The Yukon: Transforming the Human Spirit

© By John Arkelian

© Photography by Priska Wettstein

“Till a voice… on one everlasting whisper day and night repeated… ‘Something hidden: Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges – Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!’” (From “The Explorer” (1878) by Rudyard Kipling)

Something Hidden

I am among the giants. They loom below, immense, silent, and

“The Guardian” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

insouciant – their unbowed crowns cloaked in the whitest of ermine, their enormous shoulders cast of rock primeval. I have come to the world of winter. Even time grows large here, measured in glacial epochs. Deep frozen rivers of ice below ebb and flow beyond the ken of the human eye: And there is nothing human here, for as far as the eye can see. Yet this place, this heart of the Yukon, whispers to me: ‘Something hidden: Go and find it. Something lost behind the Ranges.’ Too often in life, we dig deep ruts for ourselves, sometimes tomb-deep. But here is a place of transformation, a place of reawakening, a place of rediscovering freedom, a place where the spirit quickens, a place in which one can find what is hidden and reclaim what is lost. For journeys here end in lovers meeting.

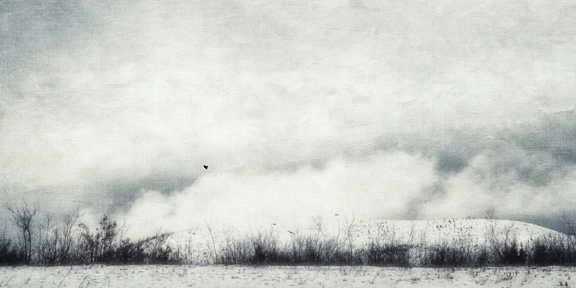

“Tombstone Valley after a Storm” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

Among the Giants

My odyssey begins in Whitehorse. I have long been drawn to the true North, and a glance in any direction is enough to raise shivers of delight. For the city is surrounded by snowcapped mountains. It is into those mountains that I embark on my first day, with a 150 minute drive due west and northwest on the Alaska Highway. Foothills are covered in forests of spruce. Ahead, the rounded peaks are soon juxtaposed with jagged ones: The latter are younger mountains – all sharp edges, they are still growing, bereft of the weathering and erosion brought by longer years. The closer I come to the mountains, the more enthralled I become by the view: It inspires awe. Here is Haines Junction, a picturesque village (it has

“Night Birds” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

nice little homes with a view – and how!) near the confluence of three parks – Kluane National Park, which is my ultimate (aerial) destination, a B.C. provincial park, and an Alaskan state park. The village is also home to a shop with a cute name: “The Little Green Apple” sells homemade banana bread as well as groceries. Then comes Kluane Lake. On a map, even a very big wall-sized map, it looks like little more than an afterthought in the immensity of the Yukon, but cartographical appearances can be deceiving. The lake goes on and on, seemingly without end. Glacier-fed, it has receded over the years, in part due to the redirecting (by natural causes) of one of its largest stream sources, which now carries its waters to the south.

Here’s Destruction Bay, which earned its name in 1942 when U.S.  military engineers building the Alaska Highway had their encampment blown away by a storm. Then I come to Burwash Landing and a small airfield in a meadow that’s home to two small airplanes. My pilot is John Ostashek of Rocking Star Adventures. As we step into the Cessna 172-P, a wag offers these words in lieu of safety tips: “If we crash, we die.” But crashing is never an option with such a sure hand at the wheel. There are two seats in front, with two more behind. I’m in the front passenger seat, with a bird’s eye view, but acutely conscious of the spare steering wheel and foot pedals are that in such close proximity to my long limbs. If sudden turbulence should prompt me to instinctively grab for something to hang onto, I hope I don’t reach for the wheel that’s an inch from my

military engineers building the Alaska Highway had their encampment blown away by a storm. Then I come to Burwash Landing and a small airfield in a meadow that’s home to two small airplanes. My pilot is John Ostashek of Rocking Star Adventures. As we step into the Cessna 172-P, a wag offers these words in lieu of safety tips: “If we crash, we die.” But crashing is never an option with such a sure hand at the wheel. There are two seats in front, with two more behind. I’m in the front passenger seat, with a bird’s eye view, but acutely conscious of the spare steering wheel and foot pedals are that in such close proximity to my long limbs. If sudden turbulence should prompt me to instinctively grab for something to hang onto, I hope I don’t reach for the wheel that’s an inch from my

“Storm over the Yukon River” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

thighs and send us into a death spiral. Our flight heads into Kluane National Park, and we enter the realm of the giants. It’s an ancient place, with nary a hint of anything human. And yet, it mesmerizes. It’s a world onto itself, indifferent to the more mundane places known to man. If you told me that I was making a transit of an alien world, I’d believe you. John, the son of a former Yukon premier, knows every peak and every glacier by name. It’s a guided tour of wonders. There are deep crevices in the ice below, peaks that touch the clouds, and enormous blocks of snow that have fallen off snowy promontories, looking for the world as though like they’ve been hand-cut into oversized cubes. The rock faces are grey – weathered old men who’ve lost none of their dignity and power. A later stretch

“Stripped to the Soul” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

resembles immense palisades: Forget about China’s Great Wall; here, nature’s wall has sheer vertical buttresses that rise to dizzying heights.

Early in the 90-minute flight, as I look straight ahead, it feels as if we are suspended in time and space. A downward glance (our maximum flying altitude is 11,500 feet) confirms that we are moving; but the view ahead seems as frozen as the wintry world that stretches to the horizon. A mountain looms directly ahead, and we are aimed squarely at its mid-section, as if on a kamikaze mission. The minutes pass and we seem no closer to the mountain we are approaching. It’s so big, and we’re so small, that the approach seems infinitely slow, as if time itself has become elastic

“Palace Grand Theatre” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

and has stretched beyond familiar limits.

At our furthest point on this aerial voyage, we reach Mount Logan, which, at 19,551 feet (5,959 meters), is the highest mountain in Canada (and the second highest in all of North America). We peek at it (or does it peek at us?) from behind a filmy veil of clouds. On the return circuit, we pass a younger glacier – its relatively tender years betrayed by its rough surface and dirty aspect: Like a child, it has been playing in the dirt, churning up the soil that lies deep below its frozen currents and bringing it to the surface. Outside the park proper lies a wildlife sanctuary, where rough roads climb the foothills to facilitate mining exploration, speaking to the unfortunate government decision to allow such activity in a place that more

“The Road to Midnight Dome” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

properly ought to be reserved to nature herself. When we land, I do my best imitation of an accent from Down East, fessing-up to feeling “some tense” during our aerial odyssey. It may have been a tad nerve-wracking for a relative newcomer to small aircraft; but, my, I’d have jumped at the chance to go again – then and there. Spectacular trumps scary every time! It was a mind-blowing, soul-stirring journey, and an oh-so-memorable way to begin my initiation into the land of transformation.

With the Huskies

Another day in the Yukon brings another adventure. This time, a short drive from Whitehorse, into nearer mountains, brings me to Ski High Wilderness Ranch, presided over by New Brunswick ex-pat

“The Old Post Office and the Palace Grand” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

Jocelyne LeBlanc. She knows every one of her 150 huskies by name, and she is justifiably indignant about the bad name some over-zealous documentary filmmakers have recently given the dog-mushing industry. Generalizing from the example of a few bad apples, they attributed the malign practices of a few to the entire industry. For her part, Jocelyne never engages it in the cost-cutting practice of ‘culling’ her dogs – by killing them at the end of the tourism season. Instead, she spends $10,000 in one week on “spring cleaning” (for spaying the female dogs and other veterinary costs). The first stop for visitors is a log cabin heated by a wood-burning stove. There, I am outfitted from head to toe. There are sturdy, no-nonsense snow boots, heavy canvas pants (I don the

“Roam Free” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

laced boots first, by mistake, but no matter – the pant legs unzip and fit right over the oversized footwear), winter parkas, heavy-duty canvas mitts, and wool toques. The clothes make the man, right? Then, it’s off to dogs, where one of Jocelyne’s instructors, Steve, tells the handful of entranced visitors how to stand astride the metal sled rails and control the team of four dogs which will shortly be our responsibility. The key lesson is: Don’t spare the brake. The dogs are impatient to run full-out; it’s up to the driver to pace them, lest they collapse from exhaustion during the 60 minute run. The dogs’ welfare is taken very seriously around here. What Steve doesn’t realize, at first, is that one couple is from Brazil: The man speaks almost no English; his wife speaks some and intermittently

“Quest for Solitude” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

translates bits of the instructions to hubby. Not surprisingly, the lesson of the brakes is lost in translation.

The dogs are eager to be selected, some giving voice to howls in their excitement, as befits the Yukon’s legendary ‘call of the wild.’ An ailing knee persuades me to opt for Plan B, riding behind Jocelyne on a big snowmobile to keep tabs on the novice mushers. And we’re off! Though the woods, across a road, and onto a frozen lake – Fish Lake, to be precise. It may be April, but it feels like winter out here, with the bracingly cold air biting my face. As a child of cooler climes, I am in my element. The vista of snow-clad mountains (Mt. Granger and McIntyre among them) encircling this massive alpine lake causes my heart to skip a beat. Afterwards, guests are treated

“I Only Hear Silence” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

to hot chocolate in a Mongolian yurt, with a take-away bag containing a homemade cookie and the best sweetened popcorn I’ve ever tasted.

Around Town

At the lower altitudes where Whitehorse sits, the snow is gone in mid-April. It’s a drab time of year to make the acquaintance of any new place: The pure white of winter has not yet been replaced by summer’s greensward. The time between those seasons can be visually dreary, especially in urban areas. It’s no different here (in town), and my first impression of the city is of an unprepossessing place. But first impressions can be deceiving. There are restaurants here that equal anything in the metropolises of the south. Every night’s supper is a memorable treat, with impressive cuisine. At

“Fireweed Seeds” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

Giorgio’s Cuccine, I have chicken linguini, with generous strips of some of the most delectable grilled chicken I’ve ever tasted. G&P Steakhouse and Pizza is no pizza joint; but they sure make a mean thick-crust pizza, giving my favorite pizza (in distant Port Hope, Ontario) a run for its money. Last, but not least, The Wheelhouse has a riverside view, sternwheeler ship’s décor, a pair of talented jazz instrumentalists on bass and keyboard, and a first-rate steak (not to mention a melt in your mouth lemon meringue dessert). When I tell the personable owner (a former Yukon cabinet minister) that I’m visiting from “the Eastern Reaches,” he adopts a convincing Irish brogue. “Not that far east,” I say in amused response.

My hotel, the Westmark Whitehorse Hotel, once a default

“Embracing Solitude” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

destination for cruise ship excursions from the Alaskan Panhandle, looks a tad dated and drab from the outside (and in its lobby), but the rooms are clean and perfectly satisfactory. To my delight, I discover that Whitehorse is home to my new favorite bookstore. Mac’s Fireweed Books on Main Street stays open late nightly, and it has an array of books, magazines (including “Foreign Affairs,” which is mighty hard to find in much bigger stores in my corner of the far-off metropolis), and stationary that speaks to the good taste and discernment of whomever stocks its shelves. The obliging staff even retrieves an itemized bill for me, after the fact, from their computerized register. (Though I didn’t get to visit it, Whitehorse is also home to Well-Read Books, a big and very popular used

“Tombstone Park” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

bookstore.) Shoppers will not want to miss Horwood’s Mall on Main Street. A group of buildings have been converted inside to house 40 upscale boutiques, whose wares include imported wine, specialty cheeses, art, and fashion. A couple of blocks away, Arts Underground is home to exhibitions, classes, and events. By all accounts, the Yukon has, per capita, the biggest arts scene in Canada. I am pleased to find that it’s like Iceland and Newfoundland in that respect – all three are isolated places, far removed from larger population centers, in which people celebrate creativity in art, music, film, and literature. One man in the know tells me that people here value the land, its animals, human relationships, and working together. “The place reduces stress levels,” he says. In the

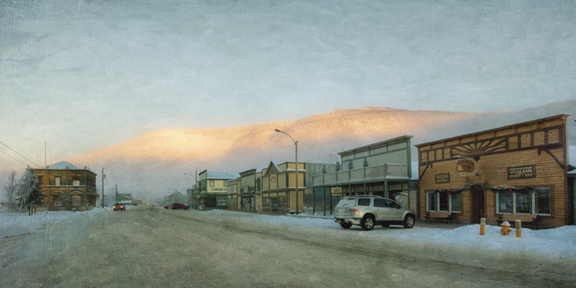

“Dawson City” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

Yukon, community counts; and arts and culture are the glue that binds communities together. There’s a nice college campus in Whitehorse; an arts center that’s home, among many other things, to an annual film festival; and a modern recreational center.

Whitehorse is bordered by the Yukon River. Permanently docked there is the S.S. Klondike, a sternwheeler ship that’s now a national historic site. And history is on effective display at two museums in town. The Yukon Beringia Interpretive Center is a modern first-rate museum dedicated to the story of the Ice Age land bridge between Siberia and North America – the route humans took to reach this hemisphere. Replica mammoth bones loom over visitors, while the skeletal remains of a large taloned creature look like a

“Dawson Front Street at Minus 42 Degrees” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

fearsome monster from “Alien.” In fact, the owner of those lethal looking claws was a more benign giant sloth. Situated downtown, the MacBride Museum of Yukon History occupies an older building but contains much of interest. A display of gold from Klondike creeks shows how the shape and size of bits of that precious metal ranged from dust to small nuggets, according to its precise place of origin. A display of native implements has everything from sealskin mukluks, to an ‘ulu’ (an Inuit woman’s curved knife), to a parka made from the feathers of 70 ducks, and artfully beaded moccasins. One large room is devoted to an extensive display of taxidermy: Countless birds and animals found in the Yukon have been stuffed and posed here. Among the roll-call are lynx, wolves, grizzly bears, polar

“Drifting” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

bears, caribou, elk, cougar, mountain goats, snowy owls, bald eagles, moose, ermine, and otters. I’m alone in the gallery and the effect is startlingly lifelike. Another room is devoted to the 1,523 mile long Alaskan Highway, constructed during the Second World War in response to feared Japanese incursions against the west coast. In 1942, 11,000 American army engineers and 16,000 civilian workers built the highway from Dawson Creek, B.C. to Fairbanks, Alaska in a mere eight months. Another gallery has evocative recreations of late 19th century Yukon shops and offices, among them, a public health nurse’s examining room, an early movie theater (the Orpheum), the Bennett Sun newspaper printing press room, a barbershop complete with peppermint pole, a dockside display, a

“Midnight Meadow” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

general store (with everything from canned food to old Underwood typewriters), and a tavern. I longed to see these recreations given a much bigger space and manned with costumed re-enactors. At the modern Yukon Tourism and Culture Information Center, I’m envious of a beautiful theater that’s note-perfect for a film festival I run back home. During my tour of museums, I come across words that stay with me: “The Yukon pulls the cotton out of your ears and pulls the blinds away from your eyes.”

The Desert Dunes

Driving southwest from Whitehorse, I espy a black bear cub at the side of the road: It darts into the forest at my vehicle’s approach. Regrettably, other wildlife keeps a low profile during my visit, save the ubiquitous ravens, which play a prominent role in the territory’s

“A Short Moment” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

mythology. There’s a gob-smacking surprise in store for me at the side of the road – in the form of towering sand dunes that roll off into the distance like a Sahara of the North, bounded by mountains. The Carcross Desert used to be a lake bed ages ago: I have to resist the urge to trek across its dunes like a latter-day Lawrence of Arabia. A little further down the highway is the village of Carcross, which takes its name, originally, from Caribou Crossing. The very picture of quaintness, everything here is scaled back to half-size (or smaller): Churches look to be intended for congregations of a dozen parishioners; and a line of brand new single-room art studios is bordered by bright totem poles. A heritage hotel, which is under painstakingly protracted restoration, was once home to a

“Memories of Spring” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

foul-mouthed parrot of local renown. As one observer comments, it’s ‘a funky little town’ that slumbers in the winter, reawakening each summer to greet the tourists drawn by its artisans, its alpine beauty, its world famous mountain biking trail, and its terminus for the scenic White Pass heritage railway from Skagway, Alaska. And, though it is covered in ice and snow at present, the aptly named Emerald Lake is close at hand. In the surrounding forests, IKEA once hired locals to collect certain kinds of pine cones, so that furniture-maker could plant Canadian pine trees back in Sweden. Morel mushrooms are another local cottage industry, with jealously guarded picking patches in the wilds.

Northward to Dawson

The 70-minute flight from Whitehorse to Dawson is a welcome  change from the steerage class ‘service’ afforded by Air Canada and its ilk. In stark contrast to the big airlines, the Yukon’s Air North makes its passengers feel welcome – and valued. Seating is first come, first served when you board the plane (a Hawker Siddely 748). And they feed you, for no extra charge: A generous piece of fresh apple strudel is my choice on the flight north. On the return trip, several days later, I get a sandwich, a cookie, and an Easter egg – as well as a friendly greeting from the stewardess who recognizes me from the inbound flight! Welcome warning signs, these, that I am about to arrive in one of the most congenial places I have ever visited.

change from the steerage class ‘service’ afforded by Air Canada and its ilk. In stark contrast to the big airlines, the Yukon’s Air North makes its passengers feel welcome – and valued. Seating is first come, first served when you board the plane (a Hawker Siddely 748). And they feed you, for no extra charge: A generous piece of fresh apple strudel is my choice on the flight north. On the return trip, several days later, I get a sandwich, a cookie, and an Easter egg – as well as a friendly greeting from the stewardess who recognizes me from the inbound flight! Welcome warning signs, these, that I am about to arrive in one of the most congenial places I have ever visited.

Dawson City is a mere five or ten minutes from its small airport. It

“Half Dog” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

is bounded on one side by the Yukon River, on another by the Klondike River, and on a third by a mountain that culminates in the 2,911 feet (887 meters) high Midnight Dome. Arriving here is like moving back through time. The clapboard buildings with painted names (Dawson City General Store, Klondike Kate’s, Maximilian’s Emporium, the Eldorado Hotel, and Diamond Tooth Gerties’s), combined with the wooden plank boardwalks, and the scarcity of cars makes this feel like the Old West, except it’s the Old Northwest. Home now to only about 1,000 residents, it once had 40,000 as the Yukon’s former capital and the epicenter of the gold rush. I was warned about the mud. At this time of year, at least, it’s really more of a compacted sandy clay. The roads and sidewalks aren’t paved here, because the heaving permafrost would buckle pavement in no time flat. With early spring run-off, there’s too much water at the end of some blocks to make using the boardwalks practical. But it’s so quiet here, with so little vehicular traffic, that I do what many others do: Day or night, I walk right down the middle of the unpaved streets. It’s the driest place to walk, and I acquire only a very slight soil coating on the soles of my shoes.

It’s love at first sight at the Aurora Inn, my home away from home for my stay in Dawson. Elegant, artful, and comfortable, the place is full of original art, pine, and tasteful touches at every turn. There’s not one wrong-note here: Casual elegance is evident everywhere you look. I am greeted by the personable new owners Steve and Tracy Nordick (who have taken over from Swiss émigré Priska Wettstein and her husband) and shown to a suite that I’ll be mighty loath to leave when my stay ends. The gorgeous dining room is a pleasure to visit. And someone here sure can cook: (That goes for the daytime chef Emilie and for her German-speaking evening counterpart Christian.) Every item I order from the menu is a sheer pleasure – not least the generous helping of warm brownies, a veritable chocolaty explosion, to which I succumb for three nights running.

A Place for Free Spirits

The dining room’s two delightful staffers – Aly from Arizona and Freddie (Frédérique) from Montreal – instantly feel like long-lost friends. Sure, one can have pleasant enough table conversation with those waiting on tables anywhere. But, there’s something much more authentic and meaningful going on in Dawson. People stand close (without being uncomfortably close); they make eye contact; and the talk is anything but superficial. People here want to engage, to make meaningful contact. It’s tangible, manifest, and intoxicating. There’s something about the people here, a common theme I encounter again and again. Nearly everyone I meet comes from somewhere else. They either were or aspired to be free spirits before they came here And they perceive, as I do, that the Yukon in general (and Dawson in particular) is a place for free spirits, a place for reinventing oneself, for finding what is lost within. And it is irresistible.

Being in Dawson means switching gears after my hectic itinerary in Whitehorse. Here, I’m without fixed plans, other than cinematic ones. I just gear-down, meet people, and savor the setting. I’m told that there are more women in town than men. That is surprising: I’d have expected it to be the other way around. Am I imagining things, or does the gender imbalance lend an ineffable frisson to casual encounters, a subtle, almost sexual, charge to even the most innocent interactions?

A Festival of Film under the Northern Lights

Dawson is home to the cabins of the poet Robert Service and the writer Jack London, who said, “I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet. The proper function of man is to live, not to exist.” Those words hold a powerful resonance for me in this place. The childhood home of writer Pierre Berton is also located here. But, more to my purposes, this community is home to the Dawson City International Short Film Festival, a four-day celebration of short films from far and wide, an international film festival only a few hours drive from the Arctic Circle that’s now in its 18th year! It has been presided over for ten of those years by Ontario transplant Dan Sokolowski. This year’s line-up comprises 85 short films and one feature film. The remarkable thing is how many entries come not just from the North generally, but also from right here in this small community. Maybe not everyone Dawson is a devotee of the arts, but they sure have more than their fair share of arts practitioners and arts aficionados. Forget about Toronto’s TIFF, community support for Dawson’s film festival is enthusiastic and instantly palpable. And there’s no caste system or hierarchies here. Everyone – from visiting “VIPs” (somehow I’m categorized as one!) to regular filmgoers – mix and mingle without distinction. It’s casual and unpretentious – with that wonderful authenticity that’s so integral to Dawson. And there’s a first-rate array of films on hand.

Opening night at the festival has its sole feature-length film. And it couldn’t be a better choice. “Dawson City: Frozen in Time” is at once a documentary history of the town, of the Klondike gold rush, and of the era of silent films. At its heart lies the story of 500 silent films used as landfill long ago and recovered from the Dawson permafrost (which preserved them) many decades later. At a reception, Suzanne Crocker, a director of one of the shorts, asks if I’d seen her film. Its name doesn’t instantly ring a bell, so she offers a reminder about its content. I still don’t recognize it. ‘Well, it couldn’t have made much of an impression,’ she says with a good-natured laugh. At the same reception, I meet Marina, who coincidentally hails (and recently at that) from the same corner of the Greater Toronto Area that I currently call home and who used to work for a media acquaintance of mine. I chat with Al Cushing, the retired director of the Yukon Arts Center, and Andrew Connors who presides over the Available Light Film Festival, both visiting from Whitehorse, and with Jeanie Dendys, the Yukon’s new Minister of Culture and Tourism. (She has a background in the justice sector, and I ask her hopefully if Dawson could use a resident lawyer. Since none are currently in evidence, I have visions of declaring myself, without fear of contradiction, to be ‘the best lawyer in town!’) And I find very congenial company at the hours-long screenings at the Klondike Institute of Art and Culture (KIAC) in the lovely person of Corinna, an émigré from Germany who was seduced by the Yukon’s siren call. She resolutely distilled her worldly goods to what was essential and made the long-distance move – a fearless plunge into the possibility of transformation that I find compelling.

The Land of the Ten P.M. Sun

When I leave the festival venue on opening night, it is 10:10 pm, and, to my bewilderment, it is broad daylight. Yes, Dawson is far enough north to be in ‘the land of the midnight sun’ for some weeks each summer (and in the land of everlasting night for some weeks each winter). And, it’s small enough that you can see the Aurora Borealis right in town, if the elusive northern lights deign to make an appearance, that is. (Alas, they do not on the occasions when my gaze seeks the sky overhead.) The walk back to the inn, perhaps five blocks, is an evocative one: At this time of year, Dawson is like a ghost town, a ghost town that’s been lifted intact from a bygone era and plunked down in ours, unchanged.

Reluctant Partings

There are yet more chance meetings on my final morning in Dawson, more testimonials from those captured by the special magic of the Yukon. At the Aurora Inn, there are retired professionals from Whitehorse in town for the film festival: Al Fozard and his wife, Rod and Heather (transplanted Maritimers and retired lawyers both), and Wayne Tuck (a retired engineer who’s traveling with his wife). Then, at Dawson’s little airport, the two young women on duty laughingly engage with the three waiting passengers – there’s just me, and Jonathan Ganter, who came here from Australia to run his own heavy duty diesel company, and his lady friend, Angela Ritchie, who runs her own adventure camping business in Whistler, B.C.

It’s time to go, but, my goodness, I’m loath to do so. Something has awakened in me here, something that won’t easily be suppressed. Something hidden behind the Ranges has been found and cherished – something transformative, something impossible to ignore: “I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you. I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh.” (Ezekiel 36:26) For the Yukon will transform you, beyond hope, beyond expectation. That is its power – and its irresistible allure.

******************

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist. Among his eclectic pursuits, he has represented Canada abroad as a diplomat, advised the federal cabinet as an international lawyer, conducted criminal prosecutions as a federal Crown attorney, served as a professor of media law, been a candidate for Parliament, and directed an international film festival. He is the founding editor of Artsforum Magazine.

Priska Wettstein is one of the Yukon’s most talented photographers. (She and her husband are also the former owners of Dawson’s delightful Aurora Inn.) To see more of her evocatively beautiful work, visit: https://www.priskawettstein.com/

Text copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

Photographs copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein.

Editor’s Note: Instead of illustrating our feature about the Yukon with conventional landscape photography, we are proud to showcase the breathtakingly beautiful work of Swiss-born Dawson resident Priska Wettstein. Her impressionistic images are wonderfully evocative, capturing the moods of Dawson and its environs with an artistry and subtlety akin to watercolor paintings.

Corrigendum: The two uncaptioned photographs above are: (1) “Wander in the Fog” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein; and (2) “Gossip” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein.

See “Movies under the Midnight Sun,” our coverage of the Dawson City International Short Film Festival at: https://artsforum.ca/film/featured-film-reviews

**********************************************

“In the Land of Ice and Fire”

© By John Arkelian

© Photography by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

I have been to the Uttermost North, a place to which I have long been drawn. I swam in a lagoon the color of blue milk with drifting mists floating above its surface, felt my heart leap in joy at the sight of mighty breakers crashing on a remote black beach at the top of the world, trod upon an ancient glacier,

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

traversed moonscapes of breathtaking beauty, walked up a small mountain, and visited an islet by boat for the lighting of a peace tower that hurled beams of blue light into the obsidian infinity of the night sky. The place was Iceland, and it has left me with a ceaseless longing that only a return can quell.

It begins with the shuttle ride from Keflavik Airport (once home to a NATO

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

airbase) to the city of Reykjavik, whose environs are home to two-thirds of this island nation’s 317,900 inhabitants. Dawn is breaking in the east and the dark blue mountains ahead are backlit by a sky that’s streaked with pink and mauve and yellow and blue. It’s a dramatic backdrop for an unearthly landscape. Lava fields surround the shuttle in all directions. The earth’s very bones have erupted – jagged and roughhewn – from the surface, and they give bare, silent testament to the age-old, relentless workings of time and the elements. Here, the palette is in shades of brown and grey, with flaxen wisps of grassy vegetation. Iceland’s celebrated Nobel-laureate writer Halldor

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

Laxness captured the sense of this place in these few words: “And there where the glacier touches the sky, the land ceases to be earthly.” (“Og thar sem jakulinn ber vid loft haettir landid ad vera jardneski.”) Yet man – so small, so fragile, so ephemeral – has touched even this strange terrain: Giant statues hewn from stone stand vigil on the crest of hills in the near distance (the uneven piled-rock bases upon which they rest bring to mind the inukshuks of Canada’s Arctic), like the trolls of national folklore, gazing out to sea as they await the return the return of the fisherfolk who make their living there. It’s a treeless, almost lunar, landscape, until we reach the city. Reykjavik is a clean and orderly place, Scandinavian in character, save that

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

its houses are clad in stucco and aluminum siding rather than wood. Splashes of bright color reminiscent of St. John’s accent the prevailing shades of light grey and ivory.

Although I reach the modern Hilton Reykjavik Nordica hotel, where my room offers an expansive view of city, harbor, and volcanic mountains, in time for breakfast, I forego it (and a bed that beckons to my jetlagged senses) in favor of a 30-minute hike to the city center. The shopping district has arranged itself around Laugavegur street, but my ramble takes me to a simple hot dog stand, “Baejavins bestu,” that’s beloved by locals. Sure enough, there’s

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

already a queue for the stand’s specialty – hot dogs made from lamb and topped with honey-flavored mustard.

Mid-afternoon brings more serious business, in the form of an awards ceremony at the city’s elegant Hofdi house. Built in 1909, this art nouveau manse hosted the October 1986 summit of Presidents Reagan and Gorbachev, a meeting that marked the beginning of the end of the Cold War. Today, it’s the venue for the “Lennon-Oko Grant for Peace,” a biennial award set up by Yoko Ono to honor the memory of the late John Lennon. Today’s recipients include a documentary filmmaker (Josh Fox, for his Sundance award-winning film “Gasland”); a food safety advocate (Barbara Kowalcyk, who was propelled into activism by the loss of her young son to an E-coli infection); an author who writes about the nexus between nature and culture; and the writer Alice Walker, for her opposition to Israel’s blockade of Gaza. The third recipient, Michael Pollan, is the best speaker (and the most audible, in a ceremony that’s hampered by poor acoustics and even poorer sight-lines). He reminds us that while “voting with your fork may seem like a small

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

gesture,” a better world starts when we all live as if our every action matters. He exhorts us to embrace “a pure, crazy act of imagination.” And that’s at the heart of what’s happening in Reykjavik over the next few days. The awards coincide with Lennon’s 70th birthday, and the theme is inspired by his iconic ballad, “Imagine.” Who better to get things rolling at the ceremony, then, than the city’s newly-minted mayor Jon Gnarr. It’s hard to hear him, but his reputation comes through loud and clear. He’s the prototype of the

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

un-politician – a humorist (he put smiley-faces on downtown “walk” signals) who entered the political fray in the aftermath of the traumatic political, economic, and social maelstrom that recently struck Iceland with volcanic force. His mission? To inspire people to trust their leaders again: “Utopia has no passports, only people.” Imagine, indeed!

I share supper with fellow journalists at Vox, the upscale restaurant at my

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

hotel. The meal consists of roast lamb, root vegetables, and a hot-flavored soup akin to minestrone. Then, it’s off to the harbor for a ferry-ride to nearby Videy Island. A couple thousand people walk under the starlight to the Imagine Peace Tower. It’s a white circular stone well into which the words “Imagine Peace” have been carved in 25 languages. Then, all of a sudden, intense beams of blue light shoot forth from the well, piercing the dark sky above. It’s a touching moment, and a children’s choir is on hand with a candlelit rendition of the Beatles’ “Across the Universe” and Icelandic

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

folksongs. They’re hard to see (or hear) from my vantage point, but the event’s heart is certainly in the right place.

Would that I could say the same for a concert held later on in a large theater on the mainland. Perhaps the vocal stylings of Yoko Ono are an acquired taste? If so, I remain steadfastly among the uninitiated. Ono does a fair impersonation of a screaming banshee, and the deafening din that ensues is an all-out assault on the senses. I flee the auditorium after two unbearable

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

“songs,” pointless exercises in cacophony that bear no more resemblance to “music” than do howling cats or the shrieking inmates of Bedlam. I can still hear what follows (alas!) from my self-imposed exile in the lobby; and it seems that my disdain for the lamentable spectacle on stage is far from the prevailing view; judging by the thunderous applause, good music must be in the ear of the beholder.

The next day brings a group walking tour downtown. The first stop is the Reykjavik Art Museum, whose director shows off the surreal collages of

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

native son Erro. Then, it’s on to the “Reykjavik 871 +/- 2 Settlement Exhibition”, which combines archaeological excavations and high-tech holograms to propel visitors eleven centuries back in time to the days of the first Viking settlers. Lunch also entails stepping back in time, insofar as the setting is Laekjarbrekka, the city’s most traditional restaurant — a place that occupies a charming 1834 house and offers up such culinary delights as

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

lobster soup. I try on parkas at 66 degrees North (an Icelandic maker of quality outerwear that’s rapidly attracting a clientele abroad) and see the people’s square that witnessed uncharacteristic violence sparked by the country’s recent visit to the economic abyss. Supper at the Seafood Cellar (Sjavarkallarinn) consists of exotic delicacies that would make Poseidon himself envious. Our group of journalists share a mouth-watering feast of platter after platter of mixed appetizers, main courses, and desserts (one of the latter is presented with fog cascading down the sides of the bowl) chosen by chef Ragnar Omarsson. The delectable offerings appease our band of

Copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir

hungry sea-gods.

The following day is devoted to a ten-hour sightseeing excursion in the countryside. With an embarrassment of riches on offer, it’s hard to choose just one; but I settle on the South Shore Excursion, and it has delights aplenty, starting with stark lava fields that stretch on and on as far as the eye can see, punctuated only by what I’m convinced must be the mountains of the moon – geology that’s more consistent with another planet than with anything recognizably earthly. We pass the 1666-meter Eyjafjallajokull — a volcano topped by a glacier that’s quiescent now but was active enough a few short months ago to disrupt air traffic across half of Europe with voluminous clouds of ash. Ever practical, Icelanders are scooping up the black cinders it deposited over countless acres and using it to surface roads and sidewalks (they even export the stuff!). One of our first stops is the Skogar Folk Museum, where an eccentric old guide with a lively twinkle in his eyes, plays a few notes on the “pangspil,” a stringed instrument from France that migrated to these more northerly climes in the Middle Ages, demonstrates wool-spinning, and leads us through turf-houses that date back to 1830. Today’s journey takes in two separate waterfalls. First up is the broad, 60-meter high Skogafoss, which is said to be one of Iceland’s most impressive; and, truth be told, it’s more than up to the task of giving Niagara a run for its money. I test my endurance (and my mixed feelings about heights) by walking most of the way up the adjacent small mountain. Next comes the narrower, but (at 65-meters) equally impressive Seljalandsfoss. You can walk behind this waterfall, but I’m too entranced by the view from out front to bother. Then we enter a valley to encounter the Myrdalsjokull glacier. The air is palpably cooler as we approach, but not cool enough to spare this ancient river of ice its helpless retreat in the face of global warming. The easternmost point of the day-trip is the village of Vik — nestled, almost Swiss-style, amidst grass-covered mountains dotted with sheep and distinctive Icelandic horses. The former supply the wool that’s used in Vik’s knitting factory.

The highlight of the day is the black beach of Reynisfjara, a place that eminently deserves its title as one of the ten most beautiful beaches in the world. My heart leaps in my chest at the raw elemental power of this place. Something irresistible impels me to where sea thunderously meets land, even as the tour guide’s warning cries of “Careful! Be Careful!” echo distantly behind me. On my left, the mountain of Reynisfjall rears itself out of the sea, giving sanctuary on its staggering heights to thousands of seabirds. Further down the beach, to the west, the sheer promontory of Dryrholaey looms (at 120-meters high) at the edge of the sea: A large natural sea gate has been eroded through its solid rock — large enough for a small boat (or a stunt plane) to pass through. And there’s Reynisdrangar, columns of basalt jutting from the sea, which, according to folklore, are all that remains of two trolls who were dragging a three-masted ship to land when they were caught by the dawn and turned to stone along with their prize. Here, I find what the Icelandic poet Steinn Steinar wrote about: “We have been searching since the dawn of time / Across the desert of time and space.” (“Ver leitum fra orofi alda / Um eydimork tima og rums.”)

I find such a place again the following day — my last in Iceland on this visit — at the country’s celebrated Blue Lagoon. The place does not disappoint: Its alien landscape stretches as far as the eye can see — lava rock again, piled as high as a tall man and lightly sprinkled with moss and lichens in the palest shades of yellow-green. Ahead, and on each side, steam drifts up from pools of surface water. A sleek, ultramodern spa looks out upon an immense lagoon: It is milky blue, buoyant, and warm — and half-shrouded in drifting mist. I melt in its embrace, half-expecting a mermaid to swim languorously up to me (some passing bathing beauties have to suffice). Wooden walkways and curved foot-bridges surround and intersect the lagoon’s coves, and they are patrolled at intervals by staff in neon-colored slickers with hoods. Could they be the keepers, and we bathers the exhibits, at some alien menagerie? For, surely, I am adrift in a lake on another world. One thing I know, this place is heavenly — and not to be missed.

I wish I could say the same for the journey home. Whoever said getting there is half the fun obviously hasn’t flown lately. The flying sardine cans we call airlines have configured their interiors with the expectation that their passengers have left their legs at home. Unfortunately, I brought mine with me — and I find myself with nowhere to put them. Things go from badly cramped to utterly intolerable when the passenger in front of me puts her chair back. It stays there, a mere six inches from my nose, for the duration. It’s a miserable way to endure five-and-a-quarter hours. But, despite that ordeal, I’d line up tomorrow to return to the wild beating heart of the North we call Iceland!

John Arkelian is an award-winning journalist and author based near Toronto.

Rebekka Gudleifsdottir is one of Iceland’s most talented photographers. To see more examples of her breathtakingly beautiful work, visit: http://www.rebekkagudleifs.com

Text copyright © 2010 by John Arkelian.

Photos copyright © 2012 by Rebekka Gudleifsdottir.

********************************************************************

“Child of Sea and Sky: A Nova Scotian Odyssey”

© By John Arkelian

© Photography by Warren Gordon

From the journal of a non-linear traveller…

To begin, I should confess that I am spellbound by this place. It’s a place of

Presqu’ile, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

sea foam and the wind, of roaring surfs and rugged, rock-hewn coasts, of quaint coves and forests that stretch to the horizon. It’s an exhilarating place of grand vistas and dramatic skies, with a capital city that’s as steeped in culture as it is in our colonial past. It’s a place that feels like home, and it keeps beckoning me back.

I. Riding on the whale’s back…

The Cabot Trail is an organic thing – playful, daring, and exuberant as it

Beinn Bhreagh, Baddeck, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

swoops and turns, plunges and climbs, clinging to looming mountainsides, lingering by rocky shores, darting into immense woods, and boldly descending at break-neck angles toward the glistening sea. To traverse the trail is to ride the whale’s back, thrilling all the while at its wild life coursing beneath you. My embarkation point for the 300-kilometer trail is the town of

Beinn Bhreagh, Baddeck, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

Baddeck, where the attractive Inverary Resort provides a comfortable respite after my rather hasty three-and-a-half hour drive from Halifax. I’m pleased to find the Lakeside Cafe open at the edge of Cape Breton Island’s inland sea, the Bras d’Or, though it’s dark by the time I sit down to eat. On the trail the next morning, near the Acadian town of Cheticamp, a sudden,

Lake O’Law, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

ill-considered impulse to seek a photo opportunity on the other side of the road, propels me between an off-road pothole and an unimpressed oncoming motorist. There aren’t many fellow travellers at this time of year – a benefit for those who appreciate nature best in its pristine solitude – but neither have the leaves changed colors yet. It’s only the beginning of October, and

Cap Rouge, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

autumn’s finery is still a week or more away. I miss the colors, but the rolling mountains, glorious vistas, and ever-present sea offer ample compensation. This place is lovely – whether clad in plain green or bedecked in red, yellow, and vermilion.

II. At the end of the world…

Can a place, as well as a person, be a kindred spirit? With two-thirds of the

Cap Rouge, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

Cabot Trail behind me, I find such a place near Ingonish. There, the Middle Head Peninsula points like an impossibly long, rocky finger into the deep blue heart of the sea. Buttressed by steep cliffs, with the pounding surf as its moat, this fortress of rock and forest is my heart’s true home – a sanctuary of beauty and tranquility that befits the idylls of a king. Perched atop this sea-girdled

MacKenzie Mountain, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

promontory of dreams, the Keltic Lodge is a gleaming white castle of wood, commanding the heights like its resident eagles, its long green lawns adorned with bright wooden chairs in red, white, yellow, and blue, as birches and spruce stand vigil beyond. This place exhilarates and comforts at the same time. It is a destination – for travellers and seekers alike – not the mere

Aspy Bay, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

stop-over I had imagined it to be. I sit by the cliffs, enraptured by the fjord-like scene, the brisk autumn wind, and the sky ablaze with dusk’s red glow, too enchanted to quit my post till the sun slips behind the mountains to the west.

I take my suppers in the main lodge’s lounge – an elegant room of palatial

Aspy Bay, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

dimensions, full of pillars, fireplaces, and intimate conversation areas. One evening, I chat, over an idiosyncratic Highland club sandwich (in which traditional ingredients are joined by a fried egg!), with a charming couple from Tel Aviv, as a pair of talented singer/guitarists (Cyril McPhee & Rob Maclean) perform in the background. The next night brings different

Meat Cove, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

company (a personable young woman from Finland), different cuisine (a striploin steak sandwich with mushrooms and onion rings on fococia bread, garnished with garlic, and soup inventively blended from chicken and apple), and a different performer (Dublin’s own Fran Doyle). A sprawling formal dining room hosts the daily breakfast buffet – it’s a veritable cornucopia, the

Ingonish, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

likes of which I’ve never seen – and I quickly acquire a taste for the fruit smoothies.

I devote one afternoon to hiking the Middle Head trail. I’m a brisk walker, but the moderately exacting route to the tip of the peninsula takes almost an hour one way. Negotiating the inclines and avoiding the tree roots account for its

Ingonish Beach, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

toll of moderate exertion. At times, the forest is dense enough overhead to cast an almost nocturnal shade; at times, the path hugs the cliffs’ edge, high above the crashing surf. And then I come to the world’s end, where a plaque proclaims “The end of land… Cloud, ocean, and sun. Empty. Waiting for time. Like the beginning.” Here I keep a long, solitary vigil, perched on a rock

North Bay Beach, Ingonish, Cape Breton Island — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

at land’s end, high above the ocean, whose relentless surf reverberates below. My vantage point is a small grassy meadow, peppered in places with tiny violet flowers, a silent place, save for the sound of the sea and the whisper of the wind. My companions are the cool wind, warm sun, and silent forest of white spruce behind me – an outpost visited only by rare passing

Canso Causeway, connecting Cape Breton Island to mainland Nova Scotia — Copyright © 2013 by Warren Gordon

butterflies, chickadees, and gliding ravens. Far across the bay, white sails appear against the looming mass of Cape Smokey, whose intimidating heights I must traverse tomorrow. By late afternoon, I get a closer look at those heights as I wander the length and breadth of Ingonish Beach, a place that’s lonely now, but doubtless teeming with bathers in warmer months,

III. Percussionists galore, theater on the wing (and on the edge), and a tiny, perfect artist…

How does that song go? “We’ve got rhythm, who could ask for anything more?” Well, there’s rhythm to spare in the Halifax musical extravaganza called Drum! The exclamation mark’s there for a reason in this full-throttle tour de force by percussionists. They are joined by fiddlers, dancers, and singers in a celebration of the cultures of four peoples who settled this land – the aboriginal Mi’kmaq, the Acadians, the Celts, and black settlers from the Thirteen Colonies and Caribbean. The result is a New World spin on Riverdance – a dazzling, virtuoso display of musical moxie that sets the adrenaline coursing. It’s enough to raise the roof off the corner of the sprawling warehouse where it’s staged, and therein lies its only flaw – it’s too deafeningly loud for such a confined space. Turn down the volume, please!

Halifax combines European charm with a pleasing informality. Strolling its hilly downtown and gentrified harbor-front evokes the city’s past as an important colonial center in a maritime empire. And, this delightful setting is fertile ground for theater, art, and music. It’s always a pleasure to return to the Neptune Theatre. This time, they’ve got a solid production of To Kill A Mockingbird. Comparisons to the classic 1962 film version of Harper Lee’s beloved novel are inevitable, and, truth be told, nothing can hope to match that film – save the book itself. However, the stage version does stand up well on its own merits. C. David Johnson (who is perhaps best known from CBC-TV’s popular series Street Legal) lacks the gravitas of Gregory Peck (though, to be fair, who doesn’t?), but he’s competent in the role. For her part, Arielle Legere soars in the pivotal role of his tomboyish daughter, Scout. The set design deserves a nod, too: its stylized streetscape accommodates several houses in close quarters, while the wooden-look of the courtroom set – colored in monotones – suggests a stage within a stage, for the real-life drama we call trials. For director Ted Dykstra, the story is about courage in the face of persecution, and that’s a story that never tires in the telling. Next door, in the Neptune’s Studio Theatre, there’s a very different play about the nature of power, truth, and fear. Produced by One Light Theatre and directed by Shahin Sayadi, Death of Yazdgerd is an edgy, contemplative reflection on ‘who is a king, and who is a poor miller?’ Its setting may be Persia in 651 A.D., but its themes (and innovative staging) are as modern as can be. The one-act play juxtaposes the mighty (“a king whose flag is fear and army is loneliness”) with the seemingly humble, with surprising results.

More surprises are in store a few blocks away at the must-see Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. As luck would have it, they’re hosting four prominent shows during my stay. There are 204 works on loan from Boston – everything from Pompeian wall paintings to an Egyptian mummy – spanning 6,000 years of antiquity. There’s a fascinating exhibit of large conceptual drawings by Christo – the fellow who’s fond of draping whole bridges in fabric and planting orchards of over-sized umbrellas along freeways. There’s a 4,000-year old collection of Asian ceramics, and there’s Itukiagatta, an impressive display of Inuit sculpture from the National Gallery of Canada. And, that’s not even mentioning the 11,000 works in the gallery’s permanent collection, among them the tiny (12′ x 12′) shingle house (relocated from Digby) that belonged to the diminutive folk artist Maud Lewis. Every imaginable surface and object contained therein is adorned with Lewis’ sprightly art.

I divide my time in Halifax between the Four Points by Sheraton – which is modern and convenient, though lacking its own restaurant, a view (from my side of the building, anyway), and, temporarily, peace and quiet in the morning (thanks to some nearby construction) – and the Halliburton House Inn. Attractively renovated row-houses, the latter have delightfully intimate patios nestled under overhanging trees – it’s the perfect place for lingering over coffee and conversation come the evening. Less appealing are its parking arrangements in an alleyway that’s so cramped it’s sure to put claustrophobics to flight. Happily, nothing’s amiss at the bustling Triangle Ale House, where good-natured staff whisk away an order of a Reuben sandwich that fails to suit and cheerfully replace it with a just-right repast of fish and chips.

IV. Botanical haunts of the very rich; and a one-pub crawl…

Change is in the air today. Some of it is welcome, like the appearance of colorful foliage on the 77-minute drive from Halifax to Wolfville; some less so, like the arrival of hot, humid weather. But the Bay of Fundy is a place of change, where the world’s highest tides rise and fall in a twice-circadian rhythm. I get a sense of their magnitude when I cross the Corwallis River: At low tide there’s just a wide (and deep) sandy canal where the river should be. For its part, time itself seems to change when I check into the Blomidon Inn. Built in 1887 by a man with his own fleet of merchant ships, this Victorian mansion is chock-a-block with teak and mahogany – on wainscots, mantels, and staircases – as well as marble fireplaces, gilt mirrors, and antique furnishings. It’s like stepping into the past, though the resident ghost gives me a wide berth. There’s not a lot happening in town during my stay, and time doesn’t permit an excursion to either the bay proper or to nearby Look-Off Point; but, I enjoy the tasteful selection of art (including works by Alex Colville) at the private Harvest Gallery, while I chat with its Ontario ex-pat proprietress. Then it’s time to test my mettle at Paddy’s Brew Pub, where I follow an order of haddock and chips with a generously proportioned piece of what they quite accurately dub “very high pie.” It’s high alright, and I’m sailing low in the water after finishing it.

Then, as dusk approaches, it’s on to the ivy-leaguish, heavily-treed campus of Acadia University. My destination is the new K.C. Irving Environmental Sciences Centre and Harriet Irving Botanical Gardens – a gift from the Maritimes’ wealthy industrialist family. I’d be happy to call the elegant building home – its classical Georgian architecture is all red brick and white trim, set off by pillars, square lines, and arched windows. Inside, it’s a place of vaulted ceilings, bright natural light, and expansive greenhouses. Outdoors is just as inviting, with a six-acre botanical retreat reproducing an eclectic array of natural habitats – from sand barrens to marsh – and a path that leads me through woods and alongside a gurgling brook.

V. Renaissance herons; kaleidoscopes; mud pie; and a visit to the land of the not so recently departed…

I cut across the waist of the province to get from one coast to the other – and find autumn’s colors in full blaze at last. After pausing to hang my hat at the sprawling Oak Island Resort at water’s edge near the village of Western Shore, it’s on to my ancestral haunts in Mahone Bay for dilled gazpacho soup, buttermilk bisquits, and the chocolatey explosion known as “mud pie” at my favorite eatery, the Innlet Cafe. I stop next door, at Simple Things, to enjoy hand-crafted art like Corey Brown’s wonderful glass kaleidoscopes (which are truly toys for grown-ups), Delia & Ray Wills’ pewter starfish and tidal-pool bowls, and Kate Church’s fanciful airborne puppets – sculptural creations that look like something out of Cirque du Soleil. That same sense of whimsy is abroad in town, too. Every year around this time, it’s populated by a myriad of scarecrows in every guise imaginable: A pair of human-sized herons are adorned in purple-hued finery like a Renaissance lord and lady, while a gazebo at harbor’s edge is festooned with a gaggle of circus clowns. Third time proves lucky in my quest to discover the obscure cemetery that’s home to some of my kith and kin, folk who settled in these parts over 250 years ago. And, I stop to look at watercolors by Carol Whitcombe at the Spirit Song Gallery in her home. She’s not in, but I have a pleasant chat with her husband, John, a British immigrant, who served with colonial forces in Palestine and spent time in New Mexico before finding a home here: “Canada was like home from day one; I never even think of England now.” My final stop is the town of Lunenburg, a world heritage site, and a place that’s a window into our past. I chat with a pair of fellow bibliophiles at Elizabeth’s Books (one of whom hails from my birthplace in Ontario) before wandering the hushed, evocative streets. With fog gathering ominously in the distance, I head back to the resort, encountering a deer along the way.

The next day, I take the scenic coastal route back to Halifax, passing a picture-perfect cove between Aspotgan and North West Cove; struggling (in vain) to locate an acquaintance without her street address in the one-horse village of Boutilier’s Point; and visiting a fog-bound Peggy’s Cove, where tiny water droplets soak every exposed surface in a matter of minutes, and where my rental car’s heating vents are pressed into service as an impromptu hairdryer. Then, before I know it, it’s time to leave this place of sea and sky behind. But its hold on me is as strong as ever, and I’ll be back.

John Arkelian is an an award-winning journalist and author.

Warren Gordon is one of Nova Scotia’s most accomplished photographers and the author of several books of photographs about Cape Breton Island. As is evident here, his landscape photography is a wonder to behold. Visit Warren Gordon at: http://gordonphoto.com/

Text copyright © 2013 by John Arkelian.

Photography © 2013 by Warren Gordon.

Editors’ note: Versions of the foregoing article have appeared in the hard-copy edition of Artsforum Magazine and in Canada’s biggest newspaper, The Toronto Star. This is the first appearance of these words with Warren Gordon’s breathtaking images. (July 2013)

********************************************************************

“In Old Québec”

© By John Arkelian

T.S. Eliot’s “time present and time past” coexist in the vibrant place called Old Québec. Its cobbled streets are lined with stone buildings that date back 400 years, but they’re as full of life today as ever they were, positively coursing with the tides of present-day commerce and culture.

Chateau Frontenac overlooking boulevard Champlain (photo by Yves Tessier of Tessima for Quebec City Tourism).

I make the trip by train, a mode of transport I haven’t tried for many years. It takes nine hours from the outskirts of Toronto, but the time passes more quickly than I expect, thanks to congenial company and business-class service. The meals and legroom remind me of what flying used to be like, before airlines began, in miserly fashion, to begrudge their customers space and even a morsel of nourishment. Québec City’s train station is the most elegant one I’ve ever seen, a pleasing marriage of old and new. And the short ride to my hotel confirms that first glowing impression of the city. This is the closest one can be to Europe without leaving the New World: The narrow streets and heritage buildings of Vieux-Québec have a character and charm that gratify the senses and stir the imagination.

Chateau Frontenac and the fortifications (photo by Luc-Antoine Couturier for Quebec City Tourism).

My choice of inns, the cozy Auberge du Trésor, couldn’t be better situated. Only a small green park, the Place d’Armes, stands between my windows and the storied façade of the Château Frontenac. Upper Town lies at hand, and the aptly named Breakneck Stairs (l’Escalier Casse-Cou) to Lower Town are just a half-block away. So, too, is the long promenade atop the escarpment that overlooks the St. Lawrence and offers breathtaking vistas of the port (immense ocean-going cruise ships are docked there), the river, and the Appalachian Mountains to the south. After I check in and make the acquaintance of the inn’s delightful desk clerks Dina and Eliane (one of whom will later observe that the three of us chatter like magpies), I devote the evening to a ramble through the atmospheric streets of Upper Town. It’s an historic labyrinth: Pick a direction, any direction bounded by Old Quebec’s 4.6 km of walls (it’s the only Western Hemisphere city north of Mexico to have retained its fortifications), and you can’t go far wrong. I’m lost in a reverie as I stroll streetscapes out of a colonial past – a past that has endured here as a palpable, living thing. When I reach the shopping district centered on rue St. Jean, I visit book stores and a multi-storied

The past lives on in Lower Town (photo by Yves Tessier of Tessima for Quebec City Tourism).

marvel devoted exclusively to all things Christmas.

Day Two starts with a breakfast meeting with a personable representative of the city’s tourism department. I’m astonished at the rich artistic and cultural life he describes: At different times of the year, the place is abuzz with live theater and music, with festivals drawing performers and audiences from far and near. Then, I’m off for a four-hour guided tour with the good-humored Caroline Lafrance. She’s a walking font of information and anecdotes, and she’s forgiving of her charge’s inconveniently unsettled tummy – a condition that threatens to turn the morning into a tour of the city’s public washrooms. Speaking of which, there are some very nice ones, with bronze roofs yet, in Battlefield Park, where the pivotal clash between two European empires settled the fate of Canada. As a child, Caroline’s father told her that ‘there’s not enough room in Old Quebec to wag a dog’s tail.’ One thing is certain: Attractions are thick on the ground here. There’s something to see or do at every turn. In a unique coming-to-terms with the past, two martial adversaries – Generals Montcalm and Wolfe – are commemorated on the same monument. There’s the grand Château Frontenac poised atop the cliffs like a manse transported from France’s Loire valley – an edifice that took over 30 years (1893-1925) to erect and which has been under perpetual renovation ever since. There’s the Séminaire du Québec, where Laval University (the oldest French-speaking university in North America) was born. Today, a group of schoolboys practice football in its gleaming white courtyard, their shouts demonstrating the space’s noted acoustics.

A short drive out of the city takes us to Montmorency waterfall. At 83.5 meters, it is 30 meters higher than Niagara; and, I test my mettle on the gondola that takes visitors up the mountain. In winter, people come here from all over the world to climb the frozen ice. Returning to the city, we espy the Île d’Orléans, whose rich soil and natural beauty make it the city’s garden and getaway destination.

Sidewalk cafe in Quartier Petit-Champlain at night (photo by Yves Tessier of Tessima for Quebec City Tourism).

Perhaps saving best for last, we end up in Lower Town, whose Petit Champlain and Sous-le-Fort streets are among the oldest in the New World. They’re chockablock with stone and brick buildings, with brightly colored dormers and roofs; and they’re home to an irresistible array of boutiques and restaurants, with fanciful names like “La Lapin Sauté” (“The Rabbit Who Jumped”) and “Dingue de Tois” (“Crazy about You”), and equally idiosyncratic exterior decorations, like dozens of lime green and orange shoes beating a path along a wall high off the ground. In the fall, the district’s overflowing flowerpots are joined by seasonal fare, like pumpkins carved with the face on top so the stem can serve as a nose. Here a three-story high mural gives a visual history of the port, with everyday folk going about their business (like a woman pulling her husband out of a tavern by the ear); and there an even taller trompe l’oeil montage light-heatedly combines historical figures and modern-day sightseers. The oldest spot in the city is Place Royale, a cobbled square with a bust of the French king, Louis XIV. If the 498 steps back up the towering rocky cliff-face are too daunting after a long day, a glass-walled funicular elevator provides less onerous egress.

A fire across the lane forces a temporary evacuation of my inn, which obliges me to visit the classy Grand Théâtre de Québec in mufti that evening. Somehow, the touring garb of the day doesn’t suit this elegant setting; and, I belatedly realize that the surtitles projected above Opera de Québec’s presentation of Verdi’s “Aida” are en français, rather than my accustomed English. But I find that I can follow the dialogue; and I wouldn’t have missed the gorgeous sets and costumes — whatever my linguistic and sartorial limitations!

Verdi’s “Aida” at the Grand Theatre de Quebec (photo by Louise Leblanc, courtesy of Opera de Quebec).

Day Three is devoted to a closer exploration of Upper Town and a short jaunt by a tiny (and free) electric “écolobus” to the Musée des Beaux Arts at the far side of the sprawling Battlefield Park. The striking gallery building is the result of an international design competition. It is home during my visit to “The Nude in Modern Canadian Art 1920-1950,” an eclectic exhibition of paintings, drawings, and sculpture which present the nude female body in poses both demur and unabashed, idealized and matter-of-fact. For the most part, these works eschew notions of ‘ideal beauty’ in favor of a more realistic (if less glamorous) aesthetic; but there are excursions into the metaphorical, too, with works like Jean Dallaire’s “The Dancer and Death.”

That evening, serendipity brings me to the Palais Montcalm — a concert hall in front of which people are already skating on a rink that has anticipated winter by several weeks — for the infectious blend of intensely impassioned music and dance known as “Paco Peňa,” after its chief musician. Lithe, sinuous, sculpted bodies are aswirl in a kaleidoscope of motion and color. This flamenco troupe from Spain is worth traveling across the continent to behold — mesmerizing and fiercely passionate, they are positively ablaze, rousing the packed house to ovation after standing ovation. Only the flamenco vocals prove to be an acquired taste; for the rest, it is the most dramatic combination of music and dance I’ve seen in years.

Flamenco music and dance from Spain at Quebec City’s Palais Montcalm (courtesy of Paco Pena)

Day Four brings an unseasonably early snow and sleet storm. Nearby indoor attractions, like “Québec Experience’s” 3-D audio-visual retelling of the city’s history, “Musée du Fort’s” 400-square-foot narrated scale model of the city circa 1759, and browsing in shops (like a leather-goods heaven) are a way to avoid the inclement weather. So, too, is a visit to Holy Trinity Anglican Cathedral, with its pews made from imported English oak. As I’m there, I join in a morning

An evening of Bach at Quebec’s St. Roch Church (courtesy of the Quebec Festival of Sacred Music).

communion service and make the acquaintance of congregants from Ontario, Vermont, Britain, and Germany – people who visited Quebec and, like me, fell in love with the place. They stayed — and I’d like to! I have supper with a friend that night at a popular Italian restaurant called Portofino, the highlight of which is sorbet packed into a coconut half-shell. Then, it’s off by taxi to St. Roch Church, in a trendy district “outside the walls,” for a performance, bathed in purple light, of Bach’s “Mass in B-Minor” — the opening concert of the Québec Festival of Sacred Music — where I chat with an adult immersion student from B.C. who is sitting nearby.

Avenue Saint-Denis in winter: Mon pays ce n’est pas un pays, c’est l’hiver (photo by Luc-Antoine Couturier for Quebec City Tourism).

Later, reluctant to call it a night, I brave the now frozen snow to walk the Terrace Dufferin along the escarpment’s edge one last time with a friend, discussing life and this magical place that’s teeming with… what? With a fecundity of the spirit — the creativity, energy, and sheer astonishing diversity of things to see and do that make this place a jewel in Canada’s national crown.

John Arkelian is a journalist and author based near Toronto.

Copyright © 2010 by John Arkelian.

******************************************************************

China: A Society in Transition –

Between Traditions and Modernity

© By Belinda Martschinke

© by Belinda Martschinke

If I had known what challenges would be lying ahead, would I still have come to visit China? The answer is yes, definitely. Never has a country fascinated me more — with all its contradictions and its fast pace of development. It is the diversity of the experiences which exert the incomparable attraction. You might encounter yourself in the most modern shopping centre, faced with all manner of items of Western luxury and quality, while, on the street around the corner, you might find yourself walking through a hutong, one of the residential areas from decades ago which are such an immense clash with the high-rise-condominiums plastering most urban areas.

© by Belinda Martschinke

Speaking about China as one coherent entity is impossible. There is no way to compare the futuristic living conditions of modern-day Shanghai and Beijing to the countryside with its remote villages which are so far removed from consumerism. One doesn’t have to go far to be exposed to these contradictions: In Beijing’s embassy district, up to the Wanfujing area, glass facades of office and shopping buildings are right next to slum-like traditional dwellings, where you’ll find people brushing their teeth in the street or old men playing cards or mah-jong while chickens walk around their feet.

What are the Chinese like — all 1.3 billion of them? Well, the generic urban Chinese lives a quite anonymous life, trying to ensure his daily survival. Not surprisingly, manners are often neglected, which becomes apparent when people try to squeeze into the already filled subway or when someone snatches a taxi away from a pregnant woman waiting in the rain. Who could resent a Chinese lady holding her baby on her arm when she charges a Westerner fifty percent more than a local person? But as soon as you get to know the Chinese a little bit closer and establish some first-hand contact, you’ll be surprised at how much openness, helpfulness, caring, and loyalty you will encounter.

© by Belinda Martschinke

A true understanding of Chinese culture is unthinkable without an understanding of their language. Being able to communicate — and to understand subtle expressions and tones — is critical for getting access to the hearts and minds of the Chinese. It might take some years, if not a lifetime, to fully understand the meaning and diversity of Chinese characters, tones, and colloquial expressions. Chinese grammar is very logical and surprisingly simple: Verbs don’t change their form; past, present, and future tenses do not exist in the verbs; singular and plural are the same; questions and answers are built according to the same word order. But you’ll need a strong persistence to avoid despairing in the face of the four different tones (which entail different sounds, different meanings, and different characters for one syllable), as well as stamina when learning how to write Hanzi — Chinese characters which follow a prescribed stroke order. Every Chinese will revolt if you draw the fourth and fifth stroke of a character in reverse order. We might argue that it doesn’t matter in which order you write it as long as you finish with the same character; but, for the Chinese, this is taboo. It may help to know that Chinese children undergo year after year of persistent training in reading and writing characters; the more characters they master, the more their parents will love them. The art of writing is a direct path to parental attention and affection.

The hunger for education has grown to an extreme in recent years. Never before has a generation been pushed so strongly into acquiring as much knowledge and as many capabilities as possible. Sending kids to English learning centres cannot start early enough. After ten hours of kindergarten, which already covers arts, sports, language, maths, and social interaction, five-year-olds are busier than business managers when attending their evening programme, filled with additional language, dancing, singing, or musical instrument classes. The average four-year-old finds his/her well-deserved nightly sleep no earlier than eleven o’clock.

© by Belinda Martschinke

Chinese always offer a smile and a helping hand when you need it most, and they will warmly welcome you into their lives. During a dinner at a Chinese home or restaurant, your Chinese host will spoil you with the finest dishes and make sure that both the table and you are filled super-abundantly.

Chinese landscapes are as diverse as its people and traditions. Apart from the pervasive pollution in urban and industrial hubs, the Chinese landscape is among the finest. Stunning mountain sceneries like Huang Shan or Hua Shan will take your breath away in the early morning sunrise above the clouds. So will the impact of thousands of years of cultural heritage as you stroll through the terracotta warriors and horses of the Qin dynasty. Be it the vast grasslands and deserts of Inner Mongolia, the karst hills winding along the Li River between Guilin and Yangshuo, or the dragon-bone rice terraces in the north of Guanxi province, the beauty of nature will cast its spell upon you. And don’t miss the little villages along your way, where you’ll experience a more traditional life style, with fisherman, workers carrying tree trunks on their shoulders, or farmers guiding water buffaloes across little stone bridges.

© by Belinda Martschinke

China’s particular charm comes from its rapidly progressing, diverse society, its breath-taking natural beauty, and its ancient cultural heritage. If you are open towards all these experiences, this country will be open to you; and, in the end, you’ll be as apt to love this “Middle Kingdom,” Zhongguo, as much as I do.

© by Belinda Martschinke

Belinda Martschinke is a graduate student in business and an avid traveller.

Text and photographs © 2011 by Belinda Martschinke.

© by Belinda Martschinke