Reviews of Films on DVD

© By John Arkelian

“Anna Karenina” (U.K., 2012) (B+): “I’ve got nothing left except you. Remember that…. You’ve murdered my happiness.” Those prophetic words, spoken by one of literature’s great tragic heroines to the man who is about to

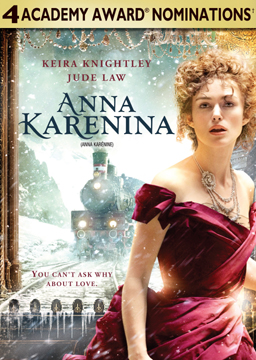

Keira Knightley in "Anna Karenina" (photo by Laurie Sparham, courtesy of Alliance Films)

become her lover, are uttered partially in jest; but they prove to be both true and prescient. For, in Leo Tolstoy’s sprawling, 864-page novel (originally published in installments in 1873-77), fierce, all-consuming passion truly does prove fatal to happiness. Or, perhaps it is as one of the novel’s translators observed, that one cannot build one’s happiness on another’s pain. In a boldly unconventional retelling of the novel that Time magazine listed among the ten best ever written, director Joe Wright (who also directed 2005’s big screen adaptation of “Pride & Prejudice”) offers a highly theatrical staging. Many scenes literally take place inside an old ornate theater, with groups of office workers moving in choreographed unison, one scene gradually bleeding into another, and a character leaving a formal party by climbing a ladder leading to the catwalks  overhead. This stylized and overtly theatrical approach is visually intriguing — rich with opulent costumes and sets — but it also keeps those scenes at one remove from the viewer on an emotional level, insofar as the artifice of the storytelling becomes a deliberate part of how the story unfolds. There is a great deal going on in Tolstoy’s story — with an ensemble of characters demonstrating the import of the book’s opening words, that, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” It’s a story about the elusive thing we call happiness; but it is also very much about great passion, social and personal hypocrisy, selfishness versus selflessness, emotional insecurity, jealousy, faith, fidelity, marriages both good and bad, social change, and the respective merits of rural and urban life. It may be that the character Levin, a man sincerely interested in “living rightly,” is a semi-autobiographical representation of Tolstoy himself. But, at the heart of the story is the ill-fated passion of a married woman — the film’s flawed eponymous heroine — for a dashing officer who is not her husband. She gives up everything for love,

overhead. This stylized and overtly theatrical approach is visually intriguing — rich with opulent costumes and sets — but it also keeps those scenes at one remove from the viewer on an emotional level, insofar as the artifice of the storytelling becomes a deliberate part of how the story unfolds. There is a great deal going on in Tolstoy’s story — with an ensemble of characters demonstrating the import of the book’s opening words, that, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” It’s a story about the elusive thing we call happiness; but it is also very much about great passion, social and personal hypocrisy, selfishness versus selflessness, emotional insecurity, jealousy, faith, fidelity, marriages both good and bad, social change, and the respective merits of rural and urban life. It may be that the character Levin, a man sincerely interested in “living rightly,” is a semi-autobiographical representation of Tolstoy himself. But, at the heart of the story is the ill-fated passion of a married woman — the film’s flawed eponymous heroine — for a dashing officer who is not her husband. She gives up everything for love,

Keira Knighley in "Anna Karenina" (photo by Laurie Sparham, courtesy of Alliance Films)

uttering in the throws of the unbridled passion she has never experienced with her good, but unpassionate husband, the words, “This is love! This!” Presentiments of Anna’s doom recur at intervals throughout the film, with the sight and sound of an approaching train. Anna’s society tolerates infidelity in men, but it shuns women who transgress — at least it does if they flaunt their affairs or treat them as more than a trifle. Anna is mercilessly ostracized by society, a society in “the laws are made by husbands and fathers,” which is to say, by men. A disdainful woman says, “I’d call upon her if she’d only broken the law. But she broke the rules.” Anna’s own brother, a shameless serial philanderer, deems it “impossible” to offer succor to his outcast sister. The film offers strong performances from its ensemble cast, among them: Keira Knightly (as the passionate Anna, who is stifled by the demands propriety makes upon her); Jude Law (as her stiff, duty-bound, but still sympathetic husband); Kelly Macdonald (as Anna’s sweet sister-in-law Dolly); Matthew Macfadyen, who was Darcy to Keira Knightley’s Elisabeth in “Pride & Prejudice” (here playing her brother Stiva); Alicia Vikander (as Kitty) and Domhnall Gleeson (as Lavin). Aaron Taylor-Johnson is something of an acquired taste as Count Vronsky, the man with whom Anna conceives an all-consuming passion. At first, he comes across as rather too young and too ‘pretty;’ but, as the story progresses, he develops more facets. But, above all else, the film is a visual delight — full of sumptuous beauty and fecund inventiveness. There are a myriad of examples: The back of the stage opens to an expansive winter landscape. When Anna and Vronsky first dance, the other couples freeze motionless in pose for a few seconds as the couple whom only haves eyes for each other pass; and when Vronsky lifts Anna off the ballroom floor, she shudders in reaction, a visceral signifier of their nascent passion. The dancers make strange sweeping motions with their hands that seem to be emblematic of some choreographed rite rather than actual ballroom dancing motions. At a later party, women flutter their fans in unison like stylized swan wings; while Anna’s own fan movements later echo both the pulse of her own beating heart and the approaching hoof-beats of racing horses. And, time and again, we catch glimpses (as does Anna) of the grinding wheels of a locomotive, as the implacable harbinger of inevitable doom. Karenin warns Anna of what is coming: “You would be lost, irretrievably lost;” to which Anna can only reply, “All I know is that I sent him away, and it’s as though I shot myself through the heart.” Her story is one of overpowering emotion, of passions too potent to be ignored, and of impossible choices that can have no happy ending. For sheer visual panache, elegant performances, and compelling storytelling, “Anna Karenina” is easily among the year’s best films. “Anna Karenina” was nominated for Academy Awards for Cinematography, Music, Costume Design, and Production Design. At BAFTA, it won Best Costume Design and was nominated as Best British Film of the Year and in four other categories. It was nominated as Best Original Score (by Dario Marianelli) at the Golden Globes; it was nominated for Outstanding Achievement by the American Society of Cinematographers; and it was nominated for Excellence in Production Design by the Art Directors Guild. DVD extras include a director’s commentary, eight deleted scenes, and several useful featurettes. One of the latter discloses the thinking behind the costume design, which unexpectedly mixes 1950’s couture with 1870’s silhouettes. In Anna’s case, the look they were after was ‘a distillation of chic, luxury, and elegance.’ For ages 16+: Mild sexual content.

“Crazy Stupid Love” (USA, 2011) (B): When you meet your soul-mate, it’s supposed to be for life, right? That’s what Cal (Steve Carell) believes, anyway. He met the love of his life, Emily (Julianne Moore), in his teens. She was his first and only love, and he never dreamt that that could change — right up until the day she abruptly announces (in the first few minutes of the film) that she wants a divorce. Cal is shattered. He retreats, in self-pity, to the local bar that happens to be the chief playing field of Jacob (Ryan Gosling), a smooth operator and expert pick-up artist who leaves with a different beautiful woman on his arm every night. Jacob may not be subtle (“I guarantee you this: You’re never going to regret going home with that guy from the bar that one time that was a total tom-cat in the sack.”), but he makes up for it in self-confidence — and in a near-perfect ‘batting average.’ The one catch that eludes him is Hannah (Emma Stone), a flame-haired young woman who’s about to write the bar exams. Cal and Jacob cross paths at the bar, and Jacob resolves to take Cal on as a reclamation project. Recovering Cal’s “lost manhood,” as Jacob puts it, involves an extreme make-over, Lothario-edition (first to go are the Super-Clips haircut and the wallet that, quite literally, closes with Velcro) — and the human re-engineering process that follows is quite funny! The remodeled Cal starts to try his prowess at the bar (with such lovelies as Marisa Tomei); but, outward changes aside, his heart still beats for only one woman. And his 13-year old son Robbie (Jonah Bobo) is truly a chip off the old block — a confirmed romantic even at his tender years, he lives for two things — reuniting his sundered parents and winning the affections of his 17-year old babysitter, Jessica (winningly played by former competitive figure skater Analeigh Tipton), a girl on the threshold of young womanhood who, in turn, secretly pines for Robbie’s father! A tangled romantic comedy of errors ensues; and, in a plot turn almost worthy of a Shakespearian comedy, the libertine learns that his life of casual relationships is no substitute for the real deal: “I looked at people who were in love, and I thought the way that they were behaving and the things they were doing and saying… appeared pathetic. And I spent all this time with you, and I was trying to make you more like me; and it turns out, I just want to be…” Be? Be like Cal, perhaps? But that’s not giving anything away in a story that twists and turns in unexpected directions and keeps viewers amused all along the way. Those of us who regard ourselves as shameless romantics may yearn for straight-up (i.e. dramatic) cinematic romance (it is almost invariably — and usually inanely — twinned with comedy in contemporary Hollywood movies); but, this is one romantic-comedy combo that offers equal helpings of laughs and touching moments. “Crazy Stupid Love” has an appealing cast, with John Carroll Lynch in an amusing turn as an irate father, and Kevin Bacon as ‘the other man,’ in addition to all the appealing players named above. Co-directed by Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, the film was nominated for a Golden Globe as Best Actor (Ryan Gosling). For ages 18+: Adult situations, some sexual subject matter, and brief coarse language.

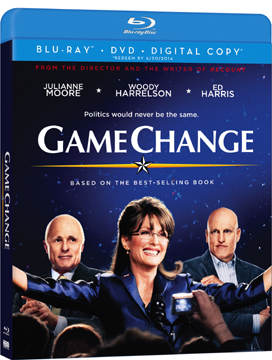

“Game Change” (USA, 2012) (B+/A-): “If he heals a sick baby, we’re really effed!” That’s the satirical appraisal of Barack Obama by his Republican

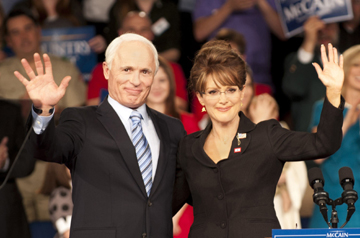

Ed Harris & Julianne Moore in "Game Change" (courtesy of HBO Films)

opponent, Senator John McCain, in the 2008 Presidential election campaign. McCain’s senior campaign strategist concurs: “He has 200,000 people screaming for him in Berlin. And what has he done? A man of no accomplishment has become the biggest celebrity in the world.” And how does one fight against star-power and celebrity? Why, with a game-changing counter move, of course. And the McCain team think they have found one in an instant celebrity of their own, the unknown neophyte Governor of Alaska, Sarah Palin, whom they hastily choose as McCain’s running mate and Vice-Presidential nominee: “We needed to do something bold to try to win the race.” And, at first, things look

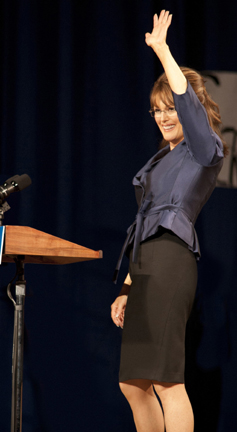

Julianne Moore in "Game Change" (courtesy of HBO Films)

promising. Palin’s hits her speech at the Republican convention out of the proverbial ballpark, wowing listeners with her charisma and straight-talking persona. At 44, Palin is an attractive mother of five; her eldest son is about to be deployed to Iraq; her infant son was born with Down’s Syndrome; she took on both big oil and her own party establishment; she has high approval ratings in her home state; and she’s a soccer mom who likes to unwind by hunting moose. She’s made to measure as a pin-up gal for a significant portion of the electoral demographic. As McCain’s staff observes, “She’s so outside the box, she helps you regain the maverick label… She’s everything we need.” But in a moment of prescience, McCain wonders if “she might be too outside the box?” As it turns out, Palin does have many admirable qualities — she’s well-meaning; she’s an exceptionally talented natural actress, and she has the sincerity of an everywoman who has not yet been jaded by the grueling game of politics. She is talented at giving speeches, and she connects with ordinary folk. But, on the down side, there are immense gaps in her grasp of many things, including the salient issues of the day. She seems willing to learn; indeed, she is eager at first to close the gaps in her knowledge. But it seems that her reach has exceeded her grasp. A sinking sense of her own inadequacy for the high office she is seeking is the catalyst that diverts her attention from pressing matters at hand to peripheral

Julianne Moore & Ed Harris in "Game Change" (courtesy of HBO Films)

distractions. She rankles at being a perceived puppet of campaign handlers, and one sympathizes with her indignation; but, she seems unwilling or unable to focus the concentration needed to master the issues at hand. Things quickly start to unravel when Palin does face-to-face interviews. Her self-assurance falters, and her bluff starts to show through. And yet, her magnetic appeal to crowds of supporters enables her to retreat into illusions of her own greatness and to blame her stumbles on others: “All you’ve done is get in my way. Oh. And I am raising millions of dollars for this campaign. Hundreds of thousands of people are coming to see me, not John McCain, God bless him. They are coming to see me; so, if I am singlehandedly carrying this campaign, I’m going to do what I want!” Based on the book by journalists Mark Halperin and John Heilemann, “Game Change” is one part character drama, one part political drama. Both parts are utterly absorbing, for here we have fascinating people struggling for the highest of political offices. Whether you like Palin’s political views or loathe them, you are certain to connect with her as a decent, if flawed, human being. As McCain says, in sympathy, after she seems to go rogue, “That poor girl. She wasn’t ready for this.” It’s a story about hubris, ambition hindered by limitations, good intentions compromised by expediency, and good judgement hampered by wishful thinking. (And there are early warning signs of the irrationally hateful attitudes about Barack Obama that still persist in some right-wing quarters, with a few people at McCain rallies shouting invectives like, “He’s a Muslim,” “He’s a socialist!,” “Send him back to Africa!”, and “Kill him!” about Obama — to the appalled consternation of McCain himself.) And the film’s exceptional performances are all award-caliber! Not only will you feel like you are eavesdropping in a room with the real McCain, Palin, et al., you will be astonished at how much you sympathize with their varied  struggles and doubts. Julianne Moore is simply remarkable as Sarah Palin: She channels the character with a verisimilitude that has to be seen to be believed. Every bit as good are Ed Harris as John McCain (a man who actually wants to take the high road), Woody Harrelson as his senior strategist Steve Schmidt (who comes to the gradual realization that he has made a dire mistake in suggesting Palin as a running mate), Sarah Paulson (as campaign adviser Nicole Wallace, who has the unenviable job of guiding Palin along the desired path), and Jamey Sheridan and Peter MacNicol as other members of the McCain team. “Game Change” is one of the most critically praised and heavily awarded films of the year. At the Golden Globes (in the made-for-television category), it won Best Film, Actor (Harris), and Actress (Moore), and it was also nominated as Best Actor (Harrelson) and Actress (Paulson). At the prime-time Emmy Awards, it won five awards, as Best Film, Actress (Moore), Director, Writing, and Casting, and it was nominated in seven other categories, as Best Actor (Harrelson), Supporting Actor (Harris), Supporting Actress (Paulson), Cinematography, Music, Single-Camera Editing, and Sound Mixing. The AFI (American Film Institute) Awards named it the Best Television Program of the Year. It won Best Actress at the Screen Actors Guild, where both male leads were nominated for Best Actor; and it was a nominee as Best Television Movie at the Writers Guild of America awards. Made for HBO, “Game Change” is much better than most of what is shown on the big screen. It is one of the best films of the year, and it is highly recommended! For ages 18+: Abundant coarse language.

struggles and doubts. Julianne Moore is simply remarkable as Sarah Palin: She channels the character with a verisimilitude that has to be seen to be believed. Every bit as good are Ed Harris as John McCain (a man who actually wants to take the high road), Woody Harrelson as his senior strategist Steve Schmidt (who comes to the gradual realization that he has made a dire mistake in suggesting Palin as a running mate), Sarah Paulson (as campaign adviser Nicole Wallace, who has the unenviable job of guiding Palin along the desired path), and Jamey Sheridan and Peter MacNicol as other members of the McCain team. “Game Change” is one of the most critically praised and heavily awarded films of the year. At the Golden Globes (in the made-for-television category), it won Best Film, Actor (Harris), and Actress (Moore), and it was also nominated as Best Actor (Harrelson) and Actress (Paulson). At the prime-time Emmy Awards, it won five awards, as Best Film, Actress (Moore), Director, Writing, and Casting, and it was nominated in seven other categories, as Best Actor (Harrelson), Supporting Actor (Harris), Supporting Actress (Paulson), Cinematography, Music, Single-Camera Editing, and Sound Mixing. The AFI (American Film Institute) Awards named it the Best Television Program of the Year. It won Best Actress at the Screen Actors Guild, where both male leads were nominated for Best Actor; and it was a nominee as Best Television Movie at the Writers Guild of America awards. Made for HBO, “Game Change” is much better than most of what is shown on the big screen. It is one of the best films of the year, and it is highly recommended! For ages 18+: Abundant coarse language.

“Searching for Sugar Man” (Sweden/U.K., 2012) (A-): “What he demonstrated very clearly is that you have a choice. He took all that torment, all that agony, all that confusion and pain, and he transformed it into something beautiful… Insofar as he does that, I think he’s representative of the human spirit, of what’s possible. That you have a choice.” That’s what a philosophical working man in Detroit says about his friend — the construction worker and day-laborer Sixto Rodriguez. For Rodriguez is also a towering musical talent, a singer/songwriter equal in stature to Bob Dylan, who remained entirely unknown in his native America, even as, unbeknownst to the artist himself, this “hippy with shades” became a rebel icon in the ultraconservative apartheid era society of far-off South Africa: “To many of us South Africans, he was the soundtrack to our lives.” In 1970, a pair of music producers went to see Rodriguez, this undiscovered phenom of whom they’d heard rumors, in a riverside Detroit bar that was filled with smoke so thick you could cut it with a knife. And there he was, sitting in a corner, with his back to the bar’s patrons, singing unforgettable songs that embodied the mean streets and the struggles of the working poor. “Detroit in the 70’s was a hard place. Well, it’s still a hard place. Lots of decay, lots of ruined houses. Real poverty exists in this city. And those streets were Rodriguez’s natural habitat… He was this wandering spirit… a drifter… We thought he was like the inner city poet… a wise man [and] a prophet.” The producers signed Rodriguez and two record albums (“Cold Feet” and “Coming from Reality”) followed. But they flopped — notwithstanding the sheer, unmistakeable brilliance of the lyrics, music, and vocals — and Rodriguez slipped back into obscurity. He slipped back into obscurity, that is, everywhere but in South Africa. There, this mysterious figure, about whom nothing was known save his music, became a living legend. In fact, his music was the inspiration for the white liberal middle class opposition to apartheid. Urban legends sprang up purporting that he had dramatically killed himself on stage; but, in 1998, two determined fans in South Africa became amateur sleuths, tracking their hero down in the place where he’d started — the rough streets of inner city Detroit. There Rodriguez was doing what he’d always done — hard manual labor, renovating houses and carrying old refrigerators down staircases on his back! His records had ‘gone gold’ ten times over in South Africa, but Rodriguez knew nothing of their runaway success there; nor did a penny of the royalties sent to his U.S. record label ever reach him. But that didn’t embitter this unpretentious man. Instead, he raised his three daughters with the conviction that a person’s dreams and self-worth should not be limited by their material poverty. When his adoring South African admirers learned that their musical luminary was alive and well, they brought him to Cape Town, where Rodriguez serenely took to the stage to perform six consecutive concerts to sold-out crowds of thousands of rapturously elated fans. The result is a wonderful real-life fairy tale, a story that has to be seen to be believed, with a protagonist who is modest, soft-spoken, shy, gentle, and incredibly talented. Directed by Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul, “Searching for Sugar Man” is one of the best films of 2012. The film is currently a leading contender for Best Feature-Length Documentary at the upcoming Academy Awards. It has attracted many awards and nominations elsewhere. It won the Audience Award and Special Jury Prize at Sundance, where it was also nominated for the Grand Jury Prize. It won the 2nd Place Audience Award at Tribeca; it won the Audience Awards at the Amsterdam and L.A. Film Festivals; and it won Best Documentary at film festivals in Moscow and Athens. It is a nominee for Best Film and Best Screenplay at Sweden’s Guldbagge Awards; and it is a nominee as Best Documentary at BAFTA in the U.K. “Searching for Sugar Man” is a must-see! For ages 18+: Very brief coarse language.

“Arbitrage” (USA, 2012) (B+): Hedge-fund magnate, oracle of high finance, and billionaire, Robert Miller (Richard Gere) is one of those uber-wealthy Wall Street financiers who regard themselves as “masters of the universe.” The story opens with him being admiringly interviewed for his accomplishments. He is on the verge of selling his company for hundreds of millions of dollars, he is a prominent philanthropist, and he has a bright, beautiful wife, Ellen (Susan Sarandon) and an accomplished daughter, Brooke (Brit Marling). The world is his oyster, as the saying goes. He embodies and projects a certain image — the image of success. But things are fraying beneath the surface: A sure-thing investment (involving copper mines in Russia) has gone terribly wrong. As a consequence, Miller has had to rob Peter to pay Paul, and he’s desperate to sell his company before anyone discovers the gaping hole in its books. Defending his unlawful and unethical actions to his principled daughter, Miller proclaims: “I am the oracle. I have done housing. I have arb’d credit swaps. I have done it all. And yes! I know! It’s outside the charter, but it is effing minting money! It is a license to print money! For everybody. For ever! It is God!” “Until?,” his daughter asks. “Until it’s not,” Miller replies. He is walking on the very precipice of imminent financial catastrophe; but, as if that weren’t bad enough, troubles with his mistress Julie (Laetitia Casta) and his involvement in a fatal motor vehicle accident have given Miller another urgent reason to stay one step ahead of the law (in the persistent person of a detective played by Tim Roth). Gere does award-caliber work in this directorial debut from writer/director Nicholas Jarecki: Here is a man who has dedicated his life to ego and to accumulation. He lives for the trade, he’s obsessed with the deal, and he measures everything according to its value in cold hard cash. Yet, the remarkable thing — about the movie and the man — is that he still possesses a heart and a hold on our sympathies. He is a flawed man, yes, but he is not a fundamentally bad one. The film takes its title from a term from the world of finance: ‘Arbitrage’ refers to the purchase of currencies, securities, or commodities in one market for immediate resale in another market where their price is higher. It’s all about profiting from speculation (and sometimes from inside information). Writer/director Jarecki likens his antihero to a shark, who must keep moving to survive. But, unlike too many real-life financial crooks, Miller does not set out to defraud anyone. Rather, he is simply too enamored of his own Midas touch, too given over to the compelling force of sheer ego and the intoxicating hubris of imposing his will on the world around him. The result has something of a Greek tragedy about it. This fine film combines subject matter (large-scale financial chicanery) that is torn from the headlines with strong character drama and suspense film conventions. There are also some subtle elements of social satire, as we discover just how many people and institutions on both sides of the law are willing to lie and cheat in order to get what they want. The combined Blu-ray/DVD release from VVS Films offers two featurettes and deleted scenes on the former disc. The director’s commentary can been accessed on both discs, and a fascinating commentary it is, too, canvassing everything from the choice of songs (like “My Foolish Heart”) to the German concept of “schadenfreude” (taking pleasure in another’s misfortunes) to Aristotle’s “Poetics” (penned nearly 2400 years ago). “Arbitrage” was named one of the year’s Top Ten Independent Films by the U.S. National Board of Review; and Richard Gere was deservedly nominated as Best Actor at the Golden Globes. For ages 18+: Coarse language.

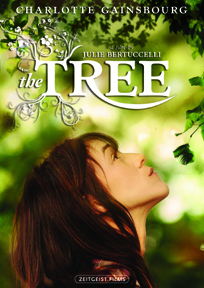

“The Tree” (Australia/France, 2010) (B/B+): When an eight year old girl’s father dies suddenly, she becomes innocently convinced that he is  whispering to her in the rustling leaves of the immense Moreton Bay fig tree that looms over her family’s home in Australia’s Outback. Shot on location in Queensland, the ruggedly beautiful setting infuses this gentle story about loss, inconsolable grief, longing, and the hope of renewal, taking on a personality of its own. Despite the hint of ‘magic-realism’ in its premise, what we see and hear is thoroughly rooted in the natural world: The creaking of this majestic tree’s limbs, the rustling of its leaves in the wind, and the flora and fauna that shelter under its boughs are viscerally real, thanks to the film’s quietly understated tone. Only 40-ish when he succumbs to a sudden heart attack, Peter O’Neill (Aden Young) leaves behind him a young wife (played by British-born, French-resident actress Charlotte Gainsbourg) and four children. Of the four, young Simone (winningly played by Morgana Davies) is the precocious tom-boy who first makes a connection between her late father and the tree under which he died. Her stubborn certainty about that

whispering to her in the rustling leaves of the immense Moreton Bay fig tree that looms over her family’s home in Australia’s Outback. Shot on location in Queensland, the ruggedly beautiful setting infuses this gentle story about loss, inconsolable grief, longing, and the hope of renewal, taking on a personality of its own. Despite the hint of ‘magic-realism’ in its premise, what we see and hear is thoroughly rooted in the natural world: The creaking of this majestic tree’s limbs, the rustling of its leaves in the wind, and the flora and fauna that shelter under its boughs are viscerally real, thanks to the film’s quietly understated tone. Only 40-ish when he succumbs to a sudden heart attack, Peter O’Neill (Aden Young) leaves behind him a young wife (played by British-born, French-resident actress Charlotte Gainsbourg) and four children. Of the four, young Simone (winningly played by Morgana Davies) is the precocious tom-boy who first makes a connection between her late father and the tree under which he died. Her stubborn certainty about that

Morgana Davies & Charlotte Gainsbourg in "The Tree" (courtesy of Mongrel Media in Canada and Zeitgeist Films in U.S.A.)

connection comes to influence how her siblings and mother view the tree, too. But, if it is a protective, watchful spirit, the tree also poses mounting challenges, in the form of tendrils that hold the house in a tight embrace and roots that threaten to tear the house loose from its foundations. Here is metaphor writ large, as a family goes through varied stages of grief. Gainsbourg’s Dawn is initially numbed by her loss, hardly ably to get out of bed in the morning, let alone care for her four children. Indeed, her character is not altogether likable, too often coming across as both mopey and dopey. In time, the possibility of her finding romantic companionship with a new man (played by Marton Csokas) brings Dawn into conflict with Simone and perhaps with the tree itself. But the tree roots blocking the house’s drains are highly suggestive of emotional blockages, about coming to terms with great loss and learning to carry on with the business of life despite that loss. French director Julie Bertucelli adapted “The Tree” from an earlier screenplay by Elizabeth J. Mars, who in turn adapted it from the novel “Our Father Who Art in the Tree” by Judy Pascoe. While the adult lead Gainsbourg fails to strike a sympathetic chord with this reviewer, that discordance may be a subjective one. Others may warm to her character; and even if they do not, the film offers ample compensations in the rest of the cast, in the strangely compelling setting, in the sheer originality of its premise, and in the film’s admirably understated tone. “The Tree” was nominated for seven Australian Film Institute awards, among them: Best Actress (for both its adult and child leads) and Director; while, in France, it earned Cesar nominations for Best Actress, Adapted Screenplay, and Music. “The Tree” is distributed on DVD in the United States by Zeitgeist Films and in Canada by Mongrel Media. The Canadian version has no DVD extras, but the American release has the film’s trailer, nine very worthwhile deleted scenes (tallying up to over 22 minutes), and a half-hour documentary about the making of the film. What neither version has, however, is a commentary with the director and cast, and such a commentary would be very welcome for such a thoughtful, artful film. Mild sexual content and very brief coarse language.

“Facing Windows” [“La Finestra di Fronte”] (Italy/U.K./Turkey/Portugal, 2003) (A-/A): A quarreling couple, Giovanna and Filippo, played by the identically-named Giovanna Mezzogiormo and Filippo Nigro, come across a distinguished-looking old man (Massimo Girotti) who is clearly lost and helpless. He seems to be without any memory of who or where he is. Despite Giovanna’s misgivings, they give the old man temporary refuge; but he is haunted by the ghosts of past tragedy, and his sudden, unsettling presence in the already unsteady lives of others may prove to be a catalyst for unexpected change. For Giovanna is unfulfilled, surreptitiously observing a handsome neighbor (Raoul Bova as Lorenzo) across the courtyard each night from the vantage-point of her own discontentment. A story about choices, memories, desire, and the relationships that change our lives, this is one of the best films of 2003. It is intelligent and beautifully acted. You watch these faces intently. There’s a redemptive theme, a poetic sensibility, and nice big subtitles (that are easy to read for a change). “Facing Windows” is gently moving, utterly involving, very authentic in its emotional heft, and highly recommended: “You still have a choice. You can change… Don’t be content to merely survive. You must demand to live in a better world, not just dream about it. I didn’t do that.” This heavily honored film won five awards at Italy’s David di Donatello Awards, namely Best Film, Actor (Girotti), Actress, Music, and a Scholars’ Jury Award; and it was nominated in seven other categories, including Best Director, Screenplay, Cinematography, and Supporting Actress. It also won Special Recognition for Excellence in Filmmaking from the U.S. National Board of Review. “Facing Windows” was directed and co-written by Ferzan Ozpetek, who moved to Rome from his native Turkey and worked in live theater before film. The film’s musical score (by Andrea Guerra) has a central theme that is as powerful, haunting, and poignant as the most vivid of dreams. (If only the film score were available on CD in these parts!) For ages 18+: Coarse language; brief partial nudity; brief sexual content.

“Paradise” (USA, 1991) (A-/A): Is paradise as much a state of mind as it is a place? This gem of a film (which should not be confused with the 1982 “Blue Lagoonish” fluff of the same name) seems to have been overlooked by audiences and critics alike. And that’s a real shame, for this sweet, gentle coming of age story has a quiet poignancy and memorable performances. It elicits real emotions from the viewer, and that’s a rare quality indeed. One summer, ten-year-old Willard Young (Elijah Wood) is taken by his pregnant mother (Eve Gordon) to spend a few weeks with her best friend in the countryside. Willard is resistant to the plan, suspecting there’s more to his father’s long absence than he’s been told: (A) “Wake up… We’re here.” (B) “Where?” (A) “Paradise.” (B) “This is it?” As it happens, their destination is a pretty idyllic looking place; but there is veiled discord and unhappiness in this bucolic paradise. Willard is a very bright and unusually perceptive child; but he is also introverted and friendless. That changes in his new setting: He is befriended by the slightly younger but much bolder and more extroverted young tomboy Billie Pike (Thora Birch) and he gradually bonds with the married couple to whom he has been entrusted. But Willard can see that something is wrong between Ben and Lily Reed (Don Johnson and Melanie Griffith). Before Willard knows who Ben is, Ben tells him that he doesn’t like the Reeds anymore. Later, he says that, “Lily used to be different, not the person you know now. She didn’t used to be afraid of anything… She was so full of life, she gave off a sort of heat.” But Ben and Lily have suffered an awful loss, and it has left them sundered, bereft, and tormented by needless guilt: “I can’t stand to be touched. I can’t stand to feel anything. All I can stand is just to be numb instead. And to be sorry every single minute.” So, when the minister at the Sunday church service exhorts his assembled parishioners to “give your hand in forgiveness and love,” Ben sits with his arms folded across his chest, as Lily looks straight ahead. As she confides to the precocious boy in her care: “Sometimes things happen to people, hard things, and they get broken inside. I want Ben to come back; but I don’t know if I can fix what’s broken inside of me.” For this is a story about pain and loss, but also about forgiveness and love. And it’s about facing down the things that frighten us: “Don’t run away from things just because they scare you Willard. If you do, you’ll always be afraid. It’s a bad way to live.” In her directorial debut, screenwriter Mary Agnes Donohue has adapted and remade the award-winning film “Le Grand Chemin” [“The Grand Highway”] (France, 1987), which, in turn, was written and directed by Jean-Loup Hubert from his novel. Set in South Carolina, “Paradise“ is a gentle, wistful coming of age story, about reconciliation and love renewed. It boasts strong ensemble characterization and memorable performances by Melanie Griffith and Don Johnson (both of them admirably understated) as well as Elijah Wood and Thora Birch (both of whom are eminently believable as precocious kids who find an end to their friendlessness in each other), Canada’s own Sheila McCarthy, as young Billie’s colorful mother Sally, and Louise Latham (who makes a strong impression in one scene as a solitary artist), and Eve Gordon (who likewise creates a tangible sense of her character as Willard’s mother in just a few scenes). Birch won Best Young Actress at the Young Artist Awards, and Wood was nominated there as Best Young Actor. The beautifully emotional orchestral score by David Newman harkens back to the glory days of movie music. Its bittersweet ode to childhood adds a powerful emotional wallop to the movie, full of nostalgia, a sense of wonder, and the never-ending interplay between sadness and joy. Newman has scored many movies, earning an Academy Award nomination in 1997 for “Anastasia.” But, thus far, he has done his best work in “Paradise” and in 2005’s “Serenity. “Sadly, “Paradise” appears to have fallen out of print on both DVD and VHS. That’s a shame, because it is a real treasure. For ages 14+: Very brief partial nudity.

“Thirteen Conversations About One Thing” (USA, 2001) (A): Here are four intersecting stories about cause and effect, meaning, luck versus providence, and second chances. The result is remarkably intelligent, thought-provoking, and philosophical: “Life only makes sense when you look at it backwards. Too bad we have to live it forwards.” The captivating characters are portrayed by a note-perfect cast: Matthew McConaughey, Alan Arkin, Clea DuVall, John Turturro, and Amy Irving. Director Jill Sprecher co-wrote the script with her sister Karen. The “one thing” of the title is happiness: (Q) “What is it that you want?” (A) “What everyone wants. To experience life. To wake up enthused. To be happy.” In exploring the riddle of happiness, we meet one character who seeks freedom from a life of predictability and dull routine, only to find that his demons follow him into his new life. Another character is cynical and bitter about the happiness of others: “Show me a happy man, and I’ll show you a disaster waiting to happen.” But happiness isn’t a riddle for nothing: Its enigmatic and elusive ways defy comfortable formulations, as each of the film’s characters discover. Among its awards recognition, this film was nominated at the Independent Spirit Awards for Best Supporting Actor (Arkin) and Screenplay. “Thirteen Conversations About One Thing” is easily one of the best films of 2001, and it is highly recommended! For ages 18+: Coarse language.

“Morlang” (The Netherlands, 2001) (B+/A-): Julius Morlang (Paul Freeman), a successful British artist living in Rotterdam, may be over 60, but he is as vital and virile as ever. His muse, Ellen, also happens to be his wife; and the couple seem to be passionate about each other — artistically, sexually, and romantically. But Morlang comes to suspect that his wife may be having an affair with Robert (Marcel Faber), a younger Dutch artist; and, that perceived rival is also attracting the attention of Morlang’s longtime agent and friend Wim Giel (Eric van der Donk), who suddenly starts to find Morlang’s work to be insufficiently avant garde. How all of this affects Morlang is the stuff of subtle ambiguity. For Morlang is not given to outward demonstrations of emotion. Indeed, Ellen angrily confronts him about the impassive face he presents to the world: “Please come out of your effing shell!… Maybe I just can’t stand it anymore. Maybe I can’t stand your passivity. The way you keep everyhing bottled up is pure effing arrogance… You’re not so effing calm, are you? You’re bloody seething [but you won’t admit it].” When Morland develops a relationship with a lively younger Irish woman, Ann (Susan Lynch), is he striking out against Ellen? Director and co-writer Tjebbo Penning has fashioned a sleek, stylish character puzzle that combines first-rate performances, intelligence, and truly artful direction. At one moment, for instance, Morlang follows his wife to spy on her. But, instead of showing us what he espies, we see the emotional result on Morlang himself of whatever it is he sees. At another moment, someone comes to a crucial fork in the moral road; hesitating for a moment, that character looks out a window to visualize one course of action before walking out the door to very deliberately take a very different course of action. A Dutch film, performed in English by a mostly British cast, “Morlang” is a fine psychological drama about passion, creativity, jealously, deceit, and something darker — something seething beneath an outwardly calm surface. Its settings are divided between Rotterdam and coast of Ireland near the imposing Cliffs of Moher. Its story eschews histrionics in favor of subtlety, and it goes in some very unexpected directions! Though the film was honored at a couple of film festivals, it somehow seems to have eluded the attention and praise it so richly deserves as a very grown-up, very elegant psychological drama. For ages 18+: Coarse language; brief nudity; and brief sexual content.

“Incendies” (Canada, 2010) (A-): When a Lebanese-Canadian woman, Nawal (played with quiet power and dignity by the Belgian actress Lubna Azabel), dies suddenly in middle age, she leaves a series of troubling requests to her two adult children. The twins — Jeanne (Melissa Desormeaux-Poulin) and Simon (Maxim Gaudette) — are to search for the brother they never knew they had and for the father they always believed was long dead. In the process, they are sent on a journey into their mother’s past, into a life filled with unsuspected fire and frenzy — the fire and frenzy of great love, great loss, great pain, great suffering, and great endurance. Why has their mother instructed that she be buried naked and “face down away from the world,” without any headstone to mark her presence? The twins are about to find out, as they assemble the scattered pieces of the puzzle that is their mother’s past. Adapting his screenplay from the play by Wadji Mouawad, Canadian writer/director Denis Villeneuve’s film flows lyrically back and forth in time: We see Nawal’s story unfold as a young woman caught up in man’s monstrous inhumanity to man, even as we retrace her footsteps years later through the eyes of her Canadian daughter. The fulcrum of the story is the savage sectarian war that raged inside Lebanon between 1975 and 1990. That brutal internecine conflict took tens of thousands of lives and reduced a once proudly civilized and European society to savagery. When Jeanne embarks on her journey to discover the unspoken history of her mother’s tragic life, her kindly mathematics mentor succinctly summarizes the nature of what she has taken on: “Now you are embarking on a new adventure. You will face insoluble problems that will lead to other, equally insoluble problems. Friends will insist that the object of your toil is futile. You’ll have no way of defending yourself, for the problems will be of mind-boggling intensity.” Only later do we realize that those words, as accurate as they are for Jeanne’s quest, are even more apt for the monumental struggle of her mother’s life. “Incendies” is a riveting, heart-wrenching story about the connections between a mother and her children. Quietly powerful, the film will just about break your heart at times. We get caught up in the intersecting stories of Nawal, Jeanne, Simon, and their trusted family friend Jean Lebel (Remy Girard). Hatred, violence, and anger have dealt them a horrific series of blows; but they go on, each in their own way, refusing to be broken by adversity or by outright malevolence. Their story is rich is irony. It deals with very painful things; but, at its heart, it’s all about “a promise to break the chain of anger,” a promise that is born of love. The result is a powerful, emotional film that will stay with you long after you’ve seen it. “Incendies” attracted many nominations and awards. It was nominated as Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards and at BAFTA. It was nominated as Best Foreign Film at France’s Césars and Italy’s David di Donatello awards. It won eight awards at Canada’s Genies, namely, Best Film, Actress (Azabel), Director, Adapted Screenplay, Cinematography, Editing, Sound, and Sound Editing; where it was also nominated for Art Direction and Make-up. It won ten awards at Quebec’s Jutra Awards, among them Best Film and Actress, while it was also nominated for a second Best Actress award (for Desormeaux-Poulin). The U.S. National Board of Review named it as one of the year’s Top Five Foreign Films; and it won Best Canadian Film at the Toronto International Film Festival. For ages 18+: Very brief coarse language; war-related violence; and disturbing themes.

“The Queen of Versailles” (USA, 2012) (B+): “Everyone wants to vacation like a Rockefeller. We show them how they can. Everyone wants to be rich… The next best thing is to feel rich. That’s the guiding philosophy that made David Siegel, the founder and CEO of the largest privately-owned time-share company in the world, a billionaire. He takes pride in asserting that, “I personally got George W. Bush elected.” His wife is a former model and beauty pageant queen — a statuesque blonde fond of fur coats and small dogs. The mother of eight (seven of them by birth), Jackie also happens to be 30 years younger than David (she’s 43, he’s 74): “It took me awhile to fall in love with him. It felt wonderful to be so adored. That’s what attracted me.” When their story opens, they live in a very big house; but they have something even bigger in the works — an enormous, 90,000 square foot Floridian palace loosely modeled on Versailles. But the largest house in America is incomplete when the wheels fly off the American economy in 2008. Work on their mega-house (listed at $75 million even its unfinished condition) stops, and David’s biggest, boldest time-share complex, in Las Vegas, is imperiled by the bankers he and Jackie see as vultures. On the home front, cutbacks are called for — and some are made: Their staff of domestic servants is cut from nineteen to four, the kids exchange private schools for public ones, some pets expire from neglect, and, all the while, the family’s pack of little dogs leave their droppings hither and yon. But the couple is accustomed to living large (very large indeed); and, while the shopping may be done at Walmart, Jackie gets there in a stretch limo. David frets about more than just Jackie’s shopping sprees: “Every light in the house is on,” becomes his plaintive refrain. Is Jackie the proverbial ‘trophy wife?’ One daughter thinks so. After all, David did threaten to ‘trade Jackie in’ for two 20-year olds when she turned 40. Both of them came from humble origins. In Jackie’s case, her home town in New York State offered limited opportunities for advancement: “I figured I could either be a secretary and work for an engineer, or I could be an engineer.” She had the ambition and ability to opt for the latter, and she got a degree in computer engineering. But she soon bored of that work, flying away to the big city to work as a model instead. Jackie had intelligence, but she calculated that she could advance more rapidly and more dramatically by relying on her beauty. But physical beauty can fade with age, and Jackie takes preemptive measures with cosmetic treatments that leave her face looking temporarily burned and ravaged. On looking at what Jackie has undergone to maintain her beauty, David recoils from her post-treatment (and still raw) face, callously remarking that, “I don’t want to kiss some old hag.” With colorful characters that would be the envy of most fictional stories, filmmaker Lauren Greenfield has fashioned an irresistible documentary film about a couple who embody the so-called American dream and take it to its ultimate extreme. What’s remarkable here is just how engaging they are, proverbial warts and all. They may be filthy rich, but they’ve got an instantly recognizable array of eminently human foibles, worries, and vanities. They are funny, compulsively watchable, and, oddly enough, even a little poignant at times. Someone called “The Queen of Versailles” a funny allegory for the American dream. More than that, it may be a microcosm for the state of North American society — living beyond our means, transfixed by empty materialism, placing value on the superficial, gaudy, or crass, instead of the truly valuable things in life. Too often, as a society, we in the West overlook character in favor of cosmetic glitz, we buy things rather than manufacturing them, we neglect real family values, we put accessorizing above improving minds, and we foolishly prefer quantity to quality. That’s the bigger context to this film, which won Best Director in the documentary category at the Sundance Film Festival; but, at its heart, it’s the utterly fascinating story of two specific individuals — a pair we like, whatever their flaws.

“The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” (USA, 2011) (B+/A-): Given the strength of the 2009 Swedish film of the same name, it was hard to imagine what an English-language remake could possibly add. But, as it turns out, this remake stands on its own as a laudable cinematic retelling of Stieg Larsson’s bestselling novel. When disgraced investigative journalism Mikael Blomkvist (Daniel Craig) is engaged by the aging corporate magnate Henrik Vanger (a star turn by Canada’s Christopher Plummer) to look into the disappearance of a beloved niece 40 years earlier, the wealthy recluse tells him, “Someone in this family murdered Harriet… You’ll be investigating thieves, misers, bullies… the most detestable collection of people that you will ever meet. My family.” Blomkvist takes on the work, welcoming the opportunity it offers to escape his own recent notoriety, and his efforts soon bring him face-to-face with an unlikely ally. Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara) is outwardly as hard as nails — a Goth-girl, punk-rocker, computer hacker, complete with facial piercings that telegraph her street-cred as a rebel and outsider. But she is also badly wounded psychologically from a lifetime of abuse and neglect. Somehow, this improbable pair click — as workmates, friends, and perhaps more. The relationship between this 40-something man and this 20-something young woman, truly the oddest of odd couples, is at the very heart of the story’s hold on viewers. They are worlds apart in age, socio-economic status, and emotional make-up, but, somehow, they fit together. And it doesn’t hurt that they inhabit a story that’s pregnant with brittle suspense, a gnawingly ominous sense of dread, and superlative character work from the great Stellan Skarsgard and supporting players like Joely Richardson, Steven Berkoff, Robin Wright, Geraldine James, Donald Sumpter, Yorick van Wageningen, and Goran Visnjic. And it is all punctuated with startling moments of sudden, sometimes brutal, violence. Directed by David Fincher and written by Steven Zaillian, “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” won an Oscar for Best Editing; it was also nominated for Academy Awards for Best Actress, Cinematography, Sound Editing, and Sound Mixing. It won a Saturn Award as Best Thriller; it won Excellence in Production Design from the Art Directors Guild; it was nominated at the Golden Globes for Best Actress and Musical Score; and Rooney Mara was recognized by the National Board of Review as Best Breakthrough Performer. For ages 18+. Warning: Brief coarse language; nudity; sexual content; violence, including sexual violence; and disturbing content.

“Take This Waltz” (Canada, 2011) (C+/B-): Sometimes each of us is our own worst enemy. That’s true of all of the characters in Canadian writer/director Sarah Polley’s story about happiness being marred by restlessness. Early in the film Margot (Michelle Williams) watches costumed re-enactors at the Fortress of Louisbourg as they conduct a “public humiliation” of an adulterer: “Are you sorry? Are you contrite?” ask the disapproving voices of society’s guardians. The moment is full of foreshadowing; for it is the very time and place in which Margot meets Daniel (Canadian actor Luke Kirby), igniting an attraction that will gradually threaten to undermine Margot’s marriage to Lou (Seth Rogen). Fate (or contrived writing) takes a hand as Margot and Daniel happen to be seatmates on the flight back from Nova Scotia. They share a cab, and it turns out that Daniel lives right across the street (literally) in Toronto. (Such screenwriting contrivances would suit a romantic comedy better than a serious drama.) Proximity only fuels the fire of growing restlessness on Margot’s part. She seems discontented at home, for reasons that are never entirely clear. What is clear is that the odd games she plays with her cookbook writer husband grate on the viewer: One moment they are burbling in infantile baby-talk; the next they are exchanging mock-violent verbal quips of a sort better suited to eight year olds. Margot’s enigmatic restlessness is at the heart of the story: Is it fueled by feelings of neglect or boredom with her amiable spouse? Is it prompted by feelings of passion and/or love for ‘the other man?’ Or, is it simply a self-destructive yen for the figurative ‘grass on the other side of the fence?’ Margot’s sister-in-law Geri (played by comedian Sarah Silverman) is not too foggy from drink to guess that Margot is being tempted to stray; and she warns Margot that “New things get old” — words that take on pinpoint accuracy as the story progresses. “Take This Waltz” is a slow-paced, quiet film full of introspective conversation. The trouble is that it is better acted than it is written. The screenplay treads very near the borderlands of artificiality, contrivance, and affectation, and, perforce, it crosses that border at times: (A) “I want.” (B) “You want?” (A) “I want to know what you do to me.” At times, you will swear that you can hear the screenwriter behind the actors. And things sometimes get a tad pretentious. Among other missteps: What’s up with the lingering, utterly gratuitous nudity of several women (of varying ages and shapes) in a gym shower? Maybe that scene is meant to whet our appetites for the wildly excessive journey of sexual discovery depicted late in the film. Who knew that marital fidelity could be undermined by a hankering for “threesomes?” That improbable excess comes out of nowhere and nearly derails the film. Other improbabilities include: a couple with limited means (he’s a rickshaw driver, for heaven’s sake) inhabiting an enormous downtown loft, and a public swimming pool that’s open (but entirely deserted) at night, all too conveniently waiting to serve as a trysting location for a couple of aquatically-minded paramours. The film seems to be about Margot’s choice between comfort and security (in the person of Lou) and seeming excitement (in the person of Daniel). All of us can long for what we don’t have. But does desire lead to fulfillment or to more emptiness? “Take This Waltz” is too laid-back for its own good. It lacks energy. And, despite its solid performances, its characters (and their relationships) always feel off-kilter. None of it of it engages emotionally or viscerally, until, perhaps, its final scene. That moment has a poignancy one wishes was more evident throughout. “Take This Waltz” attracted two Genie Award nominations (Actress and Make-up) and four Director’s Guild of Canada Award nominations (Director; Editing; Production Design; and Sound Editing). For ages 18+: Coarse language; very frank sexual language in one scene; nudity; and sexual content.

Note: For another critic’s take on “Take This Waltz,” see Milan Paurich’s comment at: https://artsforum.ca/letters

“House of Dark Shadows” (USA, 1970) (B+/A-): When producer Dan Curtis dreamt up the idea for a Gothic television drama, he envisaged a

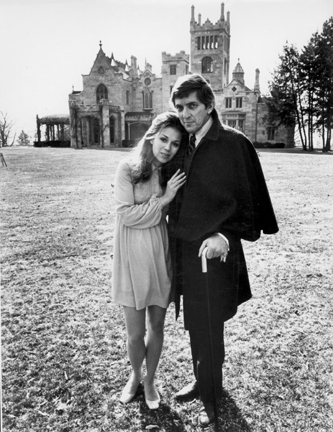

Kathryn Leigh Scott & Jonathan Frid in "House of Dark Shadows (courtesy of MGM).

dark-haired young heroine traveling by train along the rocky coast of Maine to take up a post as governess for the proud, wealthy family who lived in a sprawling mansion on the cliffs. It was a place that was full of secrets and suspense; and, the serial television drama, “Dark Shadows,” that Curtis’ dream inspired was the first (and well-nigh only) time that Gothic drama has ever formed the basis of a television series. Before long, it made a permanent detour into the realm of the supernatural, peopling its rich story-lines with all manner of werewolves, witches, and ghosts. But it was one particular supernatural character that made the 1966-71 series a major hit and sent its ratings soaring into the stratosphere. That character was Barnabas Collins, an eighteenth-century gentleman of means who is afflicted with vampirism as a consequence of a love triangle gone terribly wrong. (Whoever said that ‘hell hath no fury like a woman scorned’ must have had this story in mind.) Released from his chained coffin after 200 years of imprisonment, he introduced himself to the descendants of his family

Nancy Barrett in "House of Dark Shadows (courtesy of MGM).

as a long lost “cousin from England” and went on to win the intense abiding fascination of viewers. The secret to the character’s success is not difficult to discern: The noted Canadian Shakespearian actor Jonathan Frid, a man more accustomed to playing Richard 3rd and Caliban than a vampire, invested the character with palpable inner conflict, sadness, and self-loathing. Here, for the first time ever, was the vampire as tragic hero, a man with a terrible problem that puts his irrational, destructive side into implacable conflict with his sense of moral order. Reluctant, ambivalent, and romantic vampires are thick on the ground in fiction these days; but here was the first overtly sympathetic portrayal of a vampire! Jonathan Frid’s portrayal of Barnabas Collins as a tragic, romantic figure made him an enduring icon of American popular culture, as instantly

Jonathan Frid in "House of Dark Shadows (courtesy of MGM).

recognizable in the United States as fellow Canadian William Shatner’s inimitable portrayal of Captain James T. Kirk. The immense success of the television series prompted Curtis to make two motion pictures based on “Dark Shadows” for MGM. He made the first one, “House of Dark Shadows,” while the daily television series was still in full production, dividing the cast so some of them could concentrate on the motion picture while others carried the main brunt of responsibility for the television series. The first movie retells the story of the vampire’s arrival in the Collinwood of the 20th century. But because it tells a self-contained story, it leaves its key player in more villainous shades than those he gradually acquired on the television version. And, Curtis, who took on directorial responsibilities here, emphasizes violence and action far more than the television series did. Indeed, his star, Frid, never liked the film version’s indulgence in bloodshed and violence (both of which are very modest by today’s standards), holding that they did a disservice to the focus on intricate storytelling and character development that were hallmarks of the television version. But, “House of Dark Shadows” is a stylish, suspenseful drama that successfully blends elements of supernatural suspense, Gothic romance, and tragedy in engaging ways. It may add more ‘horror’ and violence to the mix

Nancy Barrett in "House of Dark Shadows (courtesy of MGM).

than the television version did, but it retains the High Romanticism that is at the heart of “Dark Shadows.” Its Barnabas Collins may be more villainous than the flawed hero his television self evolved into, but he retains the same preoccupations with lost love, sundered family, and shattered adherence to his own sense of right and wrong. The film benefits enormously from on-location shooting — much of it at the fabulous Gothic Revival-style mansion Lyndhurst, which towers above the high banks of the Hudson River in Tarrytown, New York, surrounded by its own forested estate. For a modest outlay of money, Curtis & Co. got access to a place that’s redolent with character, rich in elegance, and fully-stocked with its own antique furnishings. Curtis’s distinctive use of low camera angles is on display here; as is the work of his professionally inseparable musical composer, the Julliard-trained Robert Cobert, whose evocative themes — dramatic, melancholy, threatening, and delicate — always were the heart and soul of the “Dark Shadows” mythos. The cast, including the 1930’s and 40’s big screen siren, Joan Bennett and Academy Award nominee Grayson Hall (for “Night of the Iguana”), are entirely drawn from the television series, and they shine here — freed at last from the television series’ unfortunate use of “live-to-tape” recording, which precluded do-overs and sometimes yielded awkward results. Although “House of Dark Shadows” (and its less memorable 1971 sequel “Night of Dark Shadows”) were both released promptly on VHS and in the old laser-disc format), Warner Brothers (which acquired some of the MGM catalog of titles by way of Turner Entertainment) has waited an absurdly long time to release them (on October 30, 2012) on DVD and Blu-Ray. The veritable tsunami of DVD releases over the past dozen years somehow never included these two films. Why? Now that they’ve finally been released, it’s a crying shame that Warner opted for no-frill, bargain-basement releases. Despite a wealth of potential supplementary material, including lost footage from the second film (recovered by an avid fan) that would have restored it to its originally intended form, Warner offers no extras at all — no commentaries, no deleted scenes, no features on the cast, or on the late Dan Curtis, or on Cobert’s brilliant music, or on the franchise’s nearly half-century long existence and its avidly loyal fan following. Warner did not even use the original one-sheet art, logotype, or other promotional graphics from the films. Instead, it opted for drab, generic cover art which does no justice to the films. And in lieu of extras, all we get is each film’s trailer. Unsuspecting viewers of these DVDs would never imagine that “Dark Shadows” leapt from television to movies, then returned to television in 1991 with a new cast (Ben Cross, Jean Simmons, et al.) in a very sophisticated prime-time remake from Dan Curtis, and then tried for television a third time (in 2004) with still another cast, before crashing on the breakers of inane self-mockery, courtesy of Tim Burton and Johnny Depp’s dreadful 2012 parody on the big screen. “House of Dark Shadows” is not be missed by devotees of Gothic romance and romantic vampires. Everyone else will find good entertainment value here, too.

“The Devil’s Backbone” [“El Espinazo del Diablo”] (Spain/Mexico, 2001) (B+): “What is a ghost? A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain perhaps? Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph. Like an insect trapped in amber.” A ghost represents unfinished things, and that’s what this stylishly well-crafted film is all about. The setting is an old orphanage that sits like an isolated fortress in the midst of an arid plain. It’s 1939, and the Spanish Civil War is going badly for the Republican side. Their orphaned sons are cared for in the under-funded, under-staffed once-grand old hacienda in the desert. There is a faded elegance to the place, with its great hall of a dormitory and the tarps that cover unidentified contents in many of its rooms. Faded elegance is the term for the woman who runs the place, too. Bereft of her husband and her right leg (a prosthetic replacement gives her mobility), Carmen (Marisa Paredis) is refined and proper and still beautiful, despite the toll that time, stress, and disappointment have exacted. Her colleague, the gentlemanly Doctor Casares (very nicely played, with gentle humanity and a hint of quiet sadness, by Federico Luppi) loves Carmen; but he cannot give her the passion she craves. There is lovely poignancy to their inchoate love affair, a love that has spanned decades. There is a mysterious deep cistern of water in the basement beneath the kitchens; and there is a large unexploded bomb lodged in the earth of the central courtyard, a visceral, humming reminder of the war that rages just over the horizon. Into this strange place, a place that is seemingly set apart from the rest of the world, comes young Carlos (Fernando Tielve). Mere moments after his arrival, he encounters (and stands up to) the school’s bully Jaime (Inigo Garces) and he sees what he takes to be a ghost of a young boy. But writer/director Guillermo del Toro — the man behind 2006’s great “Pan’s Labyrinth” — is far too talented and original a filmmaker to settle for a conventional ghost story. This stylish, richly atmospheric film is really more of a character drama than a supernatural one; and the real monster of the piece is a living human being, a “lost one” whose own bitterness and anger at being “a prince without a kingdom… the one who was really alone,” find expression in coldness of heart and an inability to express any feeling save aggression. The result is as much about human conflict — arising from greed, fear, resentment, anger, and disappointment — as it is about the supernatural. The filmmakers challenge conventions in another way, too, by drenching their Gothic story in sunlight. Here, scary things move in broad daylight. Man’s inhumanity to man is a key part of the story, with echoes of the ruthless war that surrounds the school finding expression within its walls. But there is also something of hope, friendship, courage, and rough justice here, as young boys are obliged to cope with things for which their tender years have not prepared them. Watch for the director’s use of an incessantly moving camera and his fondness for doubling and duality in the way the story unfolds. The cast is very good, with Spain’s then teen heartthrob Eduardo Noriega cast decidedly against type, and Irene Visedo making an impression as the kind young woman, Conchita, who comes to see him as the psychopath he is. The film was nominated for Costume Design and Special Effects at Spain’s Goya Awards; and Stateside, it was nominated for a Saturn Award as Best Horror Film. For ages 18+: Some coarse language; brief sexual content; brief violence.

“Hugo” (USA, 2011) (B+/A-): A lonely young boy lives in the secret passages and catwalks of the Paris train station, tending to the station’s clocks. Bereft of his family, Hugo (Asa Butterfield) leads a sad and solitary life, unseen by others and always on guard against discovery by the martinet-like station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) who is relentlessly determined to apprehend and evict beggars and orphans from his zealously guarded turf. Hugo is fascinated by gears, coils, and levers — by what director Martin Scorsese calls “the machinery of creativity.” And he has inherited both his watchmaker father’s talent for fixing things and a broken automaton, that is, a robotic figure in the scaled-down form of a man. Hugo is obsessed with completing his father’s dream of making the automaton work again. But that mission brings him into contact and conflict with a bitter old toymaker played by Ben Kingsley. Can Hugo fix the living as successfully as he can fix inanimate objects? Can he find his own place in the world in the process? “Machines never come with any extra parts, you know. They always come with the exact amount they need. So I figured if the entire world was one big machine, I couldn’t be an extra part; I had to be here for some reason. And that means you have to be here for some reason, too.” Finding our purpose, what we are meant to do in this world, looms large in this story: “Maybe that’s why broken machines make me so sad. They can’t do what they’re meant to do. Maybe it’s the same with people. If you lose your purpose, it’s like you’re broken.” But, “Hugo” is also a celebration of the early, pioneering days of filmmaking, a time when we were less jaded and the powerful medium of film more often moved and astonished us, a time when it could more readily ‘show us our dreams in the middle of the day.’ Based on the book “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” by Brian Selznick, “Hugo” is a visually delightful recreation of Paris between the wars, conjuring a microcosm of the world inside the walls of a sprawling train station. Imaginative and poignant by turns, it is a story that embodies the words of one of its leading characters: “And now my friends… Come and dream with me.” Butterfield, Kingsley, and Cohen are supported by Chloe Grace Moretz (2010’s “Let Me In”), Ray Winstone, Emily Mortimer, Helen McCrory, Jude Law, Michael Stuhlberg, Frances de la Tour, Richard Griffiths, and the great Christopher Lee. The result is a modern variation on a Dickensian novel about an orphan’s search for home. The film earned a great multitude of nominations and awards. For example, it won five Academy Awards — as Best Art Direction, Cinematography, Sound Editing, Sound Mixing, and Visual Effects — and it was nominated in six additional categories — as Best Film, Director, Adapted Screenplay, Music (by Canadian composer Howard Shore), Editing, and Costume Design. It earned nine nominations at BAFTA, winning in two of those categories (as Best Sound and Production Design); and it won Best Director at the Golden Globes, where it was also nominated as Best Film and Music.

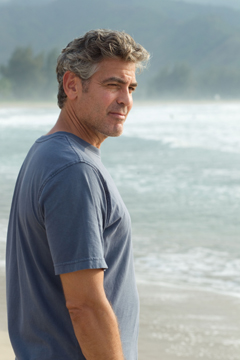

“The Ides of March” (USA, 2011) (A-): Is there room in politics for idealism, let alone integrity? Or is it a milieu inhabited only by jaded cynics, bald-faced liars, hypocrites, shameless manipulators, and self-serving egotists? Will politicians let us down every time? They are flawed human

Ryan Gosling & George Clooney (in poster) in "The Ides of March" (courtesy of Alliance Films).

beings like the rest of us, of course; but can they rise above their flaws to be genuine examples for the rest of us to follow? In this strongly acted piece of political suspense, Canada’s Ryan Gosling plays a media expert employed by a politician who seems to be the real deal. George Clooney, who also directed and co-wrote this film, is a Democratic Governor seeking his party’s Presidential nomination. He has ideas, he has charisma, and he seems to be a real hope for substantive change. In the eyes of Gosling’s character, “He’s the only one that’s actually going to make a difference in peoples’ lives, even the people that hate him… I don’t give an eff if he can win. He has to win!” Gosling is a hard-boiled realist, but he has to believe in his candidate. Will corruption rear its ugly head, and if it does, will it leave anyone unscathed? Clooney has assembled a strong ensemble cast, with himself as the candidate, Gosling as his communications chief, Philip Seymour Hoffman as his campaign manager, Paul Giamatti as his opponent’s campaign chief, Evan Rachel Wood as an intern with whom Gosling gets involved, Marisa Tomei as a journalist who can be a “friend” one day, a foe the next, and Jeffrey Wright as a Senator whose delegates give him a lot of bargaining power. Jennifer Ehle and Gregory Itzin do very good work in small roles as the Governor’s wife and a grieving father, respectively. “The Ides of March” earned critical praise and numerous nominations and awards. It was nominated at the Academy Awards as Best Adapted Screenplay (Beau Willimon co-wrote the screenplay, adapting it from his play “Farragut North”); and it was nominated as Best Film, Director, Actor (Gosling), and Screenplay at the Golden Globes. The film is part political thriller, part character drama, and both components are working at a very high level. Its characters engage us, and its story raises a host of fascinating questions about loyalty, integrity, and just how far any of us is willing to go to get what we want: “This is the big leagues. It’s mean. When you make a mistake, you lose the right to play.” For ages 18+: Frequent coarse language.

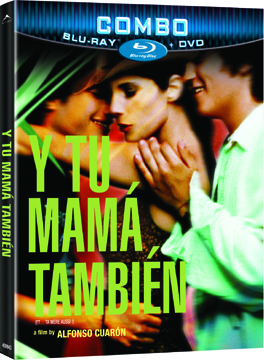

“Y tu mama tambien” [“And Your Mother Too”] (Mexico, 2001) (A-): Two 17-year-old boys lead a hedonistic existence that’s given over to girls and sex and booze and dope. One of them (Tenoch, played by Diego  Luna) is very well off; the other (Julio, played by Gael Garcia Bernal) is from the lower middle class; but they are inseparable best friends. And, did I mention that they are very preoccupied with sex, not unlike 17-year-old boys everywhere. When their girlfriends go off to Italy for the summer, the boys lose no time in seeking out alternative female company. That’s when they meet Luisa (the lovely Maribel Verdu of “Pan’s Labyrinth”). She’s newly arrived from Spain, as the wife of Tenoch’s obnoxious older cousin. Luisa is older (28), self-assured, and drop-dead gorgeous. She is also not at all inclined to accept the verdict of a quiz in a woman’s magazine that she is “a woman who is afraid to accept her freedom.” With hormones (and wishful thinking) in overdrive, the boys impulsively ask Luisa to accompany them on a out-of-town trip to a fabled beach of their own imagining on the Oaxacan coast. It’s a two or three day drive away; but don’t ask the boys to be too specific: “Julio and Tenoch had clearly no idea where they were… nor how to get to a place that did not exist,” observes the narrator. But that doesn’t stop the trio from embarking on a road-trip that becomes a journey of self-discovery for each of them, marked along the way by outposts of desire, jealousy, sorrow, loss, and acceptance. There’s tension and conflict in store for them, but also healing — not to mention some very frank depictions of sexuality. At times, we wonder what this all-grown-up woman could possibly see in a pair of teens who are pretty immature, not to mention crude. But Luisa bears troubling burdens of her own and seeks the freedom of the open road and beckoning coast. The result is a coming of age story told through a road-trip and an unconventional psycho-sexual tangle of competing needs. Writer and director Alfonso Cuaron (2006’s “Children of Men”) allows his camera to pan across the photo-laden walls of his characters’ homes, quietly giving us glimpses into their lives and pasts. In one scene, the camera lingers in Luisa’s apartment after she has exited it; and we watch her get into the boys’ car from her open window a few floors above, as though we are a part of Luisa that she has left behind. There’s lots of local color on this journey: In one scene a very old man shuffles into a room to collect payment from the travelers for some drinks while an equally old woman cuts a rug in the next room. And dryly ironic interjections by an unseen narrator put things in a more expansive context: Right after we learn that Luisa lost her first love in a traffic accident in Europe, the narrator notes, in a few matter-of-fact words, that a fatal automobile accident occurred some years past on the very stretch of road the trio are traversing — and, as we hear those words, we see a roadside shrine of two crosses beyond the window as the car passes by. So, tragedy in one place is mirrored by tragedy in another. There are hints of social commentary peeking in at the story’s margins: Our more or less privileged travelers pay no heed to the sight we see of soldiers leaping out of a vehicle to interrogate some peasants traveling a pied; and later, the narrator tells us the fate of a herd of escaped pigs and that of a contented fisherman who is displaced by condos and relegated to janitorial work in the towers erected for the wealthy. And humor is never far from the surface. When Luisa asks a provocatively pointed sexual question, the car itself overheats (along with the boys) in seeming reaction, in its case by emitting an ejaculatory burst of steam . Coarse, crude, blatantly sexual, raunchy at times, “Y tu mama tambien” has lots of dry, ironic humor but also moments of poignancy and wisdom. And it is very, very authentic from beginning to end. The film earned numerous awards and nominations, including a Best Original Screenplay nomination at the Academy Awards, a Best Foreign Language Film nomination at the Golden Globes, the Best Foreign Language Film and Screenplay nominations at BAFTA, and a Golden Lion nomination at the Venice Film Festival; it won Best Foreign Film at the Independent Spirit Awards. No DVD extras. This film is part of a three-film “Festival Collection” boxed set from Alliance Films, along with two other films from Latin America — “City of God” and “The Motorcyle Diaries.” For ages 18+. Warning: Very strong sexual content and nudity; as well as frequent coarse language (in Spanish).