches on a shore. And, best of all, there’s a portrait of three card players that looks for the world like it’s a still image from a silent movie: indeed, two of these gamesters resemble Laurel and Hardy, and one of them is mischievously showing off a most unlikely winning hand – to wit, ‘five of a kind.’

The result is a highly evocative, nostalgic window into a few days in the lives of a past generation. We were struck by the gentle, touching quality and charm evoked by these images. And the author’s seven-page introduction completes the spell, with her engaging account of her forebear’s life. (Indeed, her delicate yet vivid opening paragraph leaves us hoping that she’ll try her hand at short fiction and/or literary travel writing.) A professional color mixer and designer for a big carpet mill, William H. Dodge was a husband and father, a bicycle racer, a watercolor painter, and an amateur photographer of some note; he also had success in local politics – until his life went in an unexpected and bittersweet direction. Shearman’s verbal portrait of the photographer is almost as evocative as his images. Together, they make for some enticing time travel.

John Arkelian is an award-winning journalist and author.

Copyright © 2020 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: “Thro’ the Rangeleys” is available in the U.S. at Amazon; Barnes & Noble; and BookBaby.com. In Canada, look for it at Amazon.ca and Chapters/Indigo Books. Visit the author at www.throtherangeleys.wordpress.com and www.facebook.com/MargoDodgeShearman

***************************************************

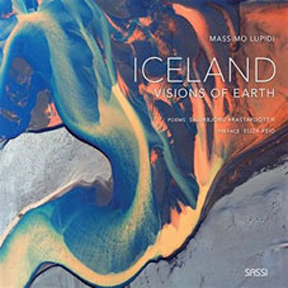

Iceland: Visions of Earth

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

Iceland is an elemental place, a primordial world on the morning of

Langisjor Lake — From “Iceland: Visions of Earth” (Sassi, 2017) – photograph © 2019 by Massimo Lupidi.

Creation, a place where the very bones of the earth are manifest. Raw, starkly beautiful, otherworldly, yet also unmistakably terrestrial, it’s a dizzying, breathtaking escape into an earth untouched by man. In the introduction to his hardcover book, Iceland: Visions of Earth (Sassi, 2017), Italy’s Massimo Lupidi says, “Suddenly what was far away becomes close, what was impossible becomes possible, what was a dream becomes reality.” And his glorious photographs make those words palpable, startling… revelatory.

Aquamarine icebergs float off the shore at Jökulsárlon; a rough-hewn basalt cavern straight out of Fäerie opens onto the rugged black beach of Reynisfjara; the ‘peaks of heaven’ are worthy

Ófærufoss waterfall — From “Iceland: Visions of Earth” (Sassi, 2017) – photograph © 2019 by Massimo Lupidi.

of their name on the icy, mist-shrouded heights of Snaefellsjökull glacier; bubbling hot springs, sulfurous acidic mud, and steam vents conjure a Martian or Venusian landscape; there are lakes (Saudafellsvatn, Saudleysuvatn, & Altavatn) so blue they’ll make you weep. Obsidian hexagonal columns of basalt line the Hanging Falls (Litlanesfoss), while other waterfalls (Gullfoss, Seljalandsfoss, Dettifoss, Ofaerufoss, & Fjallfoos) are the wild, elemental, northerly kin of Niagara – with a palette as diverse as turquoise and boiling white.

Giants slumber on the shores of Kleifarvatn Lake, their sinuous recumbent forms blanketed by sensuously smooth stone. Water and rock meet in frenzied, swirling anarchy beneath the cliffs of the

“Iceland: Visions of Earth” (Sassi, 2017) – photograph © 2019 by Massimo Lupidi.

Westfjords. An ice cave is Merlinesque – a place of adamantine clarity and of conjuring beyond the ken of mere mortals. The lunar mountainscape at the Öxaráfoss gorge, a place where tectonic plates have riven the earth, gathers in silent expectation around its waterfall. Lichen and moss soften the rocks at the Eagle Fjord, with its stunning vista; a 767-meter high butte (Lömannúpur) towers above a desert like a massive obelisk put there by God; and the soft-crowned undulating mountains around Long Lake (Langisjór) gladden the heart with their beauty.

Some impressionistic images (as on the book’s cover) with a swirl of soil and water are interesting; but the lion’s share of the book is devoted to landscapes – and they are glorious, achingly so. Lupidi’s images quicken the soul, just as Iceland does. His book has short bits of poetry by Sigurbjorg Thrastardóttir. One of them captures the wild spirit of this place, where the imagination becomes tangible: “…and the cliffs from his bones / and the rocks from / his teeth, the trees from / his hair and the sea from his blood…” (from “Homemade,” or “The Creation of the World from the Body of Ýmir”). This captivating book makes us yearn to return to Iceland, a place, as Lupidi says, which is “fabulously beyond our wildest imaginings: a natural wonder forged by fire and tempered by ice.”

John Arkelian is an award-winning journalist and author who waxes poetical in the presence of his beloved Iceland.

Copyright © 2019 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

“The Marches” – On the border of England & Scotland

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

I was expecting Rory Stewart’s “The Marches: A Borderland Journey between England and Scotland” (Houghton Mifflin  Harcourt, 2016) to be a trudge along Hadrian’s Wall, with scholarly forays into the history of Roman military occupation, the Romantic poetry of the Lake District, and the mythic realm of Walter Scott’s Scotland. Instead, it turned out to be a complicated journey through multiple levels of time and space, with a guide whose background and travels were similarly layered and contradictory.

Harcourt, 2016) to be a trudge along Hadrian’s Wall, with scholarly forays into the history of Roman military occupation, the Romantic poetry of the Lake District, and the mythic realm of Walter Scott’s Scotland. Instead, it turned out to be a complicated journey through multiple levels of time and space, with a guide whose background and travels were similarly layered and contradictory.

Politician, diplomat, and author of the best-selling The Places in Between, which recounts his travels in Afghanistan, Rory Stewart has had a varied career, ranging from military service to Member of Parliament for ‘Penrith and the Border,’ and he uses the insights gained from this complex background to try to understand the Middlelands, the territory ranging from northern England to the edge of the Scottish Highlands. His traveling companion, at least at the start of the journey, is his aging yet vital father, a retired Foreign Service Officer whose contradictions and opacity are equaled only by his energy and charm; and the son’s effort to understand his father is another level of the trip.

Within the framing device of the walking tour, we learn quite a bit about the different cultures of the region: the pre-Roman tribal cultures; the Roman military culture of the frontier; the people of Cumbria and Northumbria; the Norse; the Normans; the more recent Scots and English. No single people dominate the region for long, Stewart finds, and a sense of identity among inhabitants of the land remains elusive. Stewart is an engaging conversationalist, and he chats up various people he meets along the way, trying to get a sense of how they see themselves as inhabitants of these borderlands. Often he comes away baffled by their lack of historical awareness; where he was expecting to find some sort of cultural cohesiveness, he instead encounters change and contradiction, as perhaps anywhere in modern Britain.

The final portion of the book focuses squarely on Stewart’s relationship with his by now physically frail father, whose final decline is described with sensitivity and care. The elder Stewart’s attitude toward life has always been to Get On With It, an approach the son admires but does not entirely share. Their relationship is, nevertheless, a close one, and the old man’s death feels mythic, the symbolic passing not just of a generation but of the empire too. The book sometimes feels like a bit of a jumble, with its starts and stops, its unmet expectations, its abrupt shifts in time and tone, but it is an engaging journey all the same, a thoughtful reflection on our complicated times in the company of a keenly observant and insightful writer.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana.

Copyright © 2018 by Margo Shearman-Howard

***************************************************

Unholy Alliance: Trump and the Evangelicals

© By John Arkelian

Of all the confounding things about Donald Trump’s rise to political power in the United States, one of the most unexpected is the fact  that a large majority of evangelical Christians supported him. How could a man with no discernible religious conviction, a man whose words and actions seem to daily contradict Christian virtues of compassion, humility, integrity, and godliness attract the support of the very people who strive to exemplify those qualities? The answer to that question is the subject of “Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump” (Eerdmans, 2018) by John Fea, who is both an historian and a practicing evangelical. Evangelicalism is the movement in Christianity which emphasizes salvation through faith in Christ’s atonement for our sins; the importance of conversion, or a ‘born-again’ experience; Biblical authority in understanding our relationship with God; and the duty of the faithful to spread the word. Evangelicals (like others of religious conviction) attach great value to a person’s character; yet, a staggering 81% of white evangelicals voted for “a moral monster… a profane man – a playboy and adulterer who worshipped, not at the throne of God, but at the throne of Mammon.” Fea makes a convincing argument that evangelicals were motivated by three things – fear, power, and nostalgia.

that a large majority of evangelical Christians supported him. How could a man with no discernible religious conviction, a man whose words and actions seem to daily contradict Christian virtues of compassion, humility, integrity, and godliness attract the support of the very people who strive to exemplify those qualities? The answer to that question is the subject of “Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump” (Eerdmans, 2018) by John Fea, who is both an historian and a practicing evangelical. Evangelicalism is the movement in Christianity which emphasizes salvation through faith in Christ’s atonement for our sins; the importance of conversion, or a ‘born-again’ experience; Biblical authority in understanding our relationship with God; and the duty of the faithful to spread the word. Evangelicals (like others of religious conviction) attach great value to a person’s character; yet, a staggering 81% of white evangelicals voted for “a moral monster… a profane man – a playboy and adulterer who worshipped, not at the throne of God, but at the throne of Mammon.” Fea makes a convincing argument that evangelicals were motivated by three things – fear, power, and nostalgia.

Fear was a visceral part of the evangelical psyche from the nation’s colonial beginnings. Lately, that sense of unease and encroaching danger is characterized as a ‘culture war’ that pits social conservatives against abortion, same-sex marriage, and real or perceived infringements on religious liberty. The trend-line (and changing demographics) seems to be against them, even as the tide of progressive niche-causes writ large threatens to overwhelm them. So, they yearn for a strong-man to deliver them (and to deliver some Supreme Court seats while he’s at it), forgetting God’s admonition to ‘fear not’ and opting instead to obtain and wield political power in a vain attempt to freeze a particular model of culture into place.

But a preoccupation with getting and keeping political power is, ultimately, inimical to the very values that evangelicals desperately seek to protect. It prompts them to overlook glaring character flaws, to elect a petulant, grandstanding egotist who embodies all that is intemperate, small-minded, crass, and vindictive, in exchange for the promise of a social conservative on the bench of the nation’s highest court and the expected retrenchment of secularization. Power is by its nature seductive, turning those it entangles into “court evangelicals” who seek influence by flattering (and making excuses for) the worldly king, even as they neglect their duty to be a “faithful presence.”

Not only do too many evangelicals seek to reclaim a world they see in danger of disappearing, they also mistake their own nostalgia for a fact-based reading of history: Asserting that America was founded as a Christian nation over-simplifies a more complex reality. And their new champion’s favorite call to arms, “Make America Great Again,” is nothing but a meaningless slogan. When exactly was the nation “great?” What made it great – and for whom? Was it ever great, from the perspective of blacks or native-Americans?

This fascinating, informative, and persuasive book offers welcome insights and timely reminders: It is a mistake to conflate our own religious faith and moral precepts with the wider culture in which we live, or to try through political power to remake the latter in our own preferred image. Nothing should cause us to forget the importance of character: only a man (or woman) of integrity is fit to lead a nation, for “republics rise and fall based on the virtue of the people and their leaders.” And, as Christians, we are called upon to embrace hope instead of fear, humility in lieu of power, and history in place of fanciful nostalgia.

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

Leading an Improvisational Life

© By John Arkelian

All self-help and exhortation-driven books seem inevitably prone to treading precariously close to the precipice of the clichéd and the  obvious. Often, there’s something faddish about their latest prescription for weight-loss, happiness, conjugal harmony, renewed spiritual faith, material success, coping with grief, or whatever else may ail you. They implicitly promise (or, at the very least, hint at) the profound and the original, when all they can possibly deliver is the mundane, the gimmicky, or, at best, the commonsensical. In God, Improv, and the Art of Living (Erdmans, 2018), MaryAnn McKibben Dana attempts to extend the practices and principles of a niche pursuit – namely, theatrical improvisation – to more general applicability as life-lessons. Paradoxically, so much of the underlying niche pursuit adheres to the book’s prescriptions that non-initiates (those of us who do not do ‘improv’ for fun or a living) may feel a tad detached and distant from its salutary lessons for life. Still, Dana’s approach is accessible, practical, upbeat, and witty. An itinerant Presbyterian preacher and lecturer, Dana uses improv as a metaphor for life – and how we live it.

obvious. Often, there’s something faddish about their latest prescription for weight-loss, happiness, conjugal harmony, renewed spiritual faith, material success, coping with grief, or whatever else may ail you. They implicitly promise (or, at the very least, hint at) the profound and the original, when all they can possibly deliver is the mundane, the gimmicky, or, at best, the commonsensical. In God, Improv, and the Art of Living (Erdmans, 2018), MaryAnn McKibben Dana attempts to extend the practices and principles of a niche pursuit – namely, theatrical improvisation – to more general applicability as life-lessons. Paradoxically, so much of the underlying niche pursuit adheres to the book’s prescriptions that non-initiates (those of us who do not do ‘improv’ for fun or a living) may feel a tad detached and distant from its salutary lessons for life. Still, Dana’s approach is accessible, practical, upbeat, and witty. An itinerant Presbyterian preacher and lecturer, Dana uses improv as a metaphor for life – and how we live it.

At the heart of the improvisational technique is “responsiveness, a willingness to embrace a call when it comes, to receive a gift when it is offered.” For the person of faith, that means “a lifelong journey of responding to God’s call.” In our daily lives, that means learning to say “yes” to whatever situation presents itself. Those who do improv on a stage are expected to take the proverbial ball and run with it, by accepting a premise or situation and then building on it – what the author calls “yes, and…” There’s no room for passivity on the improv stage, or in life: “We are what we do – not what we say we’ll do, not what we hope to do someday.” We need, instead, to be fully active participants in the unfolding of our own stories: Even on stage, “improvisation does not mean being funny. It means being human [and] being human in improv means going for what’s truthful.”

There are lessons here for active listening, for spontaneity, for creative collaboration, for generously accepting what we are offered by others, for seizing the opportunities presented by life, for ignoring the inner voice that whispers that we’re inadequate or apt to look foolish, for not letting an idea of perfection get in the way of the graspable good in the here and now, and for embracing the unexpected: “The unforeseen happens. Plans fall through. People get sick. Marriages end. The plant closes down. Loved ones die. Our job as improvisers is… to put together a life in the wake of these things – maybe not the life we had planned, but a good life… fashioned out of what’s at hand.” And Dana rejects the idea of a God who pulls strings or has a single plan for us mapped out in advance. Instead, interestingly, she argues that God, too, is an improviser, innovatively interacting with each of us in the face of ever-changing circumstances. The future is in a perpetual state of flux, never predictable, never set in stone. Its eddies and currents (and occasional tidal waves) take us here and there – but an improvisational life needs no fixed destinations. It rejoices in creating something good from the unpredictable, just as God delights in creatively extemporizing right along with us in the ad-libbed dance of life.

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

Cry for Chiweshe

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

A life of dedicated service collides headlong with heavy-handed  injustice in “Cry for Chiweshe” (2017), Tina Ivany’s absorbing account of a Canadian medical missionary’s ouster as head of a hospital in rural Zimbabwe. As chief medical officer and surgeon at Howard Hospital, Dr. Paul Thistle oversaw the medical care and well-being of a quarter-million people in the Chiweshe region. Beloved by the locals (he married a local nurse, Pedrineh), Thistle’s 17 years of service came to an abrupt end in 2012 when the Salvation Army suddenly relieved him – seemingly without reasonable or just cause.

injustice in “Cry for Chiweshe” (2017), Tina Ivany’s absorbing account of a Canadian medical missionary’s ouster as head of a hospital in rural Zimbabwe. As chief medical officer and surgeon at Howard Hospital, Dr. Paul Thistle oversaw the medical care and well-being of a quarter-million people in the Chiweshe region. Beloved by the locals (he married a local nurse, Pedrineh), Thistle’s 17 years of service came to an abrupt end in 2012 when the Salvation Army suddenly relieved him – seemingly without reasonable or just cause.

The author contrasts the Thistles’ selfless service with the opaque, arbitrary, and possibly corrupt machinations of the church bureaucracy. Thistle was very effective in attracting financial support for the hospital from donors in Canada; but it is suggested that church officials in Zimbabwe (some of whom were closely connected to the corrupt, autocratic regime of Robert Mugabe and the ZANU-PF Party) improperly skimmed some of those monies – an allegation that could use more elaboration. Some of the (seemingly spurious) counter-allegations made by the church against Thistle aren’t fully specified till late in the book, which is a curious choice. Another imponderable for readers is why Howard Hospital declined so precipitously after the Thisles’ forced departure: Where were the able staff and durable infrastructure to keep it self-sustaining? Being so dependant upon one man seems not to have been good for it in the long run.

The author weaves an engrossing story, which encompasses both the ‘macro’ scale (bureaucratic dissembling) and the ‘micro’ (admirable individuals making the world a better place one day at a time). Tina Ivany knows her subject and adeptly holds our interest from the first page to the last. Little ‘extras’ that caught our eye are the enchanting cover art by Thistle’s predecessor and mentor (Dr. James Watt), and Ivany’s highly apt choice of quotations to open each chapter, including one by Paul Thistle himself: “Vision without action is but a daydream.”

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

Remembering Jonathan Frid

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

Lamentably underappreciated in his native Canada, Jonathan Frid’s transit from Shakespearian stage actor to star of a Gothic romance  of a television drama, “Dark Shadows” (1966-71), earned him a lasting place as an icon of American popular culture. Frid’s classical theater roots gave him real gravitas and made him a natural for the role of Barnabas Collins, the haunted, tragic antihero who happened to be a 175-year-old vampire. In “Remembering Jonathan Frid,” edited by Nancy Kersey & Helen Samaras (Evil Twin Publications, 2014), over two dozen fans, friends, and co-workers contribute their recollections of the actor and the man, after his death in April 2012. Few of the contributors are professional writers, but their contributions range from serviceable to very good. What’s best of all is sharing so many diverse impressions of the man whose work made such a lasting impression on audiences. There are insights here, for example, into Frid’s personal shyness and his credentials as a loner: Intense interest in a project might fade abruptly, and, with it, the working, and even personal, relationships associated with that passing passion. An instance of kindness to a young fan coexisted with discomfort and sometimes outright annoyance with awe-struck, hero-worshipping admirers.

of a television drama, “Dark Shadows” (1966-71), earned him a lasting place as an icon of American popular culture. Frid’s classical theater roots gave him real gravitas and made him a natural for the role of Barnabas Collins, the haunted, tragic antihero who happened to be a 175-year-old vampire. In “Remembering Jonathan Frid,” edited by Nancy Kersey & Helen Samaras (Evil Twin Publications, 2014), over two dozen fans, friends, and co-workers contribute their recollections of the actor and the man, after his death in April 2012. Few of the contributors are professional writers, but their contributions range from serviceable to very good. What’s best of all is sharing so many diverse impressions of the man whose work made such a lasting impression on audiences. There are insights here, for example, into Frid’s personal shyness and his credentials as a loner: Intense interest in a project might fade abruptly, and, with it, the working, and even personal, relationships associated with that passing passion. An instance of kindness to a young fan coexisted with discomfort and sometimes outright annoyance with awe-struck, hero-worshipping admirers.

There are poignant moments regarding Frid’s fading memory in his older years, and an amusing one about a swimsuit malfunction. However, an account of his confusion and frailty during the filming of Tim Burton’s awful, franchise-killing 2012 “Dark Shadows” movie parody, contributed by Frid’s Shadows’ co-star, feels intrusive on his privacy. At that point, mere months before his death, Frid was not at his best; he should never have been cajoled into traveling to the U.K. for his momentary cameo. And, it’s a good bet that he never would have gone, if he’d known the intention of Burton and clownish leading man Johnny Depp was to mock the character and story with which Frid was so closely associated.

There’s a bright and perceptive account of a fan’s journey from childhood to adulthood; overly gushing remarks elsewhere (describing Frid as “a giant of a man” – precisely the kind of abject adulation Frid disliked); an apt description of “Dark Shadows’” world as its own unique “Never-Never Land;” and a section that demonstrates that fan artist Sherlock is as good at writing as drawing. And there’s humor, too: “’Jonathan Frid knows who I am?’ I gushed silently, completely forgetting about the name tag I was wearing – made from red construction paper in the shape of a drop of blood, because that’s how we rolled back then.” There’s a healthy dose of nostalgia here – for the series, the star, and the unique persona that captivated rapt viewers for over 50 years.

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: For Artsforum’s own remembrance of Jonathan Frid, see: https://artsforum.ca/other-media/tv-radio

***************************************************

Station Eleven

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

The post-apocalyptic novel seems to have an enduring appeal, speaking to us as it does of the beauty and fragility of modern life.  The genre is usually grim, featuring struggling survivors, barbarians who have broken through the gates, and a sense of inevitability. “Station Eleven” (HarperCollins, 2014), includes these elements, but also a great deal more. Its author, British Columbia-born Emily St. John Mandel, has crafted a narrative design that weaves together Shakespearean archetypes and contemporary pop culture, all in a style that is both poetic and absorbing.

The genre is usually grim, featuring struggling survivors, barbarians who have broken through the gates, and a sense of inevitability. “Station Eleven” (HarperCollins, 2014), includes these elements, but also a great deal more. Its author, British Columbia-born Emily St. John Mandel, has crafted a narrative design that weaves together Shakespearean archetypes and contemporary pop culture, all in a style that is both poetic and absorbing.

The story opens with the on-stage death of Arthur Leander, as he plays the old king in Lear, in an innovative production in Toronto. This death is a harbinger; even as the play starts, a flu pandemic is beginning its worldwide sweep, killing 99 percent of humanity. The story moves back and forth in time, before and after the terrible event, tracing the lives of the survivors:

“Twenty years after the end of air travel, the caravans of the Traveling Symphony moved slowly under a white-hot sky…. There was the flu that exploded like a neutron bomb over the surface of the earth and the shock of the collapse that followed, the first unspeakable years when everyone was traveling, before everyone caught on that there was no place they could walk to where life continued as it had before and settled wherever they could…”

Even in death, Arthur Leander, like the old magician Prospero, brings together people from the diverse strands of his complicated life, a pattern the reader begins to glimpse as the tale progresses. At the center is a comic book, more like an artistic graphic novel, whose protagonist’s struggles mirror those of the survivors. There are moments of shock and horror; a sense of sorrow and great loss suffuses the lives of those old enough to remember the earlier time; but the younger generation, who never knew airplanes or cell phones, or even electricity, move bravely into the new world, rebuilding and reconnecting, as humanity starts the project of civilization all over again.

As you read this award-winning novel, prepare to experience gratitude for the comfortable lives we lead today and the good people we share our lives with, a sense heightened by an awareness of how easily it could all be snatched away. And keep an eye out for this gifted author; this book shows great promise for the future.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana.

Copyright © 2018 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

***************************************************

Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies

© Reviewed by Margo Shearman-Howard

Ben Macintyre is a truly gifted writer. Fascinated as he is by the  backstage maneuvering of World War II, he has a proven record as a popular historian, rediscovering the long-hidden stories of those behind-the-scenes heroes who played such an important part in winning the war against the Nazis. In “Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies” (Crown/Archetype, 2013), Macintyre tells the story of the motley crew of double agents and their handlers who were able, through a combination of determination, skill, and luck, to convince the Germans that the main Allied invasion of France in June 1944 would take place at Calais, thus diverting attention and military forces from the real target, the beaches of Normandy. Under the heading Operation Fortitude, Tommy Argyll “Tar” Robertson of MI5 headed a group of agents that included a wealthy bisexual Peruvian, a Spanish expert in chicken farming, a Polish patriot, a volatile, dog-loving Frenchwoman, and a Serbian playboy. In the looking-glass world of espionage, these agents performed a delicate balancing act in the grey zone between truth and deception, and the stakes could not have been higher.

backstage maneuvering of World War II, he has a proven record as a popular historian, rediscovering the long-hidden stories of those behind-the-scenes heroes who played such an important part in winning the war against the Nazis. In “Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies” (Crown/Archetype, 2013), Macintyre tells the story of the motley crew of double agents and their handlers who were able, through a combination of determination, skill, and luck, to convince the Germans that the main Allied invasion of France in June 1944 would take place at Calais, thus diverting attention and military forces from the real target, the beaches of Normandy. Under the heading Operation Fortitude, Tommy Argyll “Tar” Robertson of MI5 headed a group of agents that included a wealthy bisexual Peruvian, a Spanish expert in chicken farming, a Polish patriot, a volatile, dog-loving Frenchwoman, and a Serbian playboy. In the looking-glass world of espionage, these agents performed a delicate balancing act in the grey zone between truth and deception, and the stakes could not have been higher.

The author of Operation Mincemeat and Agent Zigzag has crafted another engaging historical narrative, based on solid research and with a keen eye for the odd but telling detail. For example, included in the generous photo selection are pictures of the dummy tanks and fighter planes poised to “attack” Calais and thus deceive German reconnaissance missions; the photo of four men lifting one of the inflatable tanks is amusing, yet the purpose behind it was deadly serious. Even when you know what the outcome of D-Day will be, Macintyre maintains the suspense of this real-life thriller so effectively that you may find yourself reading later into the night than you had planned, just to see what happens next.

Margo Shearman-Howard, who is one-quarter Canadian, writes and edits from South Bend, Indiana.

Copyright © 2018 by Margo Shearman-Howard.

***************************************************

A First Novel Interview with Julia Rath

© By John Arkelian

When the protagonist of the new novel “Split Self / Torn Mind” muses about laboratory animals being “helpless cogs in the wheel of scientific… experiments,” the fact that she may share their fate never crosses her mind. After all, what does a university psychology professor know about being kidnapped, escaping, and getting caught up in covert bio-weapons experimentation? Dr. Theresa Hightower is about to find out. Unlike a conventional ‘whodunit,’ we know almost from the get-go who is responsible for the unexpected troubles in the hitherto staid life of its academic heroine. The engine of this story, from first-time novelist Julia Rath, is suspense as opposed to mystery: We start by knowing some of what happened; what follows is an unfolding of the why.

Rath chose the University of Chicago as her novel’s setting because it is her own alma mater, and she’s familiar with the place and the rhythms of life there. And, the campus has been home to covert scientific projects before, as it hosted elements of the Manhattan Project in 1942, which, of course, led to the Allies’ development of the atomic bomb in World War Two. (A Henry Moore sculpture on campus is dedicated to atomic energy.)

From her own academic background in sociology, Rath started with non-fiction in 2013, in the form of “Conquering Your Own Sleep Apnea: The All-Natural Way,” a self-help book intended for the general reader. Was it challenging to change gears so radically, for the leap into suspense fiction? “It is more difficult to write fiction,” Rath says. “With non-fiction, you do the research, cull the facts,” and so forth. But fiction entails some very different ingredients, foremost among them, emotion: Capturing the subjective perspective of your characters – how they feel about the events that befall them – calls upon very different skills from the author. And there’s the very practical question about where to end chapters in a novel: In Rath’s chosen genre, the idea is to end on a suspenseful note to carry the reader on to the next chapter. And, while a novel is by definition the stuff of fiction; it is important to ground it in sufficient reality to give the reader something to recognize and grab hold of.

“Writing has always been a means of escape,” Rath says. She’d tried her hand at a screenplay or two before, but her novel is the first fiction project she’s taken to completion; and she is already at work on a second novel (it’s not a sequel), mere months after “Split Self / Torn Mind” appeared (in November 2017). If there’s a spectrum from ‘pulp’ to ‘literary’ fiction, where did Rath aim to situate her inaugural book on that spectrum? “That’s the magic question. I’m trying to do both at the same time.” Its pulp credentials come with its suspense genre, but she hopes that her book’s pointed observations about academia lend it more depth. “You can read it at a superficial or deeper level,” especially as it peeks behind the curtains of university life. It’s meant to be a page-turner; but Rath is also “looking at the underbelly of academic life” with a view to “puncturing the pomposity.”

I note that Rath is a master at self-reinvention. Some of her guises have been as an academic herself, as a sociologist, a radio show producer, the author of a medical self-help book, and now a novelist. What prompts her to try such eclectic roles on for size? “A friend called me ‘versatile,’” laughs Rath. “Most of us have different aspects to our personality.” (Her book’s title gives literal voice to that observation.) “I like to try different things. I enjoy the creative process.” She never ended up with the full-time tenure track post in academia that she anticipated, so eclecticism (she’s also a composer of music) is as much professional practicality as it a reflection of her personality. Rath’s post-secondary education took her from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to Manchester, England; to the University of Oxford; to George Washington University (in Washington, D.C.); and finally to the University of Chicago, where she completed her doctorate. Post-doctoral work took her to New York City for behavioral sciences training that straddled the disciplines of psychology, sociology, and medicine and involved work on substance abuse.

Rath’s novel is self-published; but “the old stigma” that method of getting one’s work into print once entailed “isn’t there now.” “Nowadays, self-publishing is much more in vogue. [Traditional] publishers don’t like to take risks: A celebrity can write junk and they’ll publish it” because it’s apt to sell on account of its author’s name alone. I observe that the same unfortunate phenomenon too often insinuates its way into political affairs, as dynasties of Kennedys, Trudeaus, and Bushes bear witness – not to mention the noxious, celebrity-fueled electoral success of one Donald Trump. But unlike the last name on that list, Rath has no interest in “pandering” to the lowest common denominator: “Standards are important.” Hallelujah to that, say I!

John Arkelian is editor of Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: “Split Self / Torn Mind” (2017) is available directly from its publisher (VirtualBookworm.com) or through Amazon (in either softcover or e-book form). The novel has adult content and is intended for ages 18+.

***************************************************

On the Compatibility of Science and Religion

© By John Arkelian

Are science and religion compatible? Or are they locked in an  implacable conflict? In his new book, a professor of particle physics, who is also a Christian, argues that religion is perfectly reconcilable with science. “The Believing Scientist: Essays on Science and Religion” by Stephen M. Barr (Eerdmans, 2016) is not always an easy read for those without a science background. References to such concepts as “probabilities in quantum mechanics,” “wave particle duality,” photoelectric effect,” “quanta,” and “gauge symmetries in electromagnetism” can be difficult to follow. But it’s worth the effort. The person of faith can take heart from the fact that his faith is completely compatible with what modern science tells us about physics, chemistry, and biology.

implacable conflict? In his new book, a professor of particle physics, who is also a Christian, argues that religion is perfectly reconcilable with science. “The Believing Scientist: Essays on Science and Religion” by Stephen M. Barr (Eerdmans, 2016) is not always an easy read for those without a science background. References to such concepts as “probabilities in quantum mechanics,” “wave particle duality,” photoelectric effect,” “quanta,” and “gauge symmetries in electromagnetism” can be difficult to follow. But it’s worth the effort. The person of faith can take heart from the fact that his faith is completely compatible with what modern science tells us about physics, chemistry, and biology.

Barr dismisses the narrowly literalist readings of Scriptures (like those cited to support the notion of a 6,000-year-old universe) that sometimes give religion a bad name. He also skewers the dogmatic atheism that masquerades as objective scientific argument against religion. Whether the target is ideologically-driven assumptions or the misinterpretation of scientific principles, Barr’s scientific detective work seeks to unravel big issues: “Where the ancient pagan went wrong is in seeing the supernatural everywhere in the world around him. Where the modern materialist goes wrong is in failing to see that which goes beyond physical nature in himself.” To those who contend that man is nothing but “a pack of neurons,” Barr counters with the aspects of the human mind – “such as consciousness, free will, and the very existence of a unitary self” – that cannot be accounted for by materialism. Distinguishing between primary and secondary causality, Barr sees nothing in evolution to contradict the workings of divine providence. The doctrine of providence tells us that that everything unfolds according to a divine plan: “It does not tell us the mix of law and chance, or of necessity and contingency, that God chose to use in his plan.”

By definition, nature works according to physical laws; overt divine intervention into nature can therefore only be a rare (miraculous) exception to the way the physical world around us works. But that tells us nothing about the intention and will behind those physical laws. What Barr finds more instructive, by the way of circumstantial evidence, is the astonishing “beauty, order, lawfulness, and harmony” that science keeps on discovering in the natural world. And a plethora of “anthropic coincidences” (in the way the laws of physics, chemistry, and biology work) undergird the existence of life as we know it. Change any of innumerable variables and we would not exist: “If certain parameters of particle physics were even slightly different… either stars would never have formed or biochemistry would not be possible.” Proof positive of divine design? No, but it is assuredly compatible with it. Likewise, the postulated ‘Big Bang’ may be consistent with religion’s message that the universe had a beginning; but Barr argues that the truth of the latter does not depend upon the ultimate validity of the former.

Barr shows how scientific materialism (the claim that everything can be reduced to the behavior of particles), physicalism, and reductionism – all of them legitimate principles in science – are often ideologically misapplied to deny the existence of what lies outside the natural world. And, for its part, scientific determinism has been circumscribed by science itself, courtesy of quantum mechanics, a physical system that yields probabilities, rather than definite outcomes produced by implacable physical forces.

Because Barr’s book is a collection of writings (essays and reviews of other books), there is some overlap and repetition of points and illustrations – like his useful analogy of a play: Is what happens within the play the result of its characters’ actions (horizontal causality) or because the playwright wrote the play that way (vertical causality)? Barr says both are true at the same time, without limiting our free will. He’s at his most engaging in his witty moments: Puncturing the scientific fallacy that all human behavior can be understood physically, Barr slyly comments that the author under his scrutiny “may know more than his brain, but according to [his] own theory, it is his brain that wrote the book…. I wonder how [his brain] wrote so knowledgeably about all the things [he] knows and his brain does not.” On the same point, Barr adds wryly that, “We should listen to great scientific minds because they are great scientific minds. However, when they begin to tell us that they really have no minds at all, we are entitled to ignore them.”

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

The Promise and its Fulfillment: Stories for Christmas

© By John Arkelian

‘The promise and its fulfillment’: That phrase is apt shorthand for what Christmas means to the person of faith. And those words are nicely exemplified in the book in which we found them –  “Christmas with Hot Apple Cider” (That’s Life! Communications, 2017). Edited by N.J. Lindquist, the anthology comprises 67 contributions by 55 Canadian writers. Most of the book’s selections are mini-memoirs, short accounts of real-life events. Those non-fiction accounts are interspersed with several fictional short stories and poems and one short play. Memoir or fiction, prose or verse, they are all variations on the theme of Christmas. It’s the fifth volume in the ‘Hot Apple Cider’ series, a series of anthologies that aim to uplift their readers with stories of “hope, faith, courage, and love.” Like the ‘Chicken Soup’ books, they’re good for the soul, rather like a spiritually-charged version of Reader’s Digest magazine’s first-person accounts. Their optimistic, uplifting tone is also reminiscent of “Ideals,” a magazine we haven’t seen in ages (but which still exists), right down to their monotone seasonal illustrations. They are also kin to the Ottawa Valley childhood stories of former CBC Radio raconteur Mary Cook.

“Christmas with Hot Apple Cider” (That’s Life! Communications, 2017). Edited by N.J. Lindquist, the anthology comprises 67 contributions by 55 Canadian writers. Most of the book’s selections are mini-memoirs, short accounts of real-life events. Those non-fiction accounts are interspersed with several fictional short stories and poems and one short play. Memoir or fiction, prose or verse, they are all variations on the theme of Christmas. It’s the fifth volume in the ‘Hot Apple Cider’ series, a series of anthologies that aim to uplift their readers with stories of “hope, faith, courage, and love.” Like the ‘Chicken Soup’ books, they’re good for the soul, rather like a spiritually-charged version of Reader’s Digest magazine’s first-person accounts. Their optimistic, uplifting tone is also reminiscent of “Ideals,” a magazine we haven’t seen in ages (but which still exists), right down to their monotone seasonal illustrations. They are also kin to the Ottawa Valley childhood stories of former CBC Radio raconteur Mary Cook.

The selections, from writers of varying degrees of experience, range from very serviceable to very good, and the common thread, besides the Christmas theme, is a prevalent tone of warm nostalgia. There’s a plain, simple, homespun quality to these accounts that’s quite endearing. And, we’re keen to read more by some of these authors. Several recount episodes from their childhood as immigrants to Canada. A postwar Dutch family who encounter the kindness of strangers deserves a book-length treatment. Another story authentically conjures the point of view of a child who has her first Christmas with her newly adoptive parents in 1948. The narrative voice in an account of a kitchen mishap is likewise very engaging. Helping others is a recurring theme, with stories that involve church outreach, an orphanage in West Africa, and a nursing home. Those afflicted with addiction, imprisonment, or the loss of a loved one discover hope. An umbrella becomes an impromptu Christmas tree; and a small town mystery set in coastal Nova Scotia makes us want to read the novel-length adventures of the same plucky protagonist. Out of the mouths of babes, a young child heals an elder’s sorrow. And a young woman far from home finds comfort in the spontaneous gift of a cheery apple.

There’s down-to-earth wisdom here: “We can’t do everything, but… we can do something. We can be the people others know they can count on.” A poem about the shepherds on the first Christmas has a nice turn of phrase, comparing the ennobling of man through the miracle of God becoming one of us to “a commoner called to court.” There’s a well-written Christmas ‘ghost’ story; an account of a full-sized Yule tree replaced by an indoor forest of eight small ones; a touching reflection on the absence of self-worth (“nothing on the outside, nothing on the inside”) and its remedy; an evocative poem about the sounds, smells, and tastes of Christmas; and an amusing account of the harder-than-it-looks task of assembling a bicycle on Christmas Eve. And there’s the peace that comes from rejoicing in the Promise and its Fulfillment.

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

The Spirituality of Wine:

Embracing Creation with Body and Soul

© By John Arkelian

As non-initiate into the world of wine, we approached Gisela  Kreglinger’s new book, “The Spirituality of Wine” (Eerdmans, 2016), with a combination of skepticism and uncertainty. Would a free-ranging examination of the spiritual utility of an intoxicant be persuasive? Would it hold the attention of a non-devotee of wine? The author, who grew up on a family winery in central Germany’s Franconia region, caught our interest with her Christian spiritualist perspective, one that “seeks to integrate faith into all spheres of life, including the material and the everyday.” Something there strikes a chord: life abundant includes celebrating the ‘good creation’ of “the generous and loving Creator who delights in bestowing gifts on his children, which make their hearts glad and their souls sing.” Ascetic strains of Christian theology emphasize the spiritual and the hereafter while neglecting the here and now. But we are both body and soul, and we are called upon to take joy (and find fellowship) in God’s creation: “The mark of a decidedly Christian spirituality is not a flight from creation but a faith-filled embrace of it.”

Kreglinger’s new book, “The Spirituality of Wine” (Eerdmans, 2016), with a combination of skepticism and uncertainty. Would a free-ranging examination of the spiritual utility of an intoxicant be persuasive? Would it hold the attention of a non-devotee of wine? The author, who grew up on a family winery in central Germany’s Franconia region, caught our interest with her Christian spiritualist perspective, one that “seeks to integrate faith into all spheres of life, including the material and the everyday.” Something there strikes a chord: life abundant includes celebrating the ‘good creation’ of “the generous and loving Creator who delights in bestowing gifts on his children, which make their hearts glad and their souls sing.” Ascetic strains of Christian theology emphasize the spiritual and the hereafter while neglecting the here and now. But we are both body and soul, and we are called upon to take joy (and find fellowship) in God’s creation: “The mark of a decidedly Christian spirituality is not a flight from creation but a faith-filled embrace of it.”

For Kreglinger, wine has had a long and important role in man’s embracing of creation. She cites Biblical chapter and verse to illustrate the association of natural bounty (including abundant grape vines) with the Promised Land; and she cites Christ’s first miracle – at the wedding feast in Cana, where He turns water into wine – as a key example of wine’s role in Biblical imagery and Christian celebration. The author sees wine as a sign of God’s blessing, and, through the Eucharist, as a tangible reminder that Christ stepped into ‘the divine winepress,’ shedding his blood for our sake. Taken in moderation, she says, wine is also a way to gladden the hearts of men through shared fellowship and feasting, as engagingly depicted in the film “Babette’s Feast.”

The book covers a great deal of territory, from the aforementioned theology of spirituality, to the cultural, economic, and religious history of wine, to the close connection between the expansion of Christianity and that of viticulture across Europe (the role on monasteries being pivotal in the latter regard). There are chapters on the philosophy of winemaking and one on the abuse of alcohol. Some of that material may be a tad esoteric for the general reader. It’s not immediately obvious who the intended reader of this book is meant to be: scholar or layman, wine aficionado or curious non-imbiber?

At moments, the author may wax over-lyrically about the benefits of “holy intoxication,” and she tends to reiterate points more often than may be necessary. Further, the book’s type-size is smaller than it comfortably ought to be. But, Kreglinger brings conviction, a sure command of her material, and an engaging writing style to what was, for this reader, unfamiliar terrain. One happy surprise came in the author’s brief preface, in which she alludes to her childhood on the winery: “I thought about the fields and vineyards, the sun and the rain… I thought about all the people who worked for us: their lives and sorrows…” It’s wonderfully evocative stuff that makes us yearn to read a memoir of the author’s childhood years.

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

Not in God’s Name

© By John Arkelian

“When religion turns men into murderers, God weeps…. Too often in the history of religion, people have killed in the name of the God of  life, waged war in the name of the God of peace, hated in the name of the God of love, and practiced cruelty in the name of the God of compassion.” The poisonous persistence of man’s inhumanity to man is inextricably rooted in our propensity, eagerness even, to see the world in terms of “Us” and “Them.” In “Not in God’s Name” (Schocken Books, 2015), Jonathan Sacks examines ‘altruistic evil,’ that is, “evil committed in a sacred cause, in the name of high ideals” which turns “ordinary people into cold-blooded murderers of schoolchildren.” Hatred motivated by religion may be the most pernicious: It encourages us to demonize the other and to do monstrous things in the name of the good.

life, waged war in the name of the God of peace, hated in the name of the God of love, and practiced cruelty in the name of the God of compassion.” The poisonous persistence of man’s inhumanity to man is inextricably rooted in our propensity, eagerness even, to see the world in terms of “Us” and “Them.” In “Not in God’s Name” (Schocken Books, 2015), Jonathan Sacks examines ‘altruistic evil,’ that is, “evil committed in a sacred cause, in the name of high ideals” which turns “ordinary people into cold-blooded murderers of schoolchildren.” Hatred motivated by religion may be the most pernicious: It encourages us to demonize the other and to do monstrous things in the name of the good.

As a Jewish rabbi and scholar, Sacks’ subject is three great monotheistic religions that claim common lineage to Abraham. It’s an apt canvas to reflect on the psychological and sociological origins of evil – and to propose ‘a theology of the Other,’ which posits that violence done in the name of religion is sacrilege and that we are instead called upon by our Creator to love not just our neighbor but also the stranger: “It is not difficult to love your neighbor as yourself because in many respects your neighbor is like yourself. He or she belongs to the same nation, the same culture, the same economy, the same political dispensation, the same fate of peace or war…. What is difficult is loving the stranger.”

Why are we so prone to fear and hate the stranger? Man’s loyalties originally attached to his blood kin, to his tribe, then to ever larger units, leading up to the state. The glue that bound such large number of people together was, historically, often religion. But, in the 20th century, we introduced modern substitutes – allegiance to a nation, race, or political ideology – secular idols that spawned the wretched, murderous likes of Nazi Germany and Communism. Today, we try to dampen down the craving for tribalistic identity by embracing either universalism (we are all part of the family of man) or individualism (which seeks to dethrone ‘the group’ entirely). Neither alternative provides satisfying answers to the questions “Who am I? Why am I here? How then shall I live?” But “radical, politicized religion” offers easy answers to those questions: hence its return with a vengeance, and its appeal to those who crave “identity and community.” We live in a time of rapid change; change brings disorientation and a sense of loss and fear that can easily turn into hate. And “the Internet… can make it contagious.”

Sacks’ book covers a great deal of territory, exploring topics like “dualism” (a pathological conviction that “we” are good and “they” are bad), scapegoating, and ‘mimetic desire,’ which is “wanting what someone else has because they have it.” And the theme of sibling rivalry looms large, with lengthy digressions into Old Testament accounts (Isaac & Ishmael, Jacob & Esau, Rachel & Leah, Joseph and his brothers, Cain & Abel) which seem to depict one sibling displacing another, but which actually have a profoundly deeper meaning: That we are to seek God not only in the faces of our neighbors (those who are like us) but also in the faces of strangers (those who are different from us). In this cause, Sacks says that the Jews have an advantage: They have ‘memory and history’ to remind them, “that we were once on the other side of the equation. We were once strangers: the oppressed, the victims…. In the midst of freedom we have to remind ourselves of what it feels like to be a slave.” The best path to seeing God (and ourselves) in the face of the purported Other is to have been the Other – enslaved, despised, and oppressed – ourselves: “for only one who knows what it feels like to be a victim can experience the change of heart… that prevents him from being a victimizer.” On this point, Sacks ignores the elephant in the room, with nary a mention of the State of Israel’s protracted armed occupation of Palestinians against their will: Despite their terrible suffering in the Holocaust, Jews are nevertheless themselves capable of oppressing the Other. And, so, the fires of mutual antagonism are fueled.

Sacks tackles these big subjects from a scholarly, occasionally somewhat esoteric, approach; but, even in the midst of his close theological interpretation of Biblical stories, he never loses our rapt attention: This is a deeply fascinating look at a subject that’s (sadly) in the news daily. Sacks’ message is one which all people of faith should embrace: “Civilizations are judged not by power but by their concern for the powerless; not by wealth but by how they treat the poor; not when they seek to become invulnerable but when they care for the vulnerable.” And we must never forget that “we are loved by God for what we are, not for what someone else is. We each [neighbor and stranger alike] have our own blessing.”

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist.

Copyright © 2016 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

The Moral Imperative of Revolt

© By John Arkelian

“I do not fight fascists because I will win. I fight fascists because they are fascists.” Jean-Paul Sartre coined that sentiment, and Chris Hedges embraces it in his new book, “Wages of Rebellion: The Moral Imperative of Revolt” (Knopf Canada, 2015). The Pulitzer Prize winning author is known for his clarion calls about a society in deep trouble. He persuasively argues that the West has fallen victim to what John Ralston Saul called “a corporate coup  d’etat in slow motion.” Covering everything from the surveillance state, the harsh suppression of dissidents, the flagrant subversion of the most fundamental human rights, our penchant for violence, and the insidious rise of neo-feudalism, Hedges’ book is a damning indictment of a society on the precipice – of totalitarianism and eventual collapse. At the heart of our troubles is the grip of capitalism as a “cultic religion” predicated on relentless consumption. Its ultimate goal is to serve the interests of an oligarchic elite, at the expense of everyone else. Our economy sheds jobs and stalls wages in a headlong rush to the bottom; and we reward financial speculation in lieu of useful production: “They make nothing. They only manipulate money.” There are clear signs that the environment, the global eco-system upon which we all depend for life is in trouble: We’re in the midst of first mass extinction in 66 million years. Our infrastructure is crumbling and we are unable to cope with environmental disasters: Events like Hurricane Sandy leave people with wrecked homes and shattered lives, as we “increasingly sacrifice the weak, the poor, and the destitute.”

d’etat in slow motion.” Covering everything from the surveillance state, the harsh suppression of dissidents, the flagrant subversion of the most fundamental human rights, our penchant for violence, and the insidious rise of neo-feudalism, Hedges’ book is a damning indictment of a society on the precipice – of totalitarianism and eventual collapse. At the heart of our troubles is the grip of capitalism as a “cultic religion” predicated on relentless consumption. Its ultimate goal is to serve the interests of an oligarchic elite, at the expense of everyone else. Our economy sheds jobs and stalls wages in a headlong rush to the bottom; and we reward financial speculation in lieu of useful production: “They make nothing. They only manipulate money.” There are clear signs that the environment, the global eco-system upon which we all depend for life is in trouble: We’re in the midst of first mass extinction in 66 million years. Our infrastructure is crumbling and we are unable to cope with environmental disasters: Events like Hurricane Sandy leave people with wrecked homes and shattered lives, as we “increasingly sacrifice the weak, the poor, and the destitute.”

Fairness, and, indeed, respect for constitutional first principles, have become flimsy illusions: “The pervasive security and surveillance state, which makes us the most watched, spied and eavesdropped upon, monitored, photographed, and controlled population in human history, is being employed against all who rebel.” Indeed, the state imposes draconian punishments against whistleblowers and anyone who challenges the state. Hedges says it’s nothing short of a war “against liberty, the freedom of the press, and democracy itself… The state can order the assassination of US citizens. It has abolished habeas corpus. It uses secret evidence to imprison dissidents… It employs the Espionage Act to criminalize those who expose abuses of power.”

Meanwhile corporate concentration makes a mockery of a well-informed electorate. In the US, the airwaves are controlled by about six corporations. And thoughtful, critical debate is hard to find. In its place, “Today charlatans and hucksters hold forth on the airwaves [the 2015-16 presidential primaries season has yielded a dire harvest of political hucksters and charlatans as candidates for the highest office in the land!], and intellectuals are ridiculed. Force and militarism, with their hyper-masculine ethic are celebrated… Culture and literacy… are replaced with noisy diversions, elaborate public spectacles, and empty clichés.” The underclass is criminalized and imprisoned. And fairness seems conspicuous by its absence: “Some 8,000 nonviolent Occupy protesters were arrested across the nation. [But] not banker or investor went to jail for causing the 2008 financial meltdown. The disparity in justice mirrored the disparity in incomes and the disparity in power.”

Hedges’ book carves a broad swath through diverse socio-political, cultural, and moral topics. There are brief case studies of the courageous few who have dared to defy authority – ranging from Edward Snowden’s alarming revelations about massive, unconstitutional intrusion by the state into the private communications of their citizens (all of their citizens), to a US Army pilot who stood between remaining Vietnamese civilians and those intent on killing them during the 1960 My Lai massacre, to the Zapatistas, the resistance movement in southern Mexico who used ‘poetry, art, and humor’ in their cause, to an attorney in the US, who is arguably a prisoner of conscience, who used her imprisonment to draw back the curtain on the harshness and arbitrariness of a privatized penal system, to whistleblowers like Assange and Manning. There is an interesting reflection on Herman Melville’s classic 1851 novel Moby Dick as an allegory for America, embodying a society’s ‘doomed voyage’ in its single-minded quest for wealth and domination over nature. There’s a nod to that great advocate for liberty, Thomas Paine, the American Revolutionary era political philosopher who exclaimed that, “He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression.” There is a cautionary note about the malign transformation of the internet from a supposed (and over-vaunted) “great emancipator” of the common man to a sinister “facilitator of totalitarianism” and tool of the powers that be.

Hedges makes a strong case that our society is in dire jeopardy, that the good of the many has been ignored for the benefit of the very few. While he sometimes sees through a doctrinaire, ideological lens, too broadly generalizing (he lumps the NRA, Tea Party, Republicans, and right-wing militias together under the allegedly shared fear of “crazed black hordes,” and he cavalierly describes the country’s episodic violence as “as American as cherry pie”), his underlying contention is a powerful one: We are in trouble, we are in danger of losing what remains of our liberty, and our incremental path to totalitarianism is a form of “radical evil” that the moral person must oppose by a non-violent uprising: “The person with moral courage defies the crowd, stands up as a solitary individual… and is disobedient to authority, even at the risk of his or her life, for a higher principle. And with moral courage comes persecution.”

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist.

Copyright © 2016 by John Arkelian.

***************************************************

Why Islam Needs a Reformation

© By John Arkelian

The religion known as Islam was founded almost fourteen centuries ago by a man who said that God’s message for mankind was  revealed to him. He set down those tenets in the Qur’an. The religious and political expansion of Islam began in Muhammad’s lifetime and accelerated after his death in 632 AD. Today, there are 7.3 billion people in the world, about 1.6 billion of whom are Muslims. The trouble is that the faith they follow has never left the 7th century – not one iota of it. And that’s a problem – not only for Muslims, but also for the rest of us. A new book argues that the root cause of Islamic extremism today is the doctrine of that religion itself.