Silver Screens in the Wilderness

© By John Arkelian

“Face this world. Learn its ways, watch it, be careful of too hasty guesses at its meaning. In the end you will find clues to it all.” (H.G. Wells, “The

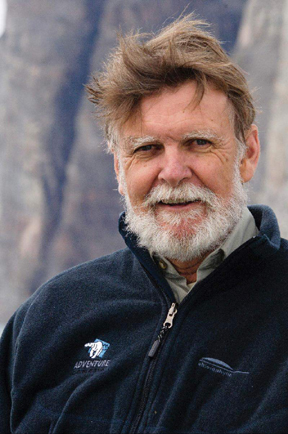

Keith Stata at the threshold of the Highlands Cinema in Kinmount, Ontario. Photo © 2024 by Scott Ramsay, courtesy of Door Knocker Media.

Time Machine,” 1895)

In a 1908 collection of essays titled “New Worlds for Old,” the English writer H.G. Wells wrote that “We all have our time machines, don’t we? Those that take us back are memories… And those that carry us forward are dreams.” With an impressive written output in disciplines as diverse as history, social commentary, and fiction, Wells remains best known today as the ‘father of science fiction.’ Seventy years after Wells wrote those words, a man in the most unlikely of places took up the mantle as a purveyor of both memories and dreams, instinctively divining that, for most of us, movies are our time machines, our chief and irreplaceable gateway to dreams and memories, and our window onto the wider world. How better, after all, to learn the world’s ways than to vicariously experience other times, other places, and other ways of living through the stories projected onto the silver screen?

As a child, Keith Stata was fascinated by the 1960 film “The Time Machine” (which won an Oscar for its Special Effects long before computer-generated imagery made such things ubiquitous). It remains one of his favorite films today (along with everything from “Cloud Atlas” to “Brother Sun, Sister Moon,” “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” “Soldier Blue,” and “Atlantis, the Lost Continent”). In 1978, he began building what amounts to his own figurative time machine on 22 acres of property situated at the junction of Haliburton, Kawartha Lakes, and Peterbough County. In its heyday, Kinmount, Ontario was home to a thriving lumber industry. Nowadays, the small municipality is home to a mere 300 souls. Yet, the surrounding expanse of forests and lakes draws thousands to its cottages, resorts, and campsites during the spring through early fall.

“If you build it, they will come.” That’s what an unseen voice tells Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella in 1989’s “Field of Dreams.” The protagonist of that film, and of the novel by Canada’s W.P. Kinsella upon which it was based, feels simultaneously inspired and compelled to build a baseball field in the midst of his corn crop. In Stata’s case, the compulsion and inspiration was to erect silver screens in the wilderness in the belief that if he built them, people would come. It would be memories and dreams that would draw them:

“Ray, people will come Ray. They’ll come to Iowa for reasons they can’t even fathom. They’ll turn up your driveway not knowing for sure why

Keith Stata in one of the five theaters at the Highlands Cinema in Kinmount, Ontario. Photo © 2024 by Scott Ramsay, courtesy of Door Knocker Media.

they’re doing it. They’ll arrive at your door as innocent as children, longing for the past. Of course, we won’t mind if you look around, you’ll say. It’s only $20 per person. They’ll pass over the money without even thinking about it: for it is money they have and peace they lack. And they’ll walk out to the bleachers; sit in shirtsleeves on a perfect afternoon. They’ll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the baselines, where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they’ll watch the game and it’ll be as if they dipped themselves in magic waters. The memories will be so thick they’ll have to brush them away from their faces. People will come Ray.”

Baseball was the catalyst in Kinsella’s story; movies are the driving force in Stata’s. His Highlands Cinema started with a single theater with 58 seats and grew over the years to a homemade multiplex of five theaters, the biggest seating 200, the smallest 75. In total, there are 550 seats catering to locals and summer season folk alike. First-run Hollywood features are on-screen (though Stata had to fight to get access to first-run shows), while the complex’s extensive corridors are home to an impressive collection of pop-culture memorabilia arranged by decades and meant to be instantly evocative of their time. It’s a virtual museum of popular culture, with artifacts worthy of the Smithsonian, among them, hundreds of film projectors, including one from the late, lamented Cinesphere at Toronto’s Ontario Place and antiques (like an 1890 Lumière) from the very earliest days of motion pictures.

Stata’s goal has always been to “create an experience that you’d remember” by getting people of all ages to “go to some place they’ve never been and have a magical experience.” Their immediate destination, of course, is his array of indoor silver screens in the boundless forest; but, in a figurative sense, the destinations are as diverse as the movies his patrons experience. They came in throngs see blockbusters like “Jurassic Park,” “Twister,” and “Pirates of the Caribbean.” An Imperial stormtrooper in white armor was on hand for the premiere of “Solo.” And there is no dilettante programming here or one-off single screenings: every film plays for at least a week. Meanwhile, at the snack bar, patrons flock to the popcorn, whose secret ingredient is coconut oil: ‘Accept no substitutes,’ say devotees, among them the wildlife (some 40 raccoons, two bears, solitary deer and skunks, and a veritable legion of squirrels) who feast on the nightly leftovers. Stata must have had the same objective (of opening a gateway to enchantment), if only

Courtesy of Keith Stata and the Highlands Cinema.

unconsciously, from his youngest years, when, at age six, he unspooled condensed versions of movies on 8mm film in his family’s woodshed.

The Highlands Cinema grosses $400,000 in an average year, with the bulk of that earned in a mere nine weeks out of its five-and-a-half months operating time. When asked if he ever considered going year-round, Stata retorts, “Do I look crazy?” In the winter, the audience have decamped to warmer climes; the steep hills are a slippery obstacle; the sewers are apt to freeze; and Stata needs time to decompress: “There’s a limit to how much I can do anymore… I didn’t count on getting old.” Well, at 77, not exactly ‘old,’ but not as young as he used to be. For such a small community, the cinema is a significant employer — with 11 at its peak (though not all at once) and about half that these days. But the global pandemic known as COVID, with its mandatory shutdowns, posed a mortal danger to the enterprise. Income fell to nil, ‘social distancing’ was impossible in intimately sized amphitheaters, and the financial picture looked very bleak. Selling off some of the land to keep things afloat fell afoul of bureaucratic red-tape, and at one point Stata responded with a caustic billboard worthy of the 2017 film “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.” Stata is one of those forthright people whom you never need to ask twice about what he really thinks. For instance, about the irresponsible hunters who trespass on his land and whose reckless aim has potshots flying dangerously close to his head, Stata says he’s sorely tempted to shoot back.

Stata was born and bred in the environs of Kinmount. Work took him to Toronto, but he soon concluded that the Big Smoke wasn’t for him. Back on familiar turf, he ran a construction business for 26 years, which gave him the know-how and resources to build his cinema. A career in making movies didn’t seem to be a viable option; but showing them certainly became one. His work in construction included a sideline in dismantling old cinemas across North America, places whose flotsam and jetsam provided the raw material that make up the very bones and sinews of the Highlands — the chairs (all of them reupholstered), moldings, doors, and assorted architectural features hail from all over cinematic creation — making the structure itself a monument to the art of cinema. There are artful touches here with intricate ceiling fixtures and stained glass; but there’s also an occasional touch reminiscent of Ed Mirvish’s “Honest Ed’s” store in Toronto with its dryly humorous indoor signage and sly bits of deliberate near-kitsch.

Regrettably, there are no plans for the facility’s long-term survival, no arrangements for a foundation, or an educational institution, or a museum, or a regional parks and recreation department to take over the reins when Stata quits the stage. In the short term, a longtime co-worker will do so; but it’s a shame that arrangements haven’t been made to ensure the long-term continuation of this one-of-a-kind place, a place the Canadian rock band the Barenaked Ladies dubbed “the coolest theater in the world.” For, surely, as Stata himself says, “Somehow, the show must go on.”

Stata’s cinema may be off-the-beaten track, but it has received extensive media attention over the years from far and wide. The late Elwy Yost, of TVO’s

Courtesy of Keith Stata.

long-running “Saturday Night at the Movies,” made a professional pilgrimage here. The big Toronto daily papers have made repeat visits. And, 2024, director Matt Finlin released a feature-length documentary about Keith Stata and the Highlands Cinema: “The Movie Man” is an award-caliber treat of a film about a man who loves films and single-mindedly made his labor of love in showing them to others a reality. It’s an utterly absorbing up-close-and-personal look at the man, fueled by his vibrantly colorful personality, with a large dollop of sheer pleasure for viewers in observing a dream come true: “The world needs more people like him who actually do what they believe in.”

There’s something else close to Stata’s heart, and that’s his love of the natural world and a resulting drive to protect its helpless orphans. His property has a cat sanctuary that’s home to 58 felines. They’re housed in several separate cat domiciles, with enclosed passageways suspended above ground for daily exercise. It’s a registered charity that relies on the kindness of strangers to cover the considerable cost of food, litter, and vet bills. Caring for those wards strikes us as a daunting labor, but for Stata, it is a labor of love, just as his self-made cinema in the wilderness was, is, and remains. As he tells his cinematic biographer in Finlin’s documentary, “Time is limited. You have to make the most of it. The only significance we have is whatever we do here.”

Copyright © 2025 by John Arkelian.

John Arkelian is film critic and editor at Artsforum Magazine and director of the Cinechats Film Program.

The foregoing also appeared in the Summer 2025 edition of Grapevine Magazine.

Visit the Highlands Cinema at: https://www.highlandscinemas.com/

See the trailer for “The Movie Man” at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7FQgwvTJTc

*********************************

Father Goose: Remembering Bill Lishman

© By Bill Eull

Bill Lishman and feathered friends flying into the sunset — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

It was the eyes, I think, that caught you first. I don’t mean the first time you met Bill but anytime you crossed his path. You’d notice the shiny alertness and then you’d see the delight: he’s glad to see you. And that’s when you recognize the extra meaning in the look: he has a story to tell. He is tickled to tell it. He wants you to hear it. And then you are both underway.

I met Bill Lishman over a quarter of a century ago. The first time I saw him was a little earlier than that. On my way to work, driving along Island Road in Port Perry shortly after dawn, I saw him flying overhead in his Easy Riser, with maybe a dozen geese ‘vee-ing’ off on either side. I was in awe. Bill Lishman drew that same awe from millions of people in those days as he worked his way to a solution to

Bill Lishman — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

the questions: “I wonder if we could train birds to overcome their historical migratory patterns which took them through dangerous hunting areas?” And, “I wonder if we could teach them a better route?” What he discovered was that “We can…and we did”.

But he didn’t start out with that pair of questions. It all started with a boyish wish to fly. To be with the birds. Bill grew up on a farm in a family that had great reverence for the land and for Nature. He absorbed those values and made them his own. He teamed those values with an intense curiosity and powerful urge to action. He was always doing things. Sitting still was not an option. He had trouble in the classroom. He wanted to get his hands on things. It was later realized that he was dyslexic, but by then he had turned his focus and restless energies toward the wonders of nature and the environment.

His yearning to fly took him, at 13, to air cadets. He drilled with his unit, taking the classroom demands with a self-discipline he hadn’t discovered in regular school. He worked to get into the pilot’s seat. He did well until he took the physical. He was found to be colour-blind, an impediment to flying in the military or even in commercial aviation. He was devastated and frustrated. But he refused to give up on the dream of flight. He discovered gliding, a form of flying that required no licence. He took lessons. His instructor has since said that he was his worst student (he always did things his way) and his best (he used flying to accomplish important things).

Bill bought a fixed-wing glider, large enough to carry a man. He found suitable hillsides up which he tugged his glider. At the top, he would wait for an updraft, launch himself into it and hope. He crashed a lot. When, after a while, he got tired of the crashing and pulling, he figured out how to attach a small motor to his glider, which by that time, was a bi-wing Easy Riser. He was the first Canadian to accomplish this. The engine allowed him to launch without the need for hills and updrafts. But it didn’t save him from crashing. He ruined some aircraft (but not himself, perhaps miraculously). When he mastered the skills to get and keep his craft in the air, he had at last found a form of aviation from which nobody could bar him because he was colour-blind.

Father Goose (Canadian artist, inventor, and visionary Bill Lishman) with geese and ultralight — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

Now that he was in the air, he turned his attention back to the birds. He was deeply moved when it occurred to him that his ultralight aircraft could match bird speeds and that he could birds from the top and side, unlike the earthbound view that only saw them from below. Now he could see the muscles moving. The artist and sculptor in him became riveted by what he saw. He sketched, made movies, took photographs. He treasured this new perspective on birds, their flight, and their mechanics. He became a student again. He studied ‘imprinting,’ the newly hatched chick’s instinctual adopting as parent the first living thing it sees. He decided to work with geese. They were big enough, flew at the right speed, and were interesting socially. He became ‘Father Goose.’

Having put so much focus and exertion into becoming Father Goose, Bill had to find a way to make those accomplishments worthwhile. That was the way his brain and heart worked. Once it was clear that he could indeed get a flock of geese to learn and retain a new migratory route, he was open to suggestions from naturalists that perhaps these new skills could be employed to save the almost totally extinct Whooping Crane. The rest is history. The Whoopers are, very slowly but definitely, increasing now that they are flying through much safer migratory lanes, taught using Bill’s methods.

While he was heavily involved with the bird experiments, he put his flying skills to other uses, as well. From his ultralight, he captured spectacular photographs of his beloved Oak Ridges Moraine, a geological marvel that runs north of Lake Ontario. Bill worried about its vulnerability to rampaging development. He published a coffee-table book containing hundreds of views “from above.” Bill was clear: the moraine was in grave danger and it needed to be taken seriously. He wrote the book because he wanted to make the moraine into a ‘rock star.’ That would make it less vulnerable. He had the same worry about the destruction of prime farmland around Toronto to provide ever more housing for the growing metropolis. He flew banners in protest, supported environmentalists in their causes, and was highly successful at drawing the community’s attention to the issue.

Just as Bill had a need to fly, it seems he had a need to burrow. He designed an intriguing underground home, based on the principles of the igloo – domed, interconnected, and round. He demonstrated that such a building could be practical, comfortable, and economical to run. In his later years, worried about the housing plight of Inuit people, he designed a large igloo-like housing unit that would accommodate over 40 families. While Bill has passed on, this housing idea has not. It is circulating among the powers-that-be and may yet come into being. Bill’s detailed drawings and descriptions of the innovative construction techniques required are available for study.

Bill’s naturalist bent and his passion to fly are well-known. But Bill was an artist, too. He was a carver and sculptor. He never lost his childhood need to get his hands on things, to shape and make them into something new. He was prolific. His major works, large bronze statues, mostly of animals or people in motion, were highly collectible and reside in personal collections and on public grounds throughout the world. He built an enormous structure depicting people in motion for the Vancouver World’s Fair. He created the dragons for Canada’s Wonderland. He again drew attention to himself when he created, in his backyard, a full-sized, exact scale “lunar lander.” It was bought and installed for public view in Tokyo. Today, it graces the Oklahoma Aviation and Space Hall of Fame. Recently, a very significant work was installed at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa: made of polished stainless steel, his “Iceberg” is 13 metres tall.

For a dyslexic, colour-blind kid who didn’t do so well in school, Bill didn’t turn out so bad. He wrote a best seller called “Father Goose” that was translated into four languages and turned into a very popular movie (1996’s “Fly Away Home”). He was bestowed with two Honorary Doctorates – one by Niagara University in New York, the other by Ontario Tech University. He was awarded with Canada’s Meritorious Service Medal by the Governor General. The U.S. National Wildlife Federation presented him with their Conservation Award. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. In January 2020, their journal, Canadian Geographic, identified the nation’s 90 greatest explorers. Bill was one of them. He was also a Fellow of the Explorers Club, who gave him their highest honour, the Stefansson Medal. And, ‘Odyssey of the Mind’ presented him with their Creativity Award

Bill lived with enormous energy and passion for understanding nature and preserving it. He could see its wonder, and he found ways to capture it so we could appreciate it, too. He was the best raconteur I have known: his stories were engaging and funny and his jokes were usually at his own expense. He was an adventurer who had the grace to bring his adventures and discoveries back to us so we could be inspired and uplifted. Bill’s stories were fun, but the real gift was the warm inclusive sparkle you invariably saw in his eyes.

Bill Eull, Ph.D., C. Psych. is a retired clinical psychologist and a long-time friend of Bill Lishman.

Copyright © 2020 by Bill Eull.

Editor’s Note: William Lishman (1939-2017) lived and worked near Port Perry, Ontario. A sculpture commemorating him is planned for that town’s Palmer Park, on the shores of Lake Scugog. For more, visit: https://scugogarts.ca/bill-lishman-memorial-project/

*********************************

To Fly Without Wings: The Royal Horse Show

© By John Arkelian

“O, for a horse with wings!” (William Shakespeare, “Cymbelline”)

Horse wrangler extraordinaire Guy McLean (courtesy of The Royal).

Now in its 91st year, The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair and Horse Show is the premiere event of its kind in Canada, bringing country and city together in a celebration of all things agricultural and equine. 340,000 people are expected to attend this year’s ten day indoor fair near the downtown of the nation’s largest city. Visitors can wander through stables and impromptu barnyards to observe horses, cows, chickens, pigs, and rabbits (some of which more closely resemble science fiction’s ‘tribbles’ than the more conventional looking mammals most of us are used to), and award-winning gourds of enormous proportions. There are culinary samples from Ontario’s important ‘agri-food’ industry (culled, for example,

Four-time Canadian champion Yann Candele on Showgirl (courtesy of The Royal).

from the province’s cheeses and berries), an array of leather products on sale, sculptures made of butter, a display of 332 eggs gleaned from a single hen over the course of 52 weeks, and judging contests of livestock and canines. But the jewel in the Royal crown has to be its Horse Show. Beloved of horse-set insiders and lay-folk alike, it is guaranteed to please one and all.

On Saturday, November 2nd, the highlight of the show was a horse trainer from Down-Under. Australian Guy McLean is horseback kin to his fellow countryman Steve Irwin, the late wildlife expert who was better known to

Courtesy of The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair & Horse Show

his television fans as the “Crocodile Hunter.” (There’s a dash of Paul Hogan’s “Crocodile Dundee” in him, too.) McLean’s milieu is the equine rather than the reptilian, but he shares the same infectious enthusiasm, energy, and humor as his fellow Aussie. Mounted on one of his five horses, McLean does a slow-motion pantomime of galloping, then plays traffic cop for his quartet of riderless horses. They respond to his gentle urgings like well-behaved children; and the result is utterly charming, not to mention astonishing! One horse lies calmly prone while three others stand over it, straddling its recumbent body. McLean and his mount canter on the spot, then they hop across the ground (48 times!) in a prancing move McLean dubs “flying

Courtesy of The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair & Horse Show

changes.” And there are equine calisthenics and horseplay galore, with man and horse moving sideways, diagonally, backwards, forward, and every which way at all. McLean’s élan is irresistible, and his act is worth a visit to The Royal all on its own.

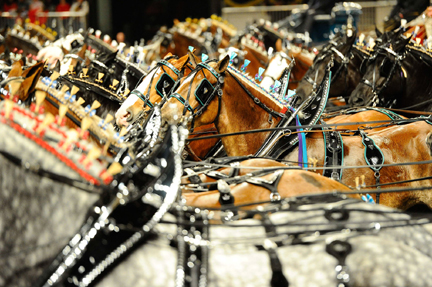

But, there’s more, so much more. Two-horse teams of imposing Clydesdales pull ornately gleaming wagons. Amber Marshall, star of CBC Television’s “Heartland” introduces a rodeo demonstration, with four young girls swirling lassos in a western variation on rhythmic gymnastics and two older girls racing by with trick-riding stunts, hanging from their saddles in true dare-devil fashion. Then bundles of energy and speed known as Jack Russell terriers tear across the ground in hot pursuit of a lure, though the pups among their number have minds of their own about the rules of the race. Then eleven contestants vie for ribbons in an event in which single hackney horses pull small carriages. (Things take a briefly disturbing turn, when the prize-winner crashes head-first into a barrier — happily without incurring any harm.) Next up are the 1900-pound percherons, pulling two-wheeled carts. The evening show starts off with “eventing” in which riders essay an obstacle course: One of them, Olympic silver medalist Jessica Phoenix, has a bad spill after her horse hits the bars on the last hurdle, but her inflatable vest (a kind of portable airbag) saves the day. The jumping competition to come is the night’s flagship event, with numerous competitors taking on the 15-gate course. One favorite with this observer is the black horse Bobby (ridden by Christian Sorenson), who’s fond of running with his tongue lolling out, and whose red ribbon adorned tail warns that he’s a kicker. Canadian star Ian Millar makes an impression atop Star Power; while the curious conjunction of nomenclature between Beth Underhill and her mount Viggo won’t be lost on aficionados of the cinematic version of “The Lord of the Rings” (Underhill is the traveling pseudonym for Frodo Baggins, and Viggo Mortensen is the actor playing his guide Strider). But the night belongs to Yann Candele atop Showgirl; together they claim the prize as four-time Canadian champion. In a rare quiet moment, a proverbial wag in the balcony, musing about changes to The Royal over the years, says that, “I miss the parade of moth-balled ball gowns.” And, as dressage is not on the on agenda on Saturday evening, we miss the wondrous sight of a horse dancing on tip toes. But, what we do see amazes, captivates, and enchants.

Copyright © November 2013 by John Arkelian.

The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair and Horse Show runs from November 1 – 10, 2013 at Exhibition Place in Toronto. Visit The Royal at: http://royalfair.org/