“Servant of the People”

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

Courtesy of Kvartal 95 & Vision TV.

“Servant of the People” [“Sluha Naroda”] (Ukraine, 2015-19) (B+/A-):

How utterly strange it feels to watch a television series about a neophyte Ukrainian president who is determined to overcome heavily adverse odds, played by the very man who is now the embattled president of that self-same nation in real-life. But before he became the indomitable president of Ukraine in the real world, Volodymyr Zelenskyy played one on “Servant of the People,” a political satire made for television. His fictional character, Vasily Petrovych Goloborodko, is an earnest, idealistic high school history teacher who finds himself unexpectedly elected president in a country which is rife with corruption. Goloborodko dares to see things as they might be, rather than as they are; but, his idealism is never played for laughs. He may be new to politics, but he is by no means naive. It is refreshing (and, yes, even inspiring) to have the lead character played

Yury Krapov, Olha Zhukovtsova-Kyiashko, Yevhen Koshovyy, Olena Kravets, Stanislav Boklan,

Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Mykhailo Fatalov, & Oleksandr Pikalov in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

straightforwardly as a man of integrity, instead of being made fun of by the scripts for naiveté. For the fictional president, “The success of any enterprise rests on three pillars: hard work, honesty, and fairness.”

It is manifestly unfair, of course, that the lion’s share of the country’s rich agricultural and industrial resources benefit the very few at the expense of the many and that nepotism is the prevailing order of the day. Not even Goloborodko’s close kin are immune from the ubiquitous temptation to benefit from their connections: his father and sister, in particular, have high hopes of gleaning everything from upscale home decor (the more overtly ostentatious and gilt the better) to elevated status in the workplace on the strength of their kin’s new coattails. But the new president is having none of that. He eschews chauffeurs, limousines, bodyguards, and official residences, continuing to live with his parents

Volodymyr Zelenskyy in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

in their somewhat dowdy flat. He takes the bus, or his bicycle, to work. In the first season’s engaging opening credits sequence, we get a tour of Kiev by bicycle. (Seeing that lovely city’s combination of modernity and history has resonance in the here and now of 2022, as it, like the rest of the nation, finds itself under savage and lawless attack by the autocrat next door.)

A trio of powerful oligarchs call all of the shots, owning everything worth owning — including every member of the national legislature. Initially, these self-appointed overlords are mostly faceless: seen only in extreme closeups of bald pates and contorted mouths, they at first come across as deliberate caricatures. Later, recast, they get more definition as individual characters in their own right. But, their objectives never waver: “We need to know his price, how long his leash is… We need an obedient president.”

Goloborodko dismisses the army of hangers-on whose presence on the employment rolls inflates the cost of administering the state; at his first press conference, he candidly tells the assembled reporters that he doesn’t know the answers to all of

Kateryna Kisten, Viktor Saraykin, Nataliya Sumska, & Volodymyr Zelenskyy in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

their questions, promising to rectify his own lack of preparation; and he instinctively speaks from the heart during his first address to the nation, preferring direct honesty to empty platitudes. And he quickly outmaneuvers his suave handler (the country’s prime minister) by finding people he trusts to run key branches of government. They may be inexperienced, but his handful of schoolhood friends (including his ex-wife) can be trusted because they are people of integrity. Indeed, each of them rejects attempts to bride them. One, a captain in the armed forces (Oleksandr Pikalov as Ivan Skorik) whom Goloborodko makes Minister of Defense, rebukes his shrewish wife when she lambasts him for rejecting a huge bribe: “Once you take it, the dirt will never come off.” He gets another good line (with universal applicability, alas) elsewhere: “The country’s fine. We just have a lot of jackasses.”

The series is a bit of a chameleon. It is fueled in part by situational humor; but it is the ensemble of characters who really propel it. There is deft social and political satire. There are moments of broad comedy, chiefly represented by Goloborodko’s father, by his sister, and by his choice for foreign minister (a clownish small-time

Volodymyr Zelenskyy in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

actor who works in television commercials). None of that unabashedly unfiltered trio are known for their tact. There are moments of farce (in the chases, disguises, and stalling tactics from the film adaptation and related second season). There is a unsettling feint into much darker territory with a seeming mass betrayal of the president by friends and family. There is some serious social commentary (as in Season Three’s prison scenes). Season Three gets somewhat didactic, with a future classroom in a stable, prosperous, and graft-free Ukraine reflecting back on the pivotal events of Goloborodko’s (and our) time. And the show ends on a call-to-action that practically breaks through the proverbial ‘fourth wall’ with its applicability to the real world.

The three seasons of “Servant of the People” are each distinct in tone and situation. The first (in 2015) has the well-meaning neophyte in office. It is Eastern European kin to the estimable 2006 BBC series “The Amazing Mrs. Pritchard” (starring Jane Horrocks) and to Frank Capra’s classic 1939 film “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.” Each of those productions involves a decent and honest person who finds him or herself in the halls of power, surrounded on all sides by those who are cynical, manipulative, and self-serving. The second season of “Servant of the

Yury Krapov, Yevhen Koshovyy, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Oleksandr Pikalov, & Olena Kravets in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

People” (2017), which is subtitled “From Love to Impeachment” (and which coincides with the plot of the 2016 film adaptation), combines three disparate elements — an unlikely buddy road-story, a truly funny farce (more on that later), and the emergence of a very realistic, very adept, very treacherous new villain. The third season (2019), subtitled “Choice,” is very different from what preceded it, devoting recurring scenes to the future’s perspective on the present. It gets didactic at times, but it also manages in its flashbacks to ignite an optimism, resilience, and sense of hope which go beyond their television series setting and into the real world.

A film adaptation of the series was released in 2016 under the title “Servant of the People 2.” Much of it was recycled into the television version’s second season. The movie version was nominated for Best Film, Actor (Zelenskyy), and Supporting Actor (Yevhen Koshovyy) at Ukraine’s Academy Awards (the Golden Dzygas).

Volodymyr Zelenskyy keeps us watching (and believing) as Vasily Petrovych Goloborodko. He radiates integrity and resolve and has an ineffable charisma. (His bedroom in his parents’ flat has a small bust of Napoleon. Is it simply because

Volodymyr Zelenskyy in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

he is a history teacher? Or is it a playful inside joke, since Zelenskyy portrayed the French emperor in the 2012 movie “Rzhevsky versus Napoleon”)? Stanislav Boklan is a treat as the suave prime minister Yuriy Ivanovich Chuiko. He’s an unrivalled master at political manipulation, and, while he is certainly part of the problem, my goodness, he’s so charming and wryly amusing that we (and Goloborodko) can’t help liking him. The pair become politicians-on-the-incognito-run in Season Two, to great comedic effect. Yevhen Koshovyy is an improbably (and somewhat one-dimensionally) clownish oaf at first as the most undiplomatic freshly-minted foreign affairs minster Serhiy Mukhin, but he grows more able and sympathetic thanks to the proddings of his exasperated, but hyper-capable and ever-so-serious, assistant Oksana (appealingly played by Olha Zhukovtsova-Kyiashko). Koshovyy earned his award nomination in a frenetic series of banquet scenes in the film. His thankless job is to stall a visiting delegation from the IMF. His solution is to ply them with drink: every time he claps his hands, entertainers in ethnic garb sing with gusto, and the guests’ cups are refilled. It is wonderfully funny.

The ensemble also has Olena Kravets as Olha Mishchenko, the ex-wife for whom Goloborodko clearly still carries a torch. We kept expecting a romantic reconciliation between the two, but it is a story thread that is not pursued. Mykhailo Fatalov plays Mikhail Tasunyan, the capable Armenian head of the Ukrainian security service. Viktor Saraykin plays Petro Goloborodko, the new president’s bumptious father. The role of the femme fatale Anna is shared between Halyna Bezruk (in Season One) and Anastasia Chepelyuk in (Season Two). Kateryna Kisten plays Svetlana Sakhno: as Goloborodko’s opinionated sister, you never need to ask her twice what she really thinks. Dmitry Surzhikov is unsettlingly realistic as the very capable and very treacherous Dmitry Surikov, who rises through the ranks to become the all-too-believable (and not at all funny) false ally, chief villain, and eventual usurper of the government. It is a flawless portrayal, yet his presence is somewhat jarring — he’s more a figure from dark political drama than satire or comedy. And his abrupt self-destruction feels contrived and unconvincing in such a ruthless and effective antagonist. George Povolotsky is amusing as Tolya, the president’s unflappable, mostly mute, bodyguard. But a few promising characters are underutilized: Goloborodko’s highly efficient, no-nonsense secretary Bella (Valentyna Ishchenko) disappears after the first season. So, inexplicably, do his appealing mother and niece (played by Nataliya Sumska and Anna Koshmal, respectively): their sudden absence makes no sense, storywise. For her part, Tetyana Pechonkina plays the new president’s tough-as-nails former schoolmarm Nina Tretyak, whom he selects to run the country’s wayward security service. But, she is gone after only a couple of episodes when her lieutenants spike her drink with a hallucinogenic drug to discredit her.

Volodymyr Zelenskyy in “Servant of the People” — courtesy of Kvartal 95 and Vision TV.

The series makes very effective use of music, starting with its instantly engaging title theme. To gentle visuals of its eponymous servant of the people riding his bicycle through Kiev, we get a gentle ballad, with human vocals doing the saxophone parts, all with wry lyrics: “I love my county, and I even love my wife. And, I love my dog, too…. And [I] fight some Superman… only use knives when I have to. The whole yard knows and I’m sure it shows: I’m a Servant of the People.” Another piece, full of energy and changes in mood, featuring what sounds like piano and brass band, combines an oom-pa-pa sound with a three-note infusion of drama; it sometimes is heard in the midst of an episode and occasionally over the end credits. A third piece is a male and female vocal duet with an addictive sound that could be straight out of a Eurovision music competition.

Last, but not least, musically, there is sweeping orchestral inspiration in the last minutes of the series. In that scene, the line between the fictional Goloborodko and the real-life Zelenskyy portraying him blurs. One or both of them exhort listeners to fight the good fight, noting that ‘Even if we fail, at least we tried.’ What powerful resonance that has now, in 2022, when Ukraine is victim of a criminal war of aggression by Putin’s Russia. Was the final season of “Servant of the People” and that final figurative call to moral arms a conscious opening move in the transition from television fiction to real life politics? Whether by chance or design, the television series became a springboard for its star and its political values, propelling them into the real world: In March 2018, a political party named after the television series was born; one year later, Zelenskyy was actually elected President of Ukraine. The rest, as they say, is history.

Copyright © 2022 by John Arkelian.

John Arkelian is a lawyer, journalist, and foreign policy analyst.

Editor’s Note: Canada’s Vision-TV aired all three season of “Servant of the People,” as well its movie spin-off, starting in April 2022. A repeat broadcast began in early June 2022, with six different episodes per week airing Tuesdays through Thursdays at 10 and 10:30 pm. The program is in Ukrainian with English subtitles. https://www.visiontv.ca/shows/servant-of-the-people/

To read about the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, visit: https://artsforum.ca/ideas/the-wide-world

******************************************

*************************

Witnessing the Birth of a Family

© By John Arkelian

Family… Connections… At the heart of those ideas is our sense of self-identity, our very state of being: For we are in some ways

A family reunited in “Birth of a Family” (courtesy of CBC).

defined by those to whom we are most closely connected. And, for most of us, what closer connections do we have than those that bind us for life to our family? Our family is the well-spring of our roots, our history, and very often our fundamental character, as well as the first and most enduring expression of our God-given mission to love our fellow mortals. But what if you have been sundered from your family, unaware that you even have siblings? That’s the subject of the new NFB documentary “Birth of a Family,” which was broadcast in abbreviated form on CBC in November 2017.

The film follows a few days in the lives of Betty Ann, Esther, Rosalie, and Ben, who were taken from their Dene mother as babies (or, in one case, as a very young child) as part of Canada’s “Sixties Scoop,” that took an estimated 20,000 indigenous children and placed them with white families. In this case, they were dispersed across multiple provinces and two countries: “We were never given a choice. We were never asked, ‘Do you want to be separated?’” They are middle-aged now, and they’ve had good lives with their adoptive families: “I was raised in a good and decent home. And I’ve had many people say to me, ‘Well, you were lucky.’” At one time, that proposition might have elicited agreement from the adoptees themselves. But there was also a gnawing sense of something missing: “I always imagined that if I met my real family that I’d get something that I didn’t have.”

50 years after they were parted, the siblings meet for the first time at Banff National Park. The overwhelming beauty of that place is an apt setting for the powerful emotions they experience. There are long talks, shared tears, group hugs, sharing of childhood photos, and a birthday cake to make up for the “211 birthdays we’ve missed.” A visit to a First Nations’ interpretative center leaves one of them in tears, suddenly aware of her lost cultural roots. Discussing their late mother, the siblings note that she had been wrenched away from her family and sent to a residential school. She never returned to a native community after that. Was it because she’d been inculcated with a feeling of being ‘inferior’ to whites, or was she resentful at her community for allowing her to be taken away? One issue that is never addressed is the reason for the siblings being removed from their mother in the first place. Yes, it was part of a culturally-biased program, implicitly (and presumptuously) designed to purge them of their ‘nativeness;’ but, was their mother deemed to be unfit to care for them? And, if so, was such an apprehension about her fitness justified?

The quietly affecting bonding between these reunited siblings makes us feel a warm connection to them. Their story is not one of recriminations and bitterness. There is sadness here for what was lost but also joy at what had been rediscovered: “It’s not a ‘reunion,’ it’s a family union.” And that’s an irresistibly heartwarming story.

Note: “Birth of a Family” can be seen at http://www.cbc.ca/cbcdocspov/episodes/birth-of-a-family

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

******************************************

Our Revels Now Are Ended: In Memory of Jonathan Frid

© By John Arkelian

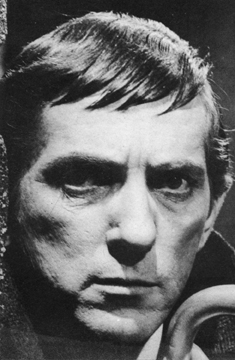

Jonathan Frid commanding the stage (courtesy of J. Frid).

“Our revels now are ended. These our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits and are melted into air, into thin air: And, like the baseless fabric of this vision, the cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples, the great globe itself, yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve, and, like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.”

William Shakespeare, from “The Tempest” Act 4, Scene 1

I was fortunate to call Jonathan Frid, the eminent Canadian actor who was this country’s answer to Richard Burton, my friend. Trained as an actor at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts in London, England, John earned a Master’s in Directing at Yale, and he went on to work in Shakespearian theater in Toronto (before the establishment of Stratford Festival) and in the early days of CBC Radio drama (an invaluable national treasure that government cutbacks to the CBC have recently killed). But he spent most of his career in the United States, working on and off Broadway with such luminaries as Katherine Hepburn and John Houseman. In 1967, he was hired to play a vampire, Barnabas Collins, on the ABC-TV Gothic drama series “Dark Shadows.” He invested that fantastical creature with deep humanity and dignity. A series that was on the verge of cancellation suddenly attracted stratospheric ratings; and John’s riveting, charismatic, and nuanced portrayal of a tragic and tormented man who was afflicted with deep inner sadness and dark turmoil of truly Shakespearian proportions made him a superstar and a lasting icon of popular culture in the United States. Ironically, “Dark Shadows” was hardly shown in Canada, and John remained almost unknown here in his native land. Three film roles (two of them as the lead) and a return to his beloved work as a stage actor followed, as did a touring one-man show (that twice came to our immediate environs)

Jonathan Frid as Barnabas Collins: The vampire as hero (courtesy of J. Frid)

in which John remarkably transformed himself — using only his voice, face, and body language — into characters as diverse as Richard the Third, Caliban, and the deadly antagonists from Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” to cite only a few examples. I met John when he retired back to Canada: I conducted a series of extensive interviews with him (interviews which ran to about twelve hours in length!), and we became fast friends. I fondly remember a remarkably gifted performing artist, a man who was unpretentious about the great fame he continued to have in other countries, an iconoclast with a wry sense of humor, a man who was as calmly unperturbed about aging as he was about his unaccustomed anonymity, and an elegant man of great courtesy, generosity, and talent. John died on April 14, 2012. Those who knew him, and those who were touched by his work, will miss him.

© 2012 by John Arkelian.

You haven’t heard the passage from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest” which is quoted above, until you’ve heard Jonathan Frid recite those words — with inimitable authority, mystery, and poignancy.

Editor’s Note: Jonathan Frid has always been overlooked for such recognition as the “Canadian Film and Television Hall of Fame” and “Canada’s Walk of Fame,” even though he is an obvious, essential choice for both. Artsforum nominated John Frid for both awards several years ago and did so again in early April 2012. Is it too much to hope that he might get the recognition posthumously that he deserved to get in life? (Frid has also always been inexcusably overlooked for the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards.)

****************************************************************

“Stargate Universe” Consigned to the Black Hole of Unwarranted Cancellation!

It defies belief that a series as engrossing, well-written, and well-acted as

“Stargate Universe” (courtesy of MGM)

“Stargate Universe” would get an unceremonious heave-ho after a mere two seasons. Why not approach other potential broadcasters, such as Canada’s

CBC or Space networks, in an effort to find a new home for this first-rate

“Stargate Universe” (courtesy of MGM)

series? SGU is the best science fiction series on television right now, and one of the very best in that genre to appear in years. It also happens to make very

compelling viewing as character-drama, quite apart from its genre setting and subject matter. As the production home of all three Stargate television series, Canadians should be proud of their country’s contribution to Stargate Universe’s quality and the loyalty it commands among its viewers.

John Arkelian

May 30, 2011