Paul’s Stories

© By Fran Kolesnikowicz

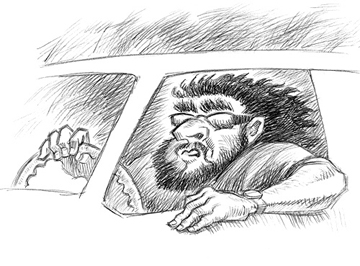

Sometimes Paul was just plain difficult. Other times my father-in-law was kind and easy to like. Throughout the years there would be times when he would bask in the joy of being with his family. Photos taken of him would show his happiness. However, sometimes when we visited him, he was full of rage — and storytelling. His stories were of his experiences during the war — horrific stories. History tells of how Belarus declared independence while under German occupation in 1918. Battles between the Germans and the Russians ensued with the Germans taking control until 1944. The German plan called for the extermination, expulsion, or enslavement of most or all Belarusians. When Walter and I were younger and first married, we sat and listened, but not really. We couldn’t relate to what he was talking about. We simply let him go on until he was finished.

Paul came to Canada after the war alone without his wife and two children. The Red Cross assisted him in relocating from his devastated home country, his family lost somewhere along the way. His mother and father, his six brothers and four sisters all gone. He was a survivor — maybe the only one, was far as he knew. He had been taken away by the Russians at first. The Russians sent him to bricklaying school. Soon afterward he found himself laying bricks for a factory. “We were kept in a locked boxcar for the night. We had little to eat. Sometimes it was just a rotten potato,” the story began once again. “We slept on the floor. For a bathroom, there was a hole cut out of the metal floor of the boxcar. No one cared if we were wet or cold. Some people died from lack of hygiene.”

And then the Nazis came to the farm where his family had previously led a prosperous life. It was night when they came, and they took Paul away still dressed in his nightclothes. His mother tried to give Paul some clothing but he was kicked and taken away without them. This time, he became a slave labourer for the Nazis. Treatment under the Nazis was no better than under the Russians. He was young and strong — the best candidate for the kind of forced labour they needed to ensure German victory in the war. “We were taken to an area in the woods where the railway tracks had been blown out by the previous day’s bombing. We tumbled out of the boxcar and gathered whatever tools we were given. We were marched to the devastated area,” his voice trembled recalling the memory. “They ordered us to replace the railway ties and put the rails back together.” As the morning went by, the men laboured, their stomachs growling with hunger from their inadequate food allotment, their throats parched from lack of water. Nazi guards watched mercilessly. Should anyone fall or fail to meet their idea of satisfactory work performance, they would quickly feel the butt of a weapon against their backs or the kick of the boot in their stomachs. Sometimes they were simply shot and left to die.

“As we worked, a British aircraft returned to prevent us from putting the railway back into working condition. The pilot fired his machine gun at us. We were strafed as if we were the enemy,” Paul continued, not really believing this could happen. “The Nazi guards shouted ‘Keep working or we will shoot you!’” as the guards took cover. There was little regard for the lives of their labourers. The plane came closer and chaos ensued, bullets flying everywhere. “I made a dash for the right side of the tracks. Some of the others went to the left side and ran deep into the woods. I ran as if my life depended upon it. In fact, it did. Others were coming too. And then, by some chance, we came upon a small village. The villagers took pity on us and gave us shelter and food for the night. I looked out of the window; somewhere, I could smell bread being baked. What a delicious smell! Life seemed normal. We were safe for the moment… But our time in the village was short. In the morning, the Nazis came and gathered us back up. We were taken back to the spot we had escaped from the previous day.” Paul hesitantly continued, “The men who had tried to escape to the left had been massacred.” He stared off into the distance.

“Another time, I was in the hospital,” he whispered, determined to tell us yet another story. We had no idea why he was in the hospital. We should have asked, but we didn’t. It seemed unbelievable that he could have received any kind of care while under German captivity. “Night was falling, and I drifted off to sleep. Suddenly, I woke up! Something told me to run. I did. I escaped,” he gasped. “Later, I heard that the Nazis came into the hospital and shot all the patients who had been hospitalized there. You wonder why I believe in God,” he stared at us, “That is why. Something, and I think it was God, told me to leave and I did. And I lived.”

Sometimes memories got jumbled up and connections were made that were not really there. We couldn’t figure out what kind of hospital he was in or why he was there. It might have been when he was in a deported persons’ camp for an appendectomy after the war. The story about the Nazis may have been just a story that the patients told each other. But in Paul’s mind it was real.

Eventually Paul’s wife and two children joined him in Val d’Or, Quebec. More children were born, and Paul and his family moved to Oshawa, Ontario, where he became an inspector at General Motors. Eventually, the children grew up and Paul became a grandfather and even a great-grandfather. His wife, Donna, died in 2001, but he went on for another twenty years. From the outside looking in, he had a fruitful life. However, those memories from his teens and early twenties kept coming back — his anger often lashing out at those to whom he should have been kindest. His anger was misplaced; but, in its wake feelings were hurt and relationships destroyed. The stories could come out at any time. He told them over and over. We had become immune to the horror of his past experiences.

Life went on until one day he was moved to a beautiful facility for people in need of 24-hour care. He had suffered a stroke and was quickly hospitalized. After undergoing physiotherapy and numerous brain scans and tests, the doctors determined this was the best he was ever going to be. Paul hated the place. He ignored the plethora of activities for the residents. He sat in his padded leather recliner and watched TV or dozed. Walter visited him. By then, we were finally ready to listen to his stories, but the stories had become disconnected and vague. Dementia had set in.

Sometimes the conversation during a visit was pleasant. “Sorry I can’t visit you in your new house,” he told Walter. Other times it was evident he had spent time reflecting on his life. “You work all your life and this is what it comes down to. It is just like when I was a prisoner in the war.” He was still angry. Another time, “I know I am going to die.” During one visit, Paul talked to Walter about his childhood days. “I couldn’t go to visit my grandfather’s grave at the cemetery. My parents wouldn’t let me go.” Excited that he might at last know something about his great-grandparents, Walter asked him, “What was your grandfather’s name?” “Grandpa.” Paul gave a sensible response for one remembering through childhood eyes. At least, Walter knew that his great-grandfather was buried somewhere in Belarus. Now and then, Paul would strike out in anger, “You don’t know what it was like! Stop asking me about them. Go away!” “Do you really want that? Because if you do, I will go away and I will not come back to visit you,” Walter retaliated. He had seen his father’s rage and anger before. His father sighed. No, he did not want that.

Paul died in May 2022 in great pain. Walter had made many visits to see him in the hospital. Later during the visits, Walter simply counted the time between Paul’s breaths. The hospital facilities were so crowded that Paul didn’t even have a room; instead, his hospital bed was in the hallway. In desperation one day he got some of his thoughts out, “Tell Walter to call the police. I need to get out of here!” We wondered if he was thinking about his escape from the hospital in Germany during the war. Finally, in the last few days of his life, he was given a small room to restore dignity to a life that had seen so much. It didn’t seem fair that someone who had suffered so much during the war should have to suffer yet again at the hands of another enemy. This time the enemy was cancer.

Fran Kolesnikowicz lives in Hampton, Ontario. After retiring in 2001 from education, she and her husband, Walter, enjoyed 17 years of international work and travel before returning to Canada in 2017. Engrossed with exploring her Polish ancestry and her family’s roots, she is at work on a memoir titled “Incredible Journeys: Family Stories,” from which the foregoing account is excerpted.

Copyright © 2024 by Fran Kolesnikowicz.

****************************************************

The Beet Chip Infraction

© By Jen Parkinson

Legend suggests that when a child accidentally on purpose frees a tooth and tucks it under their pillow at night, someone or something known as “The Tooth Fairy” scoops up the fang and makes an exchange for change. Back in my day, a dime elevated one to the upper echelon of financial status among peers. Today, I’m sure that direct deposit supports this ancient barter system.

The beet chip tango al dente — Illustration © 2022 by Linda Arkelian.

Everyone has their own idea of what “TTF ”(acronym for The Tooth Fairy for social media aficionados) looks like. A Tinker Bell physique is common; but, this creature has also been depicted in books as a pixie, a dragon, some kind of rodent, and, in one scary instance, a pot-bellied flying man smoking a cigar.

TTF came to mind as I stepped up to the dental till to increase their bottom line and send mine plummeting. The last in my trilogy of visits, the time had come to pay the price of an unexpected crack. I chomped on a beet chip. A shift in the tectonic structure of a left side low molar was detected. Ah, shit. No physical pain fortunately, but something had to be done. Even though my dental life flashed before my eyes, I mustered up the courage to call the receptionist at the dentist’s office to book an appointment.

The next morning, I couldn’t locate that crevasse my tongue had found. I held a hopeful delight that perhaps I’d been mistaken. Better to confirm, as a less-than-24-hour notice fee would apply anyway. I walked confidently into the reception area anticipating a quick in and out, with assurance that the tooth was intact. The grumpy dental assistant guided me to an 8-by-10 cell sporting a recliner and a tray of ghastly looking instruments at the ready to hack at the chopper in question. As she positioned the drool towel, some poor soul in the next cubicle started to yell. “Ow, oh, owww. That hurts!” Her distress rattled me.

The dentist sneaked up from behind, his approach drowned out by the hullabaloo bouncing off the walls of this busy office. “I’m Doctor Freeze. I hear you have a cracked tooth. Been opening beer bottles with your teeth again?”

Hilarious.

“Nope. Beet chip.”

His foot initiated a chair recline as he flipped the switch of the miner’s lamp connected above the tiny binoculars covering his eyes. As blood rushed to my head, he said “Let’s have a look.”

This tooth had been repaired a few years back. An “on-lay” the installer called it, created to spec and slapped up against the remaining side wall of that molar. Food got wedged upon occasion. The fit left a bit to be desired.

The comedic Doctor Freeze sniffed out the fissure and in the blink of an eye, pried the artificial chunk off with his tiny crowbar. Shit again. $1200 flushed down the toilet. “Hmmm,” he said. “I’m not too sure what I’ve removed.” So, what did I originally pay for? I guess we’ll never know. No pain; but even though the nerve remained safely tucked away, the ongoing shrieks of my neighbour echoed through my mind. “THAT HURTS, hurts, hurts …”

“I’ll clean up the decay and build a temporary tooth, but you need a full crown.”

I couldn’t say, “Figures… I have no benefits,” fast enough. It didn’t matter now. He’d hacked out the majority. The path of no return had been forged, so I sat waiting for injected liquid to remove half my face from reality. This guy and his cheerless assistant worked fast. The X-ray triggered my gag reflex for a few seconds. The high-pitched drill squeal lasted for a couple of minutes, with the stench of burning decay (oh, you know that smell) fading only as fast as memory would allow. Temp-tooth was up and running in less than 30 minutes. Built, cemented, dried, and chew-worthy. Step one completed. Space age compared to my dental journey through the Sixties. Over the next four hours of the thaw, drop-cloth in hand during the ingestion of food or drink, I chewed the crap out of the numb part of my lip and bit my tongue just south of the frost line while eating something chocolate. A lesson to be had there perhaps?

Step two will be the prep work for the install of an artificial tooth. The term ‘crown’ is relatively new in my dental dictionary. I was eight or nine when my face voluntarily stopped a rock from hitting the school wall. Success in that heroic act resulted in two shattered front teeth, half a fat lip, and unhappy parents. After several agonizing fang-doctor sessions, two new caps flashed with every smile. A crown must be the same thing with a higher price tag. My hope is that he will not use recycled porcelain from a third-party vendor.

One week later, I’m back at the dentist’s office. The heat of impending doom should have warmed me. Only a degree above freezing in the waiting room on this summer day, the cold increased the involuntary chattering of my teeth — boosting potential cash flow for this business. The less time to anticipate danger the better, so I’ve no idea why I booked for 2:30 in the afternoon. A fifteen-minute delay in start time allowed me to rationalize festering fears. Last week’s repairs weren’t so bad. It took four hours to thaw out; but, there were no lasting painful repercussions, right?

The assistant to Doctor Freeze, boasting a happier demeanor this time, called my name, then asked, “How are you?”

I lied as we walked to the cell.

The doctor greeted me with a kind hello and a syringe full of viscous looking fluid. It’s possible that high doses of Vitamin C have power over whatever numbing agent filled that plunger — a theory, but the only thing I had done differently from the last visit. The area only slightly deadened, a direct hit closer to the site infiltrated the vicinity enough for the excavation to begin, but not before a bit of that foul-tasting liquid rolled down my throat, anaesthetizing all tissue in its path. Where’s that teeny vacuum and its operator when you need them? Doctor Freeze worked quickly, but not fast enough to beat the receding ice flow. The nerve hit contorted my face into the expression that only that kind of intense pain can elicit.

“The freezing’s gone.” I mumbled, just to confirm.

“That’s okay. We’re finished drilling.” Then the air from the blow dryer hit full throttle. Geeze Freeze!

The area now groomed, a glob of gummy material pressed into the crater created a perfect mold that once filled with cement, hardened in 30 seconds. A dash of glue, a quick, solid push into place and presto – a temporary nerve guard. In and out in 40 minutes — and two weeks away from the crowning achievement.

The days flew by.

“Jennifer?”

I looked at the receptionist. “It’ll be a few minutes. She’s getting the room set up.” Never having heard that excuse for tardiness before, any remaining colour drained from my face. Why would it take time to primp the room? Listening intently for any tool sharpening, I discretely shifted to the other side of the waiting area to watch for buckets, mops, or anything indicative of a major cleanup. Watching “CSI” can be helpful. Nothing suspicious to report. Good. The delay gave me a few minutes to attempt calming techniques learned while binge-watching Oprah and Deepak’s 21 Day Meditation Challenge. Breathe in relaxation, breathe out stress; breathe in—what are they doing in there, breathe out—should I make a run for it, breathe in—stay, breathe out—run, in—stay, out—run. On the way to hyperventilation, I stopped breathing and paced instead.

Eventually summoned, I stepped tentatively into the familiar cubicle, quickly scoped around for anything that looked amiss and once satisfied, slid into the recliner. Once again, dental guy sneaked up from behind. “No freezing this time. We need you to feel everything to make sure the fit is right.”

My best stink-eye shot at him saying “Yeah. I felt everything last time. Remember, Freeze?” A direct hit. He said “Don’t worry. We won’t use the blower to dry the area and we’ll be careful.” Skepticism abounded, confirmed by a weak nod.

How would the temp come off considering the adhesive he used? Two flicks with the pry bar and that thing popped like a champagne cork, leading me to wonder why I hadn’t eaten it at some point during its two-week residency. Expired glue? Comforting.

Next step? Slather the abyss with disinfectant, wait till it dries, and pop on the virgin crown.

“Okay, close.” Gingerly, I tried to drop the uppers to meet the lowers. The new unit sat two feet above the surrounding ones, so the filing began. He popped my custom-made chew toy in and out about 40 times. Each time it was in his hand more of that porcelain I’d be paying for turned to dust as he sculpted an upgraded version of the now defunct on-lay I’d been detached from. Yup. Even a slight breeze near that nerve set it off. Not too severe, but worth mentioning.

“That’s a good thing,” he said.

Maybe for you.

“The tooth is still alive,” he added.

No shit.

Finally, north met south for a comfortable reunion. Contact cement applied, the remainder of the original was safely interred under my new china chopper. Good to go in less than 30 minutes. Mumbling thanks, I bolted out to the desk, Visa in hand, and that’s the moment the Tooth Fairy flicked her way into my mind. This mythical figure of folklore may not have lessened the pain of losing teeth as a child, but the cash-back program provided incentive to tug at loose ones during waking hours so as not to swallow the possibility of a decent payday while sleeping. It’s the potential for financial freedom that ramps up desire for the legend to prove true. I know: baby teeth only. One could argue age discrimination. At this point, any chance of getting a kickback is worth a shot at confirming whether TTF exists. Am I right?

Something to think about, but here’s the thing. I don’t have the cast-offs to put under my pillow, and that is an essential part of the contract. Ah-ha! Where are those teeth? My brow furrowed as, in my mind, questions began to fire in rapid succession. Are adults getting ripped off? Could Doctor Freeze and TTF be in cahoots? Do you think he sells used teeth to TTF at a reduced rate? Is there a market for them somewhere in the universe? After all, TTF disappears with the last baby tooth and Freeze has season tickets to the Maple Leaf hockey games. Even a dentist can’t afford those without a supplemental income. If my notion is true, I think I just bought him a beer and a hot dog for his next appearance on Hockey Night in Canada.

Let’s see. The original broken tooth, the on-lay, the temp, and the next temp, all have value even with a depreciation rate based on years of service and usage. Hmmmm. Is the original worth more or less than the replacements? Well, another dentist would have profited from the first break, so that tooth is toast.

All of a sudden, I realized I’d been standing there staring blankly at the little Interac machine in my hand, all caught up in this bizarre fairy tale. Jolted back to the present, putting the conspiracy theory on hold, I punched OK to transact. Yet another version of left side low molar officially bought and paid for was now part of my mastication machine. Will it be impervious to the beet chip? Well, one can only hope.

Relieved that this adventure had come to a close, I took a deep breath. It was then that I caught a whiff of a faint, yet distinct aroma that had permeated the medicinal smell of the clinic air. As I walked towards the exit, mystified, it hit me. It couldn’t be, could it? Was that cigar smoke?

Jen Parkinson, a resident of Whitby, Ontario, has been writing short stories for several years. One of them is included in “Change One Belief,” a collection of writing by several contributors. She is currently working on her first book: “I Am Enough: An Experiential Guide to Monumental Change.”

Copyright © 2022 by Jen Parkinson.

****************************************************

Evelyn’s Stories

© By Pamela Williams

I. That’s Why I Asked You

They called him ‘One-eyed Charlie.’ Charles Taylor, the eldest son of a Blue Mountain farming family, was tall with thick dark hair. In a childhood accident, while using a fork to untie a knot in a shoelace, he lost the vision in his left eye. Though his eye looked normal, it was essentially blind. He wore glasses, though even with a large blind spot, he managed to drive. He attended dances at the community hall on the Mountain with his brother Hector.

“Would you like to dance, Miss Dawson?” Charles asked a roundish woman in a red flower print dress.

“No, sorry,” said Miss Dawson. “I’m very particular about who I dance with.”

“Well, I’m not. That’s why I asked you,” Charles shot back.

***********************

II. When Hector Married Stella

When Hector married Stella eyebrows raised around the Blue Mountain community.

Hector was funny, really funny. Stella was a looker. Hector had a glass eye. The original eye wasn’t healthy, so a surgeon removed it when he was a child. Stella had only one breast. She was born that way. The second breast just didn’t grow. She didn’t let that stop her. She created a second one out of cotton. She curled her hair by sticking tongs into an oil lamp.

Hector and Stella moved around a lot. When they moved to the Owen Sound area, they took a position on the Bachelor family farm. Stella did the cooking; Hector worked the farm. Stella liked the Bachelor family. Hector would often see Stella coming out of the farmer’s bedroom in the morning.

Hector was always sick. Though he smoked constantly, he lived to an old age. The couple had three children on that farm: Nelson, Mervin, and Doris.

Nelson went into the army. He was tall, blond, and good-looking. Girls liked him. He became a bulldozer operator. Later, he became a drunk.

Mervin went west to live in the foothills of the Rockies, somewhere in Alberta. He never came back.

Doris became a waitress in Owen Sound. When she got pregnant, the father didn’t want to marry her; but someone else did. Doris married when she was huge with child. Stella, pregnant herself, didn’t dare show her face at the wedding.

By this time, Hector and Stella had their own farm. Old Bill Taylor, Hector’s father, bought them a farm at the bottom of the mountain on the condition that he would live with them. Stella had a second batch of children. Her fourth child, Ruth, looked a lot like the hired man. Hector let him go.

Every time they had a new hired man, Stella would get pregnant. When Stella gave birth to redheaded twins, Hector divorced her for infidelity. Stella curled her hair and went out dancing.

***********************

III. Mrs. Pinch, 1939

Mrs. Pinch was a widowed teacher-lady. Her domain was a small Grade 3/4/5 class in the village of Thornbury on the edge of Georgian Bay. She ruled her room with a strap – and a yardstick. The yardstick she cracked against desks, or children’s heads, to get their attention. The strap was strictly for punishment.

Mrs. Pinch was a tall woman who wore black men’s Oxford shoes that were just a little too big – so there was room to expand into them as the long day of standing and patrolling the aisles wore on. Mrs. Pinch’s hair was dark with touches of grey. She wore black horn-rimmed spectacles.

It seemed to Mrs. Pinch that the problems began when she worked with the Grade Fours. Then the Grade Threes would get silly, and the Grade Fives would digress from their projects. And so, in turn, she strapped little Wesley for reading when he should have been doing math. And she strapped his smaller sister, Evelyn, for giggling when she was clearly instructed by Mrs. Pinch to wipe that smirk off her face. It never occurred to Mrs. Pinch that wee Evelyn, in Grade Three, had no idea what a smirk was – and, so, how to get it off her face was completely beyond her comprehension. What wee Evelyn did know was that whenever she smiled, or laughed, she was likely to bring on the wrath of Mrs. Pinch and the dreaded strap.

One small redheaded boy, Toddy Ray, absolutely infuriated Mrs. Pinch. She had just to glance in his direction to see some transgression. His fingernails were dirty, his hair uncombed, his shoelace untied. Everything about Toddy Ray was wrong – he was Irish. Each and every day Toddy Ray got the strap.

One morning, when Mrs. Pinch reached into her top desk drawer for her strap, she found it cut up into many small pieces. Her face darkened. She stood erect, holding a piece of strap in each hand, “Who did this?” she boomed. A horrible silence filled the room Children looked at each other all around the room.

One small voice piped up, “I didn’t do it. I couldn’t possibly have done it.”

Without her strap, Mrs. Pinch was forced to send Toddy Ray up to the big school principal. Toddy Ray’s mother was sent for. She came in her old clothes to speak with the principal. She wore an old-fashioned hat. After that, Toddy Ray never returned to Mrs. Pinch’s classroom. His family left town.

Copyright © 2021 by Pamela Williams.

Pamela Williams has found inspiration for her evocative photography in the cemeteries of Paris, Rome, Genoa, Milan, and Vienna – in the form of sculptures that evoke moods as varied as the imagination. Nominated for the Roloff Beny Award, Williams’ work appears on the covers of novels by Timothy Findley, Margaret Laurence, and Carole Corbeil, and it was the subject of a half-hour television special on Bravo and Vision. Williams ventures into prose with her new book, “Evelyn’s Stories.” The three foregoing stories are excerpted from that collection of short vignettes, which are based on stories her mother told her, spanning a period from 1906 in Glasgow to 2018 in Toronto. The book is available for purchase online at: http://www.interlog.com/~romantic/books.html

Editor’s Note: For our capsule review of “Evelyn’s Stories,” and for an exhibition of Pamela Williams’ exquisite photography, visit: https://artsforum.ca/books/books-in-brief

****************************************************

Father Time

© By Kathie Freeman

Illustrated © by Laurie Freeman

If my dad were still living, he would have turned 100 this year. Throughout our childhood and well into our adult years, my siblings and I affectionately referred to him as ‘Father Time.’ No one in our household could blame faulty clocks for tardiness

Illustration © 2021 by Laurie Freeman

because he made certain that every clock was in perfect working order and accurately set. I remember as a preschooler following my dad from room to room when daylight saving time or the return to standard time necessitated adjusting the clocks. He would tune in to a specific radio station that continuously updated the time. In my mind, I can still hear words that differed from the current coordinated universal time. Over and over, “CHU Canada, Eastern Standard Time: __ hours, __ minutes” played throughout the house until the clocks were reset. My mother seemed less than enthusiastic about this, likely due to beeping sounds that were the key to ensuring exact time. Although I had heard of Canada, I had not yet learned about its close proximity to the United States, and I imagined this wondrous place that broadcast precise time to be as remote as the North Pole. My reason for shadowing my dad on his clock-rounds was to listen to the intermittent French, which I thought sounded like poetry.

The last clock to be adjusted was the oldest and dearest. This mantle clock, made in Great Britain, was a wedding present from my maternal grandparents to my parents who met while studying osteopathic medicine in Missouri. They came home to Pennsylvania to be married in December 1954, and, upon their return to Kansas City, they moved into a little apartment in an old Victorian home. At that time they had three shared possessions: a card table, a cocker spaniel named Mickey, and the clock that they named ‘Asa,’ which means ‘healer/physician.’

Asa kept perfect time from 1954 until my dad’s passing in 2015. The clock stopped at 9:00 a.m. shortly after his death. We intended to have it repaired, but other expenses took precedence. Asa had always required delicate handling; and, because I was accustomed to dusting around the clock without actually lifting it, I continued the same practice. In the midst of preparations for Christmas 2020, I noticed that the second hand had dropped off and was cradled in the bottom of the glass bezel. For the first time in my life, I picked up the clock – and to my amazement found eleven dollars neatly folded beneath it. No one but my dad would have placed it there. At first, my sisters and I were reluctant to spend the money; but, in the end, we decided to purchase a lottery ticket. Happily, we won $20 and started a fund for the repair of our beloved Asa. Of course, the true gift beneath the clock was a father’s timeless love.

Kathie Freeman is a writer based in Pennsylvania. By day, she is a medical language specialist.

Laurie Freeman is a freelance artist based in Pennsylvania.

Copyright © 2021 by Kathie Freeman.

Illustration © 2021 by Laurie Freeman.

Editor’s Note: ‘CHU’ is the call-sign for a time signal broadcast on shortwave by Canada’s National Research Council, which took over that responsibility from the Dominion Observatory in 1970. The time signal, which is derived from atomic clocks, has also aired daily on CBC Radio One at one o’clock p.m. (lasting between 15 and 60 seconds) since 1939. That might make it the longest running ‘program’ on the public broadcaster.

****************************************************

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Pandemic – Part Two

© By John Arkelian

Illustrated © by Linda Arkelian

I. Easy Rider

I’ve never seen a motorcycle sidecar before, at least not outside an old newsreel or film from the silent era. They always seemed fanciful to me – the stuff of bygone times, if not fodder for

Illustration © 2020 by Linda Arkelian

Chaplinesque slapstick. But whimsy came to life one sunny fall day, when I was social-distancing with a friend at a ravine park. Down the steep incline came a motorcycle with sidecar attached. When the curious contraption came to a rest, its driver and passenger emerged with practiced dignity, gradually turning in place to gaze impassively into the four directions of the compass. (Had they come to make a fashion statement, to audition as models, or to reassure a doubt-filled world that mirages do exist?) The driver was a well-groomed man of indeterminate years, fashionably clad in designer-black. But, it was his passenger who caught my eye: man’s best friend was outfitted in goggles, a jaunty scarf, a canine body-suit that covered his torso and the upper third of each of his four legs, and white socks. As studiously nonchalant as his companion, he surveyed the scene without hint of emotion or intent, then rejoined his fellow traveler aboard their motorized conveyance for an unhurried egress from the scene – going back whence they’d come. Were they really there and gone in just two minutes? Once again, the pandemic left us wondering if we could believe our own eyes.

II. Confidence Game

Illustration © 2020 by Linda Arkelian

Although it long ago outlived its welcome, the pandemic has had the salutary effect of driving many of us to the great outdoors during the pleasant weather of summer and fall. A friend has found a daily sanctuary at the shore in Whitby, where she likes to feed the birds with bits of bread. One day, the chief beneficiary of her generosity was a one-legged gull. Its handicap elicited her sympathy as it bravely hopped to and fro for its meal. But, after it had had its fill, she could have sworn that its ostensibly missing leg suddenly emerged from a feathery hiding place, before this shameless panhandler calmly walked off to its next destination – with only the faintest hint of smug satisfaction on its face.

Copyright © 2020 by John Arkelian.

Illustrations © 2020 by Linda Arkelian.

****************************************************

Memories of Africa

© By Martha McMillen

A thesis: Africa changes us more than we can change Africa.

No one could have told me what would happen when I returned after eighteen years to America – the country I’d known as home. My travels as an international educator with the U.S. Peace Corps began in West Africa, where I got my start in Bo Town, Sierra Leone. Of course, no one can really come home again. The home I left behind had moved on without me and much was lost forever. Friends and family have changed. Some are strangers now; precious personal connections are severed. Even their memories of the past we shared have blurred beyond their ability to recall. Nothing is right or familiar anymore, and I feel unbalanced on my own erstwhile land.

I look at my street. It’s pretending to be the same; but, hiding behind those doors and curtains, subtle changes have taken place. While I was away, my clock stopped; but theirs has moved right along. New neighbors appeared. The houses stand stiffly in new coats of color. Different faces walk the streets. New roads lead to unfamiliar places. The children who used to come in and play dress-up in my Disney costumes are teenagers now. At Christmas, they proudly return to my front door, serenading me with their new teenager voices. My strange old house echoes softly in different tones of quiet.

There are too many changes all at once: In the developed world, there is food everywhere. I have to mention this, as it was this idea of being able to get food without waiting, food without danger, food without digging, or food I should be giving to someone else that felt so unfamiliar to me when I returned to America. It’s just too much. Seeing all this food, so easily obtained and abundant, food everywhere, made me physically ill. For months after my repatriation, I was unable to enter grocery stores, piled too-high, as they were, with everything. I went in, turned around, and came right back out. Of course, such over-abundance is the “normal” way of life in North America. But, what are our qualifications to be born on this so fortunate side of the ocean?

The only the comfort Africans managed to hang on to was their land. And yet, how little of it is left to them to manage. Only about a third of their continent is still untouched by strangers. In Africa, we found rutile (a mineral rich in titanium, which we dig for our space program), cobalt, and 40% of the world’s gold – in fact, about 30% of all of the minerals on the planet. We are still trying to reap those treasures from Africa, to remove them before we have to share them with others. How convenient it was – for us – to have found so many treasures in one place!

Let’s not forget the diamond wars, either. Since the Africans hung on to what they could during those conflicts, wiping out their tribal land, their customs, and their tribal worship never really worked. The diamond wars devastated them almost as much as trying to convert them to Christianity. But they have found their own ways around those intrusions. Yet, we never saw our “do-gooder” routine as a bad thing. It was just “winner take all,” wasn’t it? And now we have to live with it. That’s what’s been on my mind all these years. We had our chance to do good things and we have left it quite unfinished. But you have to give us credit. We never give up trying. In spite of all we do to change them, when you go back to Africa, you’ll see, it’s just the same. On the other hand, when I got back to North America, after working in many countries all over the world for eighteen years, nothing was the same. Actually, now, it’s worse, if that’s possible. Many of the special African people whom I knew are now dead, but they endure, as real characters who live on in my memories.

Martha McMillen is an international educator, whose 18 years of work training teachers in the developing world took her to such diverse postings as Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Egypt, The Philippines, the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and the Republic of North Macedonia (in what was once south Yugoslavia). A noted teacher, traveler, and raconteur, she is a long-time contributor to the pages of Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2020 by Martha McMillen.

Editor’s Notes: (1) Bo, also commonly referred to as Bo Town, is the second largest city in Sierra Leone, a country in West Africa. (2) Rutile is a mineral composed mostly of titanium dioxide.

****************************************************

Lunch with the Brits and Other Disasters

© By Martha McMillen

I don’t care for the kind of people we are meeting.

We are on a short Peace Corps break before beginning the work that brought us to Africa; but the place is full of foreigners – Germans, French, et al. They’re all on vacation in the much less expensive country of Sierra Leone. They have lots of money, and I don’t. The Brit’s house on the embassy compound is large and pretty, but the food is ghastly and the kitchen filthy. When Bart (the Brit) puts the left-over food on the floor for the dog, he lets her eat it out of a dish meant for people, and I wonder if I’ve been eating out of a dog dish all along.

Carolyn gets drunk and plays cutesy-coy all evening. Bart takes us to the private swimming pool, where Joern the Norwegian and Maggie from Seattle have a 2 a.m. swim. I am bored. Why don’t I like these people? I’d rather be home at a rehearsal. Is this all a rehearsal for something else?

I buy a large camel-hair rug or wall hanging from Mali today for 125 leones.* I guess I got ripped off. That’s what you get for buying at the Paramount Hotel. Maggie says, “I told you so!” I also bought a teddy-bear mud-print* and two large mud-print cloths for couch covers and drapes. Now I have a gift for almost everyone. The kids will dump them as soon as possible. They won’t care one bit about the provenance.

I hope they don’t mind if I use them for a year or so. I played with a cute little chimp today, and Maggie took my picture with him. We checked out of ‘the Y’ and came to the Cape Sierra Hotel. What a joke! This dump is on Lumli beach.* Nothing works in hotels here either. Go ahead: go anywhere. Nothing works. What did I expect? The air-conditioning, the hot water, and the fridge were broken, so we moved out into another hut-like hotel, where only the water and the lights didn’t work. Two out of three ain’t bad!

Maggie has left me here and gone to have dinner with Joern, the Norwegian. Something’s cooking there. She says she wants his gas stove for the Home Economics department at the college. What she won’t do for a gas stove hasn’t been invented yet. I think she just wants to light a fire in Joern. I am glad to be alone for a while. I couldn’t get down to the beach because of the barbed wire fence. Does that tell you something? Please let me get out of here alive. Government guys with guns are marching around everywhere – and smiling. I think that bothers me the most. Why are they smiling?

It’s Saturday, September 25th on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Yes, that’s the capital city, Freetown. One of my friends at home got mixed up and sent a birthday card to me on the 7th addressed to “Free Tours.” Oh goddess! I guess she thinks I’m on vacation. This is the beach from which the slaver ships loaded their cargo. Tribes from all over were captured, brought to this beach, and taken to the shores of America. They were captured by other tribes: an enemy village could get a lot of money from the Portuguese selling their neighbors as slaves. (Of course, this ubiquitous human trait lives on in every race.) Now, however, this beach attracts tourists from all over the world; so some of the most beautiful women in the world are going by on the beach all around me. Only the Americans are wearing their whole bathing suit.

Joern is working on a system of microwave telecommunication towers. He already set them up, but he can’t run them, due to a lack of diesel fuel. At least, I know where the fuel is. All he has to do is come to the States and suck it up off the beach. There’s always a big spill somewhere back home. Maggie and I are spending two nights here at the Cape Sierra at 45 leones per night for both of us. Carolyn and Joern made out last night and all morning; so Maggie, who left me here alone last night, comes back feeling rather in the way. Suddenly, my company becomes valuable once more. All the white and black people here are wandering around looking for someone else. It’s crazy, crazy, crazy!

Sunday morning, September 26th: I’m naked on the beach. Yes! Well, almost. I dared to take off my top and emulate the French and German women who come here every season. For them, it’s cheap; for me, exorbitant. Sorry to say, I’m glad that no one has paid any attention. to me, except for one little kid, who is about 16, who pets my bare shoulders and informs me he is an “official” guide who is willing to stay with me and show me the town. Wow! At last, an offer of companionship. I sock him. I hope I didn’t hurt him too much. After he manages to get up off the ground, I explain that touching women without an invitation is a big “no-no.” He is so embarrassed and angered at being struck by a woman that he quickly disappears. Evidently, he’s had other kinds of reactions.

It’s too bad I have to leave Freetown for Bo in the morning; but it’s time to start work and begin what I came here for. I take a last look in the morning. The water is deep green-gray and clouds are hanging over the mountains like a dismal shroud. It looks exactly like Molokai* in the distance, but here on the beach it’s beautiful. Not so hot – yet. Not uncomfortable, and the breeze is “fine all pas mak.”*

Fisherman with their wooden boat just came in right in front of me. On goes the bathing suit top. You prude! I’m going to see what they’ve caught. They hauled in lots of sardines of various sizes, one large sea bass, and some fish with a sword-like lower lip they call “pinch” fish. It’s the same here with all the flora and fauna. You point to a tree and ask a native, “Wetin dat?” The answer of course is, “tree.” They know absolutely nothing about species. But then, they can’t imagine why they would need to. Me neither. They don’t ‘need to.’ As long as they know cassava, rice, yaba, tomatoes, potato leaf, and fish, they’re fine, and that’s sufficient. Speaking of potatoes, Joern gave me my first taste of aquavit – a wonderful Norwegian liquor made from a potato base flavored with caraway. Aquavit comes from just north of Oslo. Carrying-on a two hundred year tradition, ships must come from Norway and cross the equator carrying the aquavit, which rolls around in the hold – which, it seems, is a mellowing process. At least, the Norwegians swear it tastes better that way.

Monday, September 27: It’s been a long hard day since Maggie and I got up at 5 a.m. to get a ride back to Bo with Rudy, a college professor from Bo. He came an hour late to start with, as he’d made a side trip to Njala University College. We got back to Bo Teachers College around noon. Close behind us is Carolyn with Joern’s private driver. I didn’t get any mail again for a week. Moving to BTC must have upset the delivery system. Or, maybe no one at home has time to write letters.

This place, this Africa, is mostly ugly and really filthy, except for the faces of the babies, the mountains, and my chorus. There isn’t enough soap in the world to clean up Africa. Actually, there is hardly any soap and that bothers no one I know of. Of course, if you have to walk a mile (or more) to find a brook for washing clothes, or spend food money for soap, cleanliness fades quickly in your mind.

I learned from the children that getting power (and I don’t mean electricity) is the overriding theme of life in the village. Cleanliness interests no one, because it’s costly and useless. I remember what the Africans told me about getting “the power” and how they must do it. It’s just too gruesome to tell about now. I think God will not smile on a country like this, if she is watching.

As soon as I arrive, the music teacher, Matthew, comes to get me. He is extremely agitated. I soon find out why. He wants me to teach two classes right away – now! So, I do. Thank Goddess for experience! So far, their entire repertoire consists of the Hokey Pokey, Three Blind Mice, Brother John, and some church hymns in books the Brits left when they departed. I can’t believe this. The Brits took everything, even the trains. They did. But, they managed to leave a few of the tracks.

Matthew is the teacher at Bo Teachers College to whom I am seconded. That means Matthew tells me what he needs, and I teach it. The question is: where to start? They have repeated the same songs and the same script for “Scrooge” over and over every year for all their past lifetimes. They have learned nothing new, because Matthew is at a disadvantage – lacking both materials and the ability to teach it. So sad, as this is true is for every “class.” Classes taught by Americans are a source of great amusement to African students. Americans ask questions, and expect answers. Americans speak ad lib. Americans draw pictures to illustrate things and are extremely entertaining. African teachers have no access to new ideas, paper, chalk, pencils, and, well, you get the idea; so, they are truly boring to their students. African teachers are warm, friendly, helpful, and need lots of help. God knows I try.

Martha McMillen is an international educator, whose 18 years of work training teachers in the developing world took her to such diverse postings as Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Egypt, The Philippines, the border region between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and the Republic of North Macedonia (in what was once south Yugoslavia). A noted teacher, traveler, and raconteur, she is a long-time contributor to the pages of Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2020 by Martha McMillen.

Editor’s Notes (see * above):

(1) The author taught in Bo for one year in 1983-84.

(2) “Mud-cloth” (‘bògòlanfini’ or ‘bogolan’) is a handmade Malian cotton fabric which is traditionally dyed with fermented mud.

(3) The “leone” is the currency of Sierra Leone. In September 2020, one leone is worth 0.00010 U.S. dollar.

(4) The beach described by the author seems to have gone steeply downhill in the years since her posting to Sierra Leone. Lonely Planet.com has this to say about present-day Lumley Beach in Freetown, Sierra Leone: “This wide sweep of beach has lost some of its atmosphere since the 2015 demolition of dozens of bamboo and thatch food shacks, and the numerous, ugly construction projects lining the beach road don’t add to its appeal.” Writing in 2013, a Canadian contributor to Trip Advisor.ca said, “Anyone who has spent any time on the beach in Freetown will know that on first view you have a lovely beach, but upon closer inspection what lurks is not so lovely. Medical waste from ships dumping garbage offshore lines the beach and floats in the water. There is also human waste from small villages within the city which do not have facilities and use the beach. Carcasses from animals float freely, garbage floating from the city itself make for treacherous conditions. No swimming and when walking the beach, shoes are a must in order to avoid potential syringes from medical waste. Safety first as there are characters intent on opportunity as well, so never go alone.”

(5) “All pas mak” is an expression in Krio, an English-based creole language spoken throughout Sierra Leone. It means “the breeze was great over all.”

(6) Molokai is the fifth largest island in Hawaii.

****************************************************

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Pandemic

© By John Arkelian

I. Mr. Potato-Head

I’m not much use in the kitchen – or in a grocery store either, apparently. During the Great Stay-at-Home Seclusion born of

Illustration © 2020 by Linda Arkelian.

2020’s global pandemic, I drew the short straw, as the youngest of the three (but not by much), to make weekly excursions for foodstuffs and other necessaries on my parents’ behalf. On one such occasion, I was tasked with the mission of finding (among other things) “some regular, cooking potatoes.” Well, truth be told, I very much doubt that I have ever bought a potato in my life, as much as it may pain my forbears from the Emerald Isle to hear it. But I seized the opportunity to prove my mettle, undaunted by the novelty of the task. And, sure enough, I correctly identified the spud in question (known in the local grocer’s parlance as ‘yellow potatoes’) and proudly presented my find to my mother, in her esteemed capacity as Head Chef. Her reaction was bemused, her question rhetorical: “What am I supposed to do with three potatoes?” Assigned to find “some,” I selected three (one for each of us) and thereby confirmed the chef’s latent suspicion that I was unlikely to be a wholly satisfactory shopping surrogate.

II. A Case (or Two) of Mistaken Identity

During a pandemic, you can’t always be sure who you’re dealing with.

Day One:

On the last weekend before the official shut-down of society in mid-March 2020, I heard the doorbell while I was lingering in bed listening to a radio program on my beloved CBC. It was 9 a.m., but I didn’t feel guilty about being lazy, since it was Saturday, after all. By the time I got downstairs, there was no one at the door. Two hours later, I was still in my pajamas, but this time I was downstairs reading the newspaper. The doorbell ran again. I pulled my winter parka over my pajamas to preserve my modesty. A man was there. Without introducing himself, he said, “Since there are ‘older people’ living here [I furiously hoped that he wasn’t including me in that category] and since older people are supposed to avoid public places due to the virus, we’d be glad to help if you need groceries.” I was guarded in my response, as I had no idea who the fellow was. I replied, “I’m sorry, but I don’t know who you are.” His tone changed on a proverbial dime. Hitherto solicitous and friendly, he was downright peevish as he exclaimed, “But, I live right next door!” I was mighty embarrassed, though, to be fair, they’ve only lived there a year or so, and I’ve only seen him once or twice – from a distance, briefly, and without the heavy winter apparel.

Day Two:

The next day, on March 15th, I reluctantly took my mother to the grocery store. (It’s something my father normally does, but he had been temporarily felled by a flu or a bad chest cold.) I urged her to let me get the groceries (which, in fact, I’ve been doing ever since then), but she insisted on going herself. (Who knows? Maybe she had a premonition that I could not be relied upon when it came to potato-hunting.) The first section was the produce department, where, among the vegetables, I saw a man whom I thought might be the very neighbor who’d been at our door the previous morning. I remarked to my mother, “I wonder if that’s the guy from yesterday?” Although she has never met the man next door, she somehow knew his name. So, when he passed us, she asked “Are you Phil?” He replied, “No, I’m Jerry. I live next to John.” Then I piped in, saying, “But, I’m John; so wouldn’t that make you Phil?” Perhaps supposing that simple repetition would make everything clear, he again said, “No, I’m Jerry, and I live next to John.” So, I tried a different tack: “Well, we’ve been through that already. Whatever your name may be, was it you who came to our door yesterday?”

There’s an axiom that maintains that “the third time’s the charm,” and this man of few words clearly hewed to that belief, repeating his mantra one more time, albeit in openly exasperated tones: “No, I’m Jerry, and I live next to John!” Well, it finally turned out that his name was Jerry, and that he did live next to John – but that I wasn’t the John he had in mind. (The mayor is named John and he lives a few doors down.) The guy in the grocery store is a neighbor – from across the street and two or three doors down. Though we’ve never met him and didn’t recognize him, he knew who we were, though he had a peculiar reluctance to be clear about his meaning. The end result is that in the course of just two days, I unwittingly managed to convince two different neighbors – one named Phil, the other Jerry – that they’d come face-to-face with an unreconstructed ninny. And the pandemic has more than enough of those already.

Copyright © 2020 by John Arkelian.

Illustration © 2020 by Linda Arkelian.

****************************************************

“COVID, Manon, and Me”

© By Josée Legault

© Illustration by Linda Arkelian

“Can a fish catch the virus?” “When do I get to go back to school” “I’m tired of not seeing my friends.” “Why don’t we go to the movies anymore?” “When are you going to be finished writing your column?” These questions sound like they are coming from a

Pandemic indignities – Illustration © 2020 by Linda Arkelian.

child, right? They are not. These questions are just a few of many coming from Manon, my 57-year-old little sister. She is intellectually disabled, you see, and I’m her caregiver. I myself am 59.

I’ve been my sister’s only caretaker since our parents passed away in the mid-1990s from cancer. In the years since, Manon spent some time in a group home. But six years ago, she moved in with me full-time. Then, last fall we came to a new arrangement: half-time at home with me and half-time in a new residence. But in March, with the COVID-19 crisis looming, anticipating that the government would put all residences for the disabled and the elderly under lockdown, I decided to bring Manon back home – at least until the crisis blows over. Now, of course, it looks like we’ll be together for many months. So welcome to quarantine with a disabled person.

Because of the pandemic, many families just like ours are stuck inside. All families are unique, of course, but our common denominator is that we’ve lived with social distancing long, long before the arrival of COVID-19. There are few things that distance you more from the rest of society than living with and taking care of an intellectually disabled adult. Your friends and colleagues – also in their 40s, 50s and 60s – seem to have normal lives, with grown children who have moved out, active social lives, travel, and so on.

My arrangement with my intellectually impaired sister, which takes up enormous amounts of time and energy, is seen as something of a bummer that puts a damper on normal activities: you don’t get to go out as much. You can’t really travel because respite is barely available. In other words, your life is so different from everybody else’s that even the oldest and closest of friends forgets you. You become a full-time outsider. So how’s it going now in confinement because of the virus? Well, here is a peek into what’s happening at my place.

A lot of repetition

Because my sister has such a short-term memory, I have to repeat the same hygiene guidelines a couple of dozen times every day. “Wash your hands,” I keep telling her every half-hour or so, explaining all over again exactly how she is supposed to do it.

Fighting boredom

Because Manon is cut off from her regular activities, she feels lost; so I have to find things for her to do. When I sit down to write my columns, I have to ask her to take care of herself. That is basically ‘Mission Impossible.’ Manon doesn’t know how to entertain herself, so I sit down in front of the keyboard, I get up, I sit down, and once in a while I get a break when she watches TV.

Daily mass, circa 2020

Every day, at 1:00 p.m. sharp, Manon and I sit down to watch Quebec Premier François Legault’s televised press conference. It has become a new version of going to church for many Quebecers. “I love you Mr. Legault!” my sister shouted at the screen the other day. And then, bang! Full of fear, she shouts, “Stop talking about the virus! What you are saying stinks!” Like everyone these days, Manon’s emotions are on a roller coaster.

Looking for outlets

I only shed tears when I am on the telephone with a couple of very close friends. We try to cheer each other up with jokes and funny stories. Still, someone I thought was a good friend – and ironically, who lives with her intellectually disabled daughter – called me this week to tell me I was “hysterical” and “too intense” because one evening I dared to talk about my anger at how unprepared the Western nations were for a pandemic. Oh well, such is life.

Yes, life with Manon in confinement is a challenge. I remind myself that isolation is a challenge for many people. It’s just the world we’re living in right now. Happily, Manon is very artistic. At home, she has every possible tool to draw, paint, play music, et cetera. She especially loves painting flowers, trees, houses, suns, and stars. She’s painted many portraits of us together. She makes fabulously original birthday cards for me and our friends and neighbours. They are naïve and child-like but always happy, optimistic, and bright.

Walks, on high alert

Taking my sister for a walk in the best of times is always an adventure. Now, our walks are much more complicated. Manon is aware that she needs to stay away as far as she can from the virus. She is terrified. So no matter how much I keep her two metres away from other people and tell her that will keep us safe, she stays on full alert. Whenever she sees someone approaching, she grabs my hand and tries to leap out of the way. Flying through the air, we must look like a strange team.

Plagued by fear

A caregiver’s fears never disappear. And now, of course, there are new ones. What would happen to Manon if I get sick? Worse, what if I die? These questions plague me. But even when both of us are bone-tired and anxious, we somehow manage to pull ourselves together. I tell Manon that we are two soldiers, and we are going to win the battle. “We won’t give up,” Manon keeps repeating. It’s good advice. She’s right.

Letting in the light

Things are tough now, but they will get better eventually. We just don’t know when. Manon gets out the board games and we play ‘Trouble.’ We crank up the music and we dance and sing. We even exercise, stretching our arms and legs so our hearts get pumping. After supper, we settle in and binge on TV. We both love the shows about home renovation. We love watching walls getting knocked down, kitchens getting new counters, windows letting in more and more light. It is like better worlds are being constructed right before our eyes. If only. At bedtime, before I close my eyes, I thank God that Manon and I are doing just fine. I make sure to add another special thank you – for ‘Home & Garden TV.’

Josée Legault is a journalist and author and a political columnist for the “Journal de Montréal.”

Copyright © 2020 by Josée Legault

Editor’s Note: “COVID, Manon, and Me” was broadcast by CBC Radio’s estimable “The Sunday Edition” on April 19, 2020. It is reprinted here with the permission of its author.

****************************************************

The Bellydancer

© By Barbara A. Vance

Art © by Denise Wilkins

The moment had come and there was no longer any tangled

“Lady Butterfly” (acrylic) – © 2019 by Denise Wilkins.

heartbeat to linger upon. The unseen visions that filled the space behind her eyes fell away as she looked into the unknown. The breath that had been suspended in her chest was no longer captive; and she was aware of forcing herself to inhale and exhale. Oh quivering heart… screaming… screeching. What have you done? No longer able to get out! What have you done? No one could hear her torment; but she felt the icy flow of her blood in every limb and muscle.

It did not matter that she had prepared to the point of exhaustion. Her mind was filled with utter fear rather than an ability to remember. Oh, how that made it worse – falling into the precipice with only the hope of a miracle to save her. As she watched the others – so calmly, yet briskly, taking care of their duties – her head whirled frantically, wishing that she could be them instead: so much easier, so much less demanding. Why did she seek this out at all?

She was different from the others. She knew that. The others were carefully molded creatures of exquisite beauty. They floated about effortlessly, gilded in their perfection. Yet she found something within that refused to be fettered. She tried their way, so many ways; but, she would always fly outside of the borders of perfection. The weight of disapproval had never lifted; and now she would be exposing her shame to the world. But the fire that burned in her belly would not extinguish. She felt truly alive in this space of herself; and the hunger to reach inside drove her in search of answers.

Lifting her eyes, she looked into the faces of those who had come. The music struck her ear first. As she opened her heart, the music plummeted into her soul. Her emergence was swift, grabbing hold of the very first drumbeat. And then the liquid oil of her aroma began to flow. Saturating the entire space, she turned across the floor

“The Bellydancer” (photograph) – © 2019 by Barbara A. Vance.

revealing what would always be a mystery. The still room fell in awe, mesmerized and drawn into the mystery of what she held captive in each heart in that moment. No longer looking at her, they became the canvas, yearning for her to caress them, mark them, strike them, touch them, however she desired. Each undulation, each step of turned-out ankle, each hip movement, was her brush, and she choose her pigments – sometimes with deliberation, sometimes with total abandon.

Her passion was raw yet refined, her mastery ineffable; her sensitive embodiment of a life that was at once fully lived yet still to unfold drew her watchers into herself, breathlessly desperate to live out of her. Much too soon, it was all over. She was utterly spent and done. She had said all she could this day; anything more would be redundant, destroying the intimacy so freely shared.

The floor lay barren once she left with only the grit from the bottoms of her feet and small pools of her precious sweat here and there and her bright, earthy aroma lingering. The room emptied quietly with only the common rustlings of preoccupied busyness and the lights darkened abruptly at the last close of the door. Each had their own way to go, and as they did, they took a piece of her heart with them from the moment in which they lived in it.

Barbara A. Vance is a poetic artist who uses all her senses to experience life as she lives it. Be they ordinary or simply extraordinary, she translates those experiences through her inner world with an inimitably personal touch. Her sorrows and her joys, her losses and her triumphs, are chronicled in her heart and recalled in stories that aspire to the startlingly revelatory.

Denise Wilkins is an artist, photographer, and graphic designer based in Durham Region. Her art is on display in Whitby’s Nice Bistro and at the Open Studio Art Café in Pickering. See more of Denise Wilkins’ work at: http://www.lifeartdesigns.ca/

Copyright © 2019 by Barbara A. Vance.

Art © 2019 by Denise Wilkins.

****************************************************

Two Women

© By Martha McMillen

I. The crawling woman (Egypt)

This image blots out every other thought in my mind. She won’t go away. Ever.

It was in the market place of the Khan el Khalili that I first saw the woman who was able only to crawl among the populace on her hands and knees. She crawled past others who accepted her as if she were just another basket or cart of vegetables. Since she was always there, she appeared to be no more than that.

The Khan is an amazing place, ever changing, yet changeless. The people there are busy, yet timeless. The bearded ones play their board games and drink coffee. Women shop. Some men work their magic with gold and silver for the many foreigners who come to be amazed and amused. The odors of spices and humans, the raucous call of the muzzain, and the endless lines of people shuffling past the stalls keep the place feeling like a bee hive – whose denizens are always buzzing, yet slowly, purposely, taking their time, as if it’s always going to be that way.

I don’t know if the woman was born a cripple, or if someone saw to it that she became one. Every man knew that she was easy to catch. The child she bore, no man would admit to fathering. How she managed to give birth in the Khan el Khalili, I’ll never know. How strange a place to deliver an infant girl… When I saw her, the tiny creature was attached to her mother’s neck, and she clutched the mother’s hair with a desperately instinctive grasp, knowing even then that to let go was to be lost.

Day by day, the crawling woman arched and bent, wriggled and scrabbled around the market, stopping here and there to rest; and while taking the baby down to nurse, she reached up with one boney arm to beg. I couldn’t watch, and I couldn’t stop watching. It was unimaginable. Over the years, I can barely stand my own imagination’s visions, thinking of the time she spent and how she spent it keeping the infant alive. How did she do it? How long was she able to do it? If she died, what would have been the life of such a child?

I told you in the beginning that the image won’t go away. It won’t, I promise.

II. The sacrificial woman (Bulgaria)

The other woman comes to me in dreams. But her story was first told to me when I came to visit the convent and abbey in the countryside just outside of Kazanlak. It is the story of the sacrifice of a real woman, a nun, who gave her own life away. Her act was the affirmation of her faith. It was her whole life’s purpose. In making this sacrifice, she imprisoned herself in a stone niche in the outer facade of the abbey and instructed that they shut the iron grill that covered the niche from top to bottom, pressing her in tightly to immobilize her body. As she stood there, a small drip of water was forced into the space above her head, and slowly, slowly, it dripped away by the hour and the day and the week – for how long I can’t imagine. At first, the water appeared to do no harm, and then, very slowly, each drop of water felt as if it pounded into her brain as surely as a nail into a crown of thorns. Did she scream her way, I wonder; or was it a silent scream that preceded her death? I know she gave it as her greatest gift.

Martha McMillen is a world traveler, esteemed educator, writer, and raconteur based in Chicago. She is a longstanding contributor to Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2014 by Martha McMillen.

****************************************************

“No Business like Show-Business… in Stara Zagora”

© By Martha McMillen

© Illustrated by Dennis Stillwell Martin

3:49 p.m.

The performance is supposed to begin at four o’clock. I wonder if I am in the wrong place? Only two of us are seated in the audience. A guy comes in with a small electronic keyboard and starts looking for a light so he can see

his music. An ominous looking metal box appears, along with a one-by-two foot lighting board, with four hefty guys huffing and grunting disproportionately to the size of their load. They set up on tables in front of the stage. Another guy, over on the side, keeps playing with his video light and blinding the three people who have arrived; so they decide not to be seated after all.

3:57 p.m.

I’m excited. Three minutes to show-time! This is supposed to be a serious play about the origin of the universe; but, for some reason, eight high school kids appear on the stage and begin rehearsing Bulgarian folk music in the jazz idiom. While they are rehearsing, the microphone technician tries out the four giant mikes in turn, speaking loudly enough to drown out the jazz rehearsal. He is successful. Rehearsal is finished.

3:59 p.m.

One minute to show-time. There are now four people are in the audience – including me. The sound man tries to drive us away with more-than-the-eardrum-can-bear, pumping the volume of some very heavy metal up to excruciating decibels to make certain we know that there really is a sound system here.

4:15 p.m.

Fifteen minutes past show-time. Now there are about thirty people in the room. Some are seated. The rest are greeting friends and touring the stage areas. Some are bringing their espresso in from the lobby bar and looking for tables. No one seems in any rush to start a performance. Could it be that I have come on the wrong day? My reading of Cyrillic does need work.

4:31 p.m.

Someone comes out to announce something very important in Bulgarian, but I can’t make out what it is. No one is listening or responding to him, so I guess that the announcement is not about fire in the theater, cancellation of the performance, or running out of espresso. He just keeps speaking amidst all the chaos, and nothing is going to stop him. It must be okay, because he keeps smiling.

Two new guys with video cameras walk in front of the announcer and start talking loudly as they point to the audience and wave to friends. They aren’t drawing as much attention as they would like, because they are competing with the speaker on the stage, the sound man twisting his knobs, members of the audience walking around talking to each other, and the keyboard guy’s continued search for a light.

The video reporters saunter across the stage and start filming the thirty people who are walking and talking in the audience; and then they find me! The lights are blinding. A foreigner always makes for an exciting shot, but there’s no use overdoing it! Then, the videographers get into an argument with two members of the audience who object to being left out of the movie in progress. They all stop, wave arms, shout, and stomp around the apron. Everyone is a director. The camera guys, laughing, just walk away from the offended patrons, leaving them to carry on their diatribe about being left out of the film. But they don’t go far, returning to cross the stage regularly every two minutes. Presumably, shooting in this manner this is more fun than standing still. I wonder why they don’t just wait to shoot the play, if it ever appears.

The man who is making the speech comes back with renewed vigor and tries to be heard above the din. Plucky little soul! I find out from a friend that he is the head of the jury who will judge the acts in this three-day festival. Just think of it. Three days! He and a new friend on stage now do a five minute spiel, and the audience begins to suspect that something is going to happen. They begin to sit down.

4:45 p.m.

Something does happen. Fifteen to twenty people enter the room and begin rushing around. Some have furniture. Some have props. Some have pieces of sets. Three of them are looking for a lightbulb for a lamp which is now hanging down between the legs of a tall ladder placed on center stage. Sadly, they unscrew an obviously dead light bulb. They pass it around from one to the other shaking their heads at such workmanship. Someone says it probably came from Poland. Someone brings on a wooden cross with strings attached to a plastic tent so that God can come in out of the rain.

4:55 p.m.

I have been here almost an hour. There is still no sign that the theatrical performance is about to begin. The guy with the lamp poses on stage dramatically and sighs as he gazes longingly at the ceiling fixture in the center of the room. If only he could reach up there! Hanging up there in a tantalizing array of color are at least 65 light bulbs. A veritable treasure trove! However long he gazes, the replacement bulbs are still out of reach. What to do? He tries his broken bulb again. Now he takes the lamp apart piece by piece. Maybe it’s the lamp! The pieces all fall out on the floor. People begin leaving to get a snack in the lobby.

5:00 p.m.

Someone has found a light bulb! Oh, how grateful I am to see this sign of progress. The lamp is restored and now actually works! The original searcher is gratified so much that he tries it out ten or twelve times for the audience, gives us all a real thumbs-up sign, and retreats. He is smiling.

5:08 p.m.

Show-time! God and a friend show up with a terminal case of overacting. I know in a very short time that there is no cure. In spite of all of their efforts, there is no audience reaction during the first half hour. Most of the patrons are drinking or talking to each other and aren’t giving God a second thought. God’s friend turns the infamous lamp on God, hoping this will call attention to the show, but since the bulb is so weak the overhead stage-light masks the effect. No one can tell if the critical spot-bulb is on or not. The lighting guy is basking in his success. After all, it is working! The sound guy is jealous beyond words.

God keeps drinking something from a bottle in a paper bag and getting more and more disturbed, if that is possible. Now God is trying to retch up something significant – or to force it out the other end. I think it’s the Earth.

I don’t want to be here anymore. Three hundred years under the Turks and thirty years under the Russians have taken their toll.

Martha McMillen is an educator who has worked in many different parts of the world.

Dennis Stillwell Martin is an artist, musician, and teacher; he is also a longstanding contributor to Artsforum Magazine.

Text © 2005 by Martha McMillen.

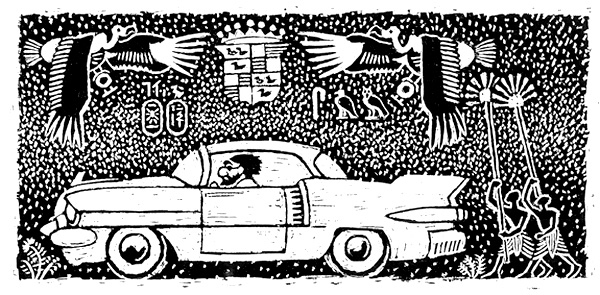

Illustration © 2009 by Dennis Stillwell Martin.

Editor’s note: The city of Stara Zagora is situated in central Bulgaria; as of 2011, it had a population of over 138,000 people.

Illustrator’s note: The author refers to “a lamp hanging down between the legs of a tall ladder…” This forms the basis of the “A” symbol in the drawing: It is the symbol of anarchy, which is exactly what this account of showbiz describes.

*****************************************************

Our Wonderful World

© By Karen Zey

I am stuck in front of a row of sagging book spines on a bottom shelf. They’ve sat untouched for years: 18 reddish-orange volumes of Our Wonderful World, An Encyclopedic Anthology for the Entire Family, published in 1957. I’m in the midst of one of those virtuous home projects: a day of de-cluttering. The musty pages contain mostly defunct information—yet I can’t bring myself to throw them out. Just a glance at the faded gold titles takes me back to the childhood experience of expanding my world beyond the neighborhood where I grew up.

In the pre-Google era, books offered the answers to many questions. If you wanted to research anything foreign or scientific for a school project, you put on your shoes and walked to the library. If you wanted to explore the world beyond the little suburban house where you lived, you sprawled on the couch on a rainy afternoon and pored over page after glorious page of Our Wonderful World.

Volume 5, page 4: “We live at the bottom of an ocean of air, which in many ways is like another ocean of water. The weight of the hundreds of miles of air upon our bodies can be compared to the weight of the ocean water upon fish who live in the depths of the sea.”

In 2004, A. J. Jacobs, an Ivy League graduate and magazine editor, published a book about his quest to read the entire Encyclopedia Britannica. He documented his quixotic feat in his New York Times best-seller, The Know-It-All: One Man’s Humble Quest to Become the Smartest Person in the World. It was an intellectual enterprise, a reflection on knowledge by someone already immersed in the world of letters. In 1962, J.W. Baxter, a high-school graduate and salesclerk at Mitchell Photo Supply in Montreal, wanted to nurture a quest for knowledge in his three young daughters, including me. In our modest bungalow in Pierrefonds, there was little reading material beyond the evening paper, Reader’s Digest and a few Nancy Drew mysteries. Dad decided we needed an encyclopedia set.

One Sunday morning, he asked me, the eldest, to go with him downtown to pick up a present from a work colleague: a second-hand set of encyclopedias called Our Wonderful World. I was thrilled. A car ride beyond my neighbourhood was a major outing, and time alone with Dad was precious. The store’s bookkeeper, Eunice, lived in an old apartment on Sherbrooke Street, right in the heart of the city. Dad referred to her as a “spinster,” from a well-to-do family. The word sounded regal to my nine-year-old ears. I put on my Sunday-best dress, clipped my hair back with barrettes, and listened to his gentle reminders about good manners when visiting.

I remember sitting stiffly on the edge of Eunice’s blue brocade chesterfield, keeping my hands nestled in my lap, and gazing with awe at the strange surroundings of that downtown world. The high ceilings, the curlicue legs of the antique tables, and the swirls on the pastel patterned rugs were all so different from the brown wall-to-wall and chunky shapes of our own living room. I knew we were getting something special, and that these volumes would reveal things that I hadn’t yet imagined. I felt a burst of love for my dad for taking me along on this city adventure, and for thinking I was smart enough to read an encyclopedia.

Volume 15, page 109: “No true frog has the poison glands, or parotoids, found on the shoulders of true toads.”