Neglected Gem: “The Whole Wide World”

© Reviewed by Steve Vineberg

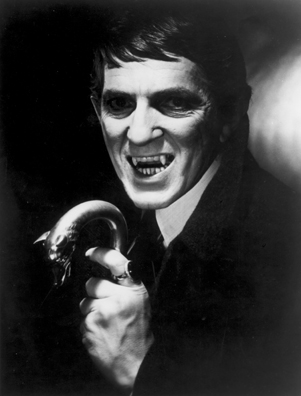

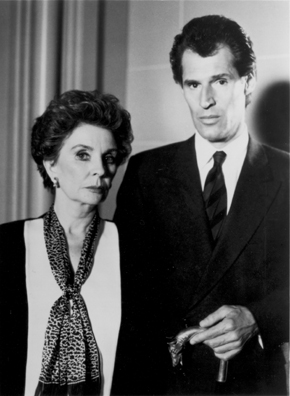

As Bob Howard, the pulp writer who romances a small-town schoolteacher in 1930’s West Texas in “The Whole Wide World” (1996), Vincent D’Onofrio gives the best performance of his career. D’Onofrio uses his thick, squarish pugilist’s looks; a walrus mustache he tries out, or an outsize Mexican hat, which sits on his face with unexpected ease – absurd appendages you suddenly realize complete him. He gives Howard a physicality that’s both lumbering and exploratory: tracking through the cornfields or down a country road, he always seems to be stretching toward something, a world only he can see. That’s the heart of Bob Howard, the man who created Conan the Barbarian: he lies such a fervent life in his head, rehearsing his stories in the fields or chanting them like fearful verse, bent over his typewriter, that he disappears into it. Conan is Bob’s romantic version of himself, part monster, part seducer. When his ailing mother (Ann Wedgeworth) interrupts him to call him to the phone, she has to shout to be heard above the din of his imagination. For this bold, possessed man, who brawls against the world every time he marks out a new tale, and whose braggadocio and non-conformity mask deep-flowing misanthropy and despair, D’Onofrio seems to invent his own style – a kind of homegrown pulp-theatrical machismo. It’s as if he’d crossed the stylized all-American forthrightness of John Wayne with the romantic sweep and tormented soul credited to nineteenth-century actors like Edmund Kean and Edwin Booth.

“The Whole Wide World” is the work of the screenwriter Michael Scott Myers and the director Dan Ireland, and it’s enchanting. Modest and resolutely offbeat but lovingly crafted (the soft-edged cinematography is by Claudio Rocha), it’s a truly original piece of filmmaking, and it deserved to be the kind of small picture the audiences sometimes fall in love with. But it passed by pretty much unnoticed. Even the usually programmatic composer, Hans Zimmer, seems to have been caught up in the movie’s spell: he wrote an evocative and often witty score that suggests, in its small way, the kind of experimentation Aaron Copland went for in his soundtracks.

Renée Zellweger plays Novalyne Price, the young teacher and hopeful short-story writer who becomes enamored of Bob and tries to draw him out of his isolation. Their courtship has a comic intensity brought on by her determination and his tendency to back off unexpectedly and then, just as suddenly, come charging at her like an offended bull. Zellweger plays Novalyne with a mixture of curiosity and raucousness that reminded me of Emily Lloyd in “Wish You Were Here,” but her fiery Texas style – she never evades a fight – has a soft, silky underlayer. These two are remarkable together. Wedgeworth, as the protective, dying mother who claims Bob’s first loyalty, adds a third superb performance. Wedgeworth’s Mrs. Howard is the kind of fading southern woman Tennessee Williams might have conceived: the sensuous aroma of gardenia drifts off her, mixed in with the odors of decay. And Bob’s connection to her is crypto-Oedipal.

“The Whole Wide World” is a biopic, but mostly it’s the story of a failed romance. Bob tells Novalyne that west Texas is dangerous; he sees the land as infested with the perils he puts into his stories. In his mind, the civilization he lives in is nothing but a blind: “Man gets more depraved and demonic all the time” and “Maggots and corruption are all around you.” But she’s a believer in civilization, in hospitals and schools. For all her feistiness, her mild cursing, she’s a deeply conventional woman, and their relationship is like the classic one found in many westerns between the cowboy and the schoolmarm. Robert Warshow wrote, in his great essay “Movie Chronicle: The Westerner:”

The Western hero… resembles the gangster in being lonely and to some degree melancholy… his loneliness is organic, not imposed on him by his situation but belonging to him intimately and testifying to his completeness… The Westerner is not… compelled to seek love; he is prepared to accept it, perhaps, but he never asks more of it than it can give; and we see him constantly in situations where love is at best an irrelevance. If there is a woman he loves, she is usually unable to understand his motives; she is against killing and being killed, and he finds it impossible to explain to her that there is no point in being “against” these things: they belong to his world.

“The Whole Wide World” does something very unusual: it recycles the old tension between the westerner and the eastern woman (who is often a schoolteacher) but in a modern western setting (and with a western heroine), where the land has been thoroughly civilized and only a man like Bob Howard, who is neurotically solitary and somehow profoundly displaced, can continue to believe in the frontier. The film’s idea is that his vision of the world as a still primitive and dangerous place, where adventure lurks around every corner, is what enables him to write the vigorous pulp stories he writes.

Bob’s writing consumes his entire life, and when it doesn’t – when his mother’s condition distracts him – he can’t write at all. Yet it’s Mrs. Howard’s indulgence of her son, their strange intimacy, that allows his imagination to roam free. She has kept him, essentially, a child. And she interposes herself between him and Novalyne, whom she sees as an outsider she has to protect him (and, presumably, his writing) from, or as competition, or both. When Novalyne sees them out together in a store, Mrs. Howard lords it over her silently, throwing her haughty looks from across the floor, one-upping her; in a later scene she waves to Novalyne smugly from her porch swing, as if dismissing her. But his complexity can’t be explained only by her influence. When he and Novalyne quarrel over the phone over his refusal to take her to a Christmas party, he slams down the phone and goes out to take a drive, and he’s so eruptive that he floods the car and cries out, “Mama, the car won’t start!” in a faded, hysterical voice, and takes a sword, of all things, out in the field to vent his anger and hurt. He winds up crying brokenly to his mother. The most uncharitable way to describe this response would be to call it a child’s temper tantrum, but the anguish is very real and goes very deep. And then his world, so fragile to begin with, falls apart when his mother approaches death. He shoots himself after he learns that she won’t recover, leaving behind a poem in his typewriter: “All fled, all done, / So lift me on the pyre / The feast is over / The lamps expire.” It’s really a eulogy for himself.

Harve Presnell plays the underwritten role of Bob’s father; the confidence he shares with Novalyne is one of the two scenes in the movie that doesn’t quite work, though Presnell is very fine in it. (The other is the coda, which feels extraneous.) Otherwise, Ireland and Myers sustain their unconventional period romance; the film is a triumph of sensibility and generosity of imagination. The title derives from the phrase a mutual friend uses when he introduces Bob to Novalyne and calls him “the best pulp writer in the whole wide world.” But as the film goes on, you realize that it mostly refers to the world of his fiction, which encompasses him, and the world that Novalyne is on the brink of entering – the world that graduation from college, a teaching career, graduate school in Louisiana, and her love for Bob present to her. Myers adapted his script from “One Who Walks Alone,” the memoir Novalyne wrote, as Novalyne Price Ellis, at the age of seventy-six; the title is more touching when you consider that she waited her whole life to write down this story, as if she had to approach the end of her world before she could finally understand what had happened to her in her youth, and what it meant to her. This movie has the magical effect of stretching itself around you as you watch. For two hours, the complicated love affair of an adventure story writer and a schoolteacher becomes, for us, the whole wide world.

Steve Vineberg is Distinguished Professor of the Arts and Humanities at College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he teaches theatre and film. He also writes for The Threepenny Review and is the author of three books: “Method Actors: Three Generations of an American Acting Style,” “No Surprises, Please: Movies in the Reagan Decade,” and “High Comedy in American Movies.” Steve Vineberg was born and raised in Montreal.

Copyright © 2022 by Steve Vineberg.

Editor’s Note: The foregoing review originally appeared in Critics at Large and appears here with the permission of its author. Visit Critics at Large at: https://www.criticsatlarge.ca

*************************************

2019’s Top Ten Times Two

Two film critics, two different takes on the year’s top films:

The Year’s Best Films by Milan Paurich

(1) “Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood”

(2) “1917”

(3) “The Irishman”

(4) “Waves”

(5) “Synonyms”

(6) “Parasite”

(7) “Marriage Story”

(8) “Little Women”

(9) “A Hidden Life”

(10) “Richard Jewell”

Runners-up (in alphabetical order): “Ad Astra,” “An Elephant Sitting Still,” “The Art of Self Defense,” “Ash is Purest White,” “Atlantics,” “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,” “Birds of Passage,” “Blinded by the Light,” “Booksmart,” “By the Grace of God,” “Charlie Says,” “Climax,” “Dark Waters,” “Everybody Knows,” “The Eyes of Orson Welles,” “Gloria Bell,” “Her Smell,” “High Life,” “The Image Book,” “The King,” “The Last Black Man in San Francisco,” “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” “Midsommar,” “Never Look Away,” “The Nightingale,” “Non Fiction,” “Pain and Glory,” “Peterloo,” “Portrait of a Lady on Fire,” “Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story,” “Shadow,” “6 Underground,” “63 Up,” “The Souvenir,” “Toy Story 4,” “Transit,” “Uncut Gems,” “Under the Silver Lake,” “Us,” and “The Wild Pear Tree.”

Milan Paurich is a film critic based in the United States.

© 2020 by Milan Paurich.

*********************

The Year’s Best Films by John Arkelian

The following films are reviewed at: https://artsforum.ca/film/at-theaters/at-theaters-3-0

(1) “All is True”

(2) “Jojo Rabbit”

(3) “1917”

(4) “Stan & Ollie”

(5) “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood”

(6) “Parasite”

(7) “The Peanut Butter Falcon”

(8) “Joker”

(9) “Judy”

(10) “Hotel Mumbai”

Runners-Up (in approximate order of preference): “Richard Jewell,” “The Farewell,” “Little Women,” “Yesterday,” “Once Upon A Time in Hollywood,” “The Grizzlies,” “Gloria Bell,” “The Upside,” “The Art of Racing in the Rain,” “Toy Story 4,” “Arctic,” “Just Mercy,” “Fighting with My Family,” “Brittany Runs a Marathon,” “The Extraordinary Journey of the Fakir,” “Downton Abbey,” “Destroyer,” “Ad Astra,” “After the Wedding,” “The Lighthouse,” “How to Train Your Dragon 3,” “Frozen 2,” “Luce,” “Blinded by the Light,” “The Goldfinch,” “The Good Liar,” “The Secret Life of Pets 2,” “Hustlers,” “Waves,” “Harriet,” “Doctor Sleep,” “Zeroville,” “The Mustang,” “Late Night,” “Where You’d Go, Bernadette?,” “The Hummingbird Project,” “Us,” “Cats,” “Bombshell,” “Tolkien,” and “Dark Waters.”

Films That Got Away: “A Hidden Life,” “Pain and Glory,” “Booksmart,” “Vita & Virginia,” “Official Secrets,” “Maiden” “Marriage Story,” et al.

John Arkelian is founding editor of Artsforum Magazine

© 2020 by John Arkelian.

*************************************

“Yesterday”

© Reviewed by Julia Rath

“Yesterday” (U.K./USA, 2019) is an uplifting movie that can be

Himesh Patel & Lily James in “Yesterday” (photo by Jonathan Prime) — courtesy of Universal Pictures.

appreciated on so many levels. The story is about Jack Malik, a struggling musician (played lovingly by Himesh Patel) who is cast into an alternate universe where The Beatles don’t exist, and he winds up reinventing and performing their songs as his own. Throughout the film, he sees himself as a fraud and wonders if he’ll ever be caught – and that makes him extremely uncomfortable. But as time goes on, he becomes less uneasy about the path he has taken. Now he’s become a famous rock star with some of the most memorable and classic songs ever created in his repertoire. How many people could only dream of such a fabulous life? How cool is that?

Even with his extraordinary talent, he could not catch a break at the

Lily James & Himesh Patel in “Yesterday” (photo by Jonathan Prime) — courtesy of Universal Pictures.

very beginning of his career. Most people ignored him (even his parents) or wanted to change who or what he was. Only his manager Ellie Appleton (Lily James) had complete faith in his abilities from the very moment she saw him on stage fifteen years earlier. Her abiding affection for him went above and beyond recognizing his songwriting abilities or enjoying his lovely voice and his guitar and piano-playing skills. Rather, she saw him as a total person – which, like his music, towered well above all the various and sundry parts that made up the whole.

Miracles do happen: Jack’s life changes and life changes him – but not necessarily for the better. He wants his old life back. He initially pines for yesterday: “All my troubles were so far away.” But once Jack realizes that he can make a future for himself and that his greatest gift is giving away the songs that he had not actually

Himesh Patel & Lily James in “Yesterday” (photo by Jonathan Prime) — courtesy of Universal Pictures.

written, only then does he love unconditionally, and he is set free. Life is no longer about the exploitative present or about a past that really wasn’t so wonderful after all. It is now about writing his own future and living the life he is supposed to live.

But beyond the storyline itself and the sheer joy of hearing The Beatles’ music, the movie brings to the fore a number of ponderable questions:

(1) How many people are equally talented as those who are famous (like The Beatles) and have never been heard of? How many such people remain undiscovered? Jack was one of these talented geniuses who kept marching in place until luck or fate intervened. But in his case, it wasn’t being at the right place at the right time, but rather being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Life is serendipitous and unpredictable.

(2) Then there is the issue of promotion and self-promotion. How much of that is necessary or useful to a successful career? Obviously, there was some need for Jack to have a manager, whether it was Ellie or the cut-throat Debra (Kate McKinnon). What was most important, however, was having the courage of his convictions. For example, Jack had the foreknowledge that his songwriting talent was really great (of course, since The Beatles’ songs were so magnificent); and with this faith, he could draw on his self-confidence and state unequivocally, “Hey, this is amazingly good; listen to me!” Standing up for the brilliance of his creation was key in getting himself recognized.

(3) How much does success have to do with the amount of native talent a person has to begin with? Jack had the ability to deconstruct and reconstruct all the various tracks of the Beatles’ songs. The average person perhaps might be able to sing or play these songs, or simply enjoy them in their complete form. But Jack had a complex understanding not just of the lyrics and music but also their arrangement and instrumentation. He even went off to Liverpool to understand The Beatles’ inspiration. In so doing, he still felt like a phony by borrowing somebody else’s body of work – and getting credit for it (and tons of money to boot). Yet everybody in his alternate universe thought he was crazy when he tried to give the credit away to somebody else, to a musical group that they had never heard of.

(4) This finally begs the deepest question of them all: the origins of the creative process. What does it mean to be creative? Where does imagination come from? Where does one get the inspiration for doing something new, exciting, or different that nobody has ever seen before or since?

I had a good friend, who died about three years ago, who used to tell me that he could see little people (leprechauns) that nobody else could see. They would sing and dance around him and tell him jokes and stories. He would listen to them and imitate them. He would tell me that these little creatures were his inspiration for most of his creativity. (The other factor was “being in the zone” and letting God, or the Higher Power, handle the rest.) Though I never thought my friend was making any of this stuff up, I always thought that his story was really, really weird. Why he would confess to me and nobody else was always a mystery. (And, no, it was not because he thought I was gullible.) After seeing “Yesterday,” perhaps my friend’s perspective on the creative process might have been strange but not impossible. He too had had an event that had altered his life –in his case, a motorcycle accident, rather than a bicycle accident, as in the movie. Maybe when people confront death head-on and live through the experience their lives change in ways that we will never fully comprehend. Now I need to consider why all of these odd premises initially sound so far-fetched; but, today, maybe not so much.

Julia Rath is a freelance writer in Chicago.

Copyright © 2019 by Julia Rath.

**************************************

Top Ten Times Two — 2018

Two film critics, two wildly disparate top ten lists, with scarcely a film in common. There may be objective indicia by which a film’s quality can be weighed; but, when you get right down to it, there’s a big subjective element in how any of us react to the movies. JA

The Year’s Best Films by Milan Paurich

(1) A tie: “The Other Side of the Wind” (Orson Welles) & “Roma” (Alfonso Cuaron)

Two miracle movies that (surprise!) have Netflix to thank for their very existence. “Roma” begins in 1970, the same year Orson Welles commenced production on “The Other Side of the Wind,” his legendarily uncompleted final film. Both are validations of auteurist cinema as a veritable force of nature. Both are in iridescent B&W. Both are masterpieces. In a perfect world, “The Other Side of the Wind” would have been released in 1972 since it feels like the missing link between Dennis Hopper’s “The Last Movie” (finally released on Blu-Ray this year) and Bernardo Bertolucci’s “Last Tango in Paris.” “Roma” is a Cuaron labor of love: his best, most personal film since 2001’s “Y Tu Mama Tambien” (still one of the new millennium’s greatest movies).

(2) “Vice” (Adam McKay)

Before directing 2015’s “The Big Short,” Adam McKay was primarily known as the director of the best Will Ferrell comedies (“Step Brothers,” “Talladega Nights,” etc.). Now he’s America’s Armando Iannucci: one of our finest and most fearless filmmakers, someone who speaks truth to power without ever losing his sense of humor or bilious outrage. Only McKay could make a biopic about G.W. Bush’s veep Dick Cheney that’s as rambunctiously entertaining as it is infuriating. Featuring one of the year’s finest ensemble casts, too, including a career-best Christian Bale performance as Cheney that’s downright (and hilariously) uncanny.

(3) “Isle of Dogs” (Wes Anderson)

Anderson’s latest stop-motion animated treasure is brilliantly imaginative, visually resplendent, wryly amusing and exquisitely moving without an ounce of Disney treacle. Set in a future version of Japan in which the entire dog population has been relocated to an island waste dump by a cat-loving despot, the film has more heart, wit and, yes, soul than a dozen live-action movies. The vocal casting is wonderful, too: Bill Murray, Bryan Cranston, Scarlett Johansson, Harvey Keitel, Yoko Ono (yes, Yoko Ono!), Jeff Goldblum, etc. It’s another instant classic by Anderson, my favorite contemporary American filmmaker. Puts this year’s combined Disney and Pixar output (both sequels; yawn) to shame.

(4) A tie: “Lean on Pete” (Andrew Haigh) & “The Rider” (Chloe Zhao)

Haigh’s first American-lensed film was a boy and his horse story that was also a masterpiece of empathy. After an orphaned 15-year-old (Charlie Plummer, remarkable) rescues the titular ailing racehorse, they embark upon a cross-country journey to reunite with the boy’s estranged aunt (his only living relative). Beautifully lensed and impeccably acted (Steve Buscemi, Chloe Sevigny, Steve Zahn, Travis Fimmel and Amy Seimetz all make indelible impressions), it’s a movie to treasure. The tears it earns are both cathartic and joyful.

“The Rider” is an extraordinary film about a young Native American bronco rider (Brady Jandreau) whose promising rodeo career is cut short by a near fatal head injury. Like Zhao’s previous neorealist marvel, “Songs My Brothers Taught Me,” the cast is comprised of non-pros essentially playing fictionalized versions of themselves. It’s a risky gambit that doesn’t always work (see Clint Eastwood’s clunky “The 15:17 to Paris”), but does so beautifully here. It’s as visually resplendent as your average Terrence Malick movie – and just as besotted with nature and a kind of secular spiritualism – but with more narrative meat on its bones. A humanist triumph that deserved to be seen by the widest possible audience.

(5) “BlacKkKlansman” (Spike Lee)

Black lives have always mattered, and black films (among them “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “Widows,” “Sorry to Bother You” and “Blindspotting”) seemed to matter more than ever in 2018. None more so than Spike Lee’s wildly kinetic Cannes Golden Palm winner which was the “Do the Right Thing” auteur’s most audience-friendly joint since 2006’s “Inside Man.”

(6) A tie: “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” (Marielle Heller) & “Private Life” (Tamara Jenkins)

Two quintessentially New York stories populated with edgy, abrasive ‘difficult’ protagonists, memorably played by (among others) Melissa McCarthy, Richard E. Grant, Paul Giamatti and Kathryn Hahn. Both directed (thank you!) by women.

(7) A tie: “First Man” (Damien Chazelle) & “Wildlife” (Paul Dano)

1960’s America: Lives of quiet desperation, and lonelier than the moon. (Hint: only one of them features Apollo astronauts.)

(8) “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” (Joel and Ethan Coen)

The Coen Brothers’ omnibus western rightfully belongs in their already crowded canon of masterpieces: critics who complained that it was a minor-tier work clearly never understood (or truly loved) their films in the first place.

(9) “Burning” (Lee Chang-Dong)

A South Korean “L’Avventura” with youthful anomie replacing Antonioni’s middle-aged malaise.

(10) “Minding the Gap” (Bing Liu)

In a year of first-rate documentaries , this was my favorite. Yes, it follows the “Hoop Dreams” template just like countless other docs from the past 24 years. But a case could be made (hey, I just did!) that it’s even better than Steve James’ groundbreaker.

Runners-up (in alphabetical order): “Annihilation,” “At Eternity’s Gate,” “Capernaum,” “Cold War,” “The Death of Stalin,” “Destroyer,” “Double Lover,” “Eighth Grade,” “The Favourite,” “First Reformed,” “Green Book,” The Guardians,” “Hal,” “Happy as Lazzaro,” “The House That Jack Built,” “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “Ismael’s Ghosts,” “Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc,” “The King,” “The Land of Steady Habits,” “Let the Sunshine In,” “Mission Impossible: Fallout,” “Monrovia, Indiana,” “The Mule,” “Never Goin’ Back,” “Science Fair,” “Suspiria,” “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead,” “Widows,” “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” “You Were Never Really Here,” & “Zama.”

Milan Paurich is a film critic based in the United States.

© 2019 by Milan Paurich.

**********************

The Year’s Best Films by John Arkelian

The following films are reviewed at: https://artsforum.ca/film/at-theaters/at-theaters-3-0

(1) “A Quiet Place”

(2) “Green Book”

(3) “First Reformed”

(4) “Leave No Trace”

(5) “BlackKklansman”

(6) “Bohemian Rhapsody”

(7) “Thoroughbreds”

(8) “The Favourite”

(9) “Hostiles”

(10) “Eighth Grade”

Runners-Up (in random order): “A Simple Favor,” “Mary Queen of Scots,” “The Mule,” “The Sisters Brothers,” “Bad Times at the El Royale,” “Colette,” “On the Basis of Sex,” “The Death of Stalin,” “If Beale Street Could Talk,” “At Eternity’s Gate,” “Sicario: Day of the Soldato,” “Vice,” & “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.”

John Arkelian is founding editor of Artsforum Magazine.

© 2019 by John Arkelian.

**************************************

Intimations of Grace at the Movies

© By John Arkelian

The idea of grace is connected with the God-given gifts of virtue and redemption – worthy subjects, both, for the person of faith to contemplate. But, seeking intimations of grace at the movies can be a hit-and-miss affair. Films which overtly address religious faith typically have a proselytizing agenda, and their preoccupation with preaching usually gets in the way of good story-telling, overwhelming such basics as plot and character development with heavy-handed didacticism. Four recent movies touch on aspects of grace: three of them are explicitly Christian in perspective while the fourth is merely implicitly grounded in faith. While three of the four are not particularly good movies, each manages to have something useful to say about grace.

The best of the quartette is “Paul, Apostle of Christ.” It’s the year 67 AD, and the apostle Paul (James Faulkner) is imprisoned in Rome, awaiting death, while the Christian community there is facing brutally lethal persecution. They have recently become convenient scapegoats, falsely accused of setting the fires that destroyed part of the city. Into this fraught, perilous setting comes the apostle Luke (Jim Caviezel, who played the title figure in 2004’s violent “The Passion of the Christ”); he ministers to the beleaguered flock and visits Paul in prison to lend comfort to his mentor and friend while he secretly records his story for posterity. Paul has unshakeable faith, and he is adamant about not responding to violence and hate with more of the same: “Where sin abounds, grace abounds more.” His strength and Luke’s gentleness are admirable without feeling artificial. The leads are ably supported by Olivier Martinez, Joanne Whalley, and John Lynch – as, respectively, the severe military officer in command of the prison who has an unexpected capacity for decency, and two devoted leaders of the faithful. Solid performances, and a message that feels unforced (“You are completely known to God, and you are completely loved”), combine to pleasing result.

In “God’s not Dead: A Light in Darkness.” a historic church situated on a now secular university campus is no longer welcome there. Its pastor (David A.R. White) fights the attempt at expropriation. Ill-feelings and mutual escalation ensue (an act of impulsive vandalism even causes an accidental death). The pastor is jailed for contempt of court for refusing to hand over transcripts of his sermons, though, oddly, what is so controversial about their contents is never revealed. The result is artificial (real people don’t talk like this), heavy-handed, and didactic. It’s inculcated with the notion that organized religion is under attack by secular foes; but, so far, in the West at least, that’s a hyperbolic premise. There’s a message here about forgiveness, humility, and healing (Psalm 30:5 is cited: “Weeping may last through the night, but joy comes in the morning”), but the film is slow to reach those self-evident conclusions. The writing and cast are uneven (and occasionally shaky), with the standout among the latter unexpectedly provided by a character who has lost his faith and is untroubled about that fact (the engaging John Corbett as the preacher’s older brother and legal white knight).

“I Can Only Imagine” is based on the true story of the lead singer for “MercyMe,” a Christian music band that struck a chord with the song that gives the film its title. It’s well-intentioned stuff – about turning pain to inspiration. But its protagonist (J. Michael Finley’s Bart Millard) is dull. The story gets much more emotional traction from three others: Dennis Quaid, as his physically abusive father; Trace Adkins, as his gruff agent (“Son, the sheer volume of words that comes out of your mouth is exhausting”); and Nicole DuPort, as the Christian singer Amy Grant.

The new film adaptation of “A Wrinkle in Time,” which sends three children on a trans-dimensional journey to find the missing father of two of them, is a disappointment. Its source material, the 1962 novel by Madeleine L’Engle (her Christian faith was more implicit than overt in this book) is a wonderful classic about love, family, courage, and self-acceptance. And its director, Ava DuVernay, did first-rate work with 2014’s “Selma.” But authenticity is missing here, in a film hampered by an uneven cast (the actors playing the young siblings are awkward), an over-reliance on computer-generated effects (and on overly ostentatious make-up and costumes), and a misreading of the story as an action piece, when it is actually anchored in relationships – the bonds that tie family and friends together through thick and thin. The casting issues extend to the trio of eccentric ladies (they are angels, though that term is not used): Oprah Winfrey is too immediately identifiable as a celebrity (and inexplicably magnified here to towering height) for us to accept her in this role. Something magical becomes something trite and dull here. The screenplay errs by inflating the potency of evil: “The only thing faster than light is the darkness.” And the heart of the novel, which is about intimations of grace, is neglected: “What if we are here for a reason? What if we are part of something truly divine?”

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

**************************************

Reclining Your Way to an Impaired Movie-Going Experience

© By John Arkelian

Out with the old, in with the new? That seems to be the premise

Ready to recline at Landmark Cinemas.

behind the replacement of traditional cinema chairs at Landmark Cinemas in Whitby, Ontario. That multiplex has long been the best cinema in the Eastern Greater Toronto Area, under its changing owners (first AMC, then Empire Theaters, and most recently Landmark). The new seats, which are being installed in all 24 auditoriums over the course of several months certainly look good. They are huge, black imitation-leather behemoths, capable of reclining to a nearly horizontal position. But the fact that they are so much bigger than the traditional tried-and-true padded cinema seats they are replacing has created a host of unforeseen problems. Each row of the new oversized chairs seems to take up as much space as two rows of their predecessors. To accommodate their girth, a new flooring superstructure (or ‘platform’) has been erected on top of the old one. Instead of the floor base being solid concrete, as it used to be, it is now a suspended (plywood?) platform, creating a drum-like effect when it comes to vibration. Every lumbering footfall of movie-goers clomping their way up and down the stairs now vibrates freely (and noisily) down the entire length of each row. (Even the sound coming from the speakers is now enough to set the new suspended flooring to vibrating.) The floor literally shakes, something its solid concrete precursor could never do. The resulting ‘vibrate-atron’ (a term we just coined) may “transform your movie-going experience,” as Landmark’s ads proclaim – but not in a good way.

But that’s not the only adverse consequence. The new suspended platform superstructure that supports the big new chairs and much wider new rows is substantially higher off the ground than the solid concrete footing that it now covers. Everything is at a higher ‘altitude,’ and that has created a new problem. Every time people stand up in the back couple of rows (whether arriving late or on incessant errands to the lobby), they block a large part of the projected picture on the screen. The new suspended floor is much higher now; so, people standing on it block the projector. The black silhouettes of human figures that now intrude on the screen aren’t just the top of heads – they are the whole torso, from waist up!

In addition, the back few rows in each auditorium have been outfitted with an extra section of platform to raise them even higher off the main platform. The trouble is: in those rows, the feet of even a very tall man dangle inches off the ground if the seat is left in the upright position, an ergonomically uncomfortable oversight that forces people in those rows to recline – whether they want to or not. Further, the stairs in the auditoriums aren’t just noisy – they are also much narrower (with horizontal sections narrower than the length of an adult foot) and much less safe to traverse.

And there’s more. The switch to much bigger seats means that there are far fewer seats in each of the 24 auditoriums than before. That means two things: It’s harder to get a seat you like; and, it’s much easier for some screenings to sell out. Indeed, that reduced seating capacity was cited as a plus by theater staff, who suggested to us that it’s better to sell-out a theater with far fewer seats than to have a multitude of unoccupied seats. We don’t follow that reasoning. Also, in many of the auditoriums, two aisles have been reduced to one, a change which (along with the overall reduction in seats) drastically reduces the number of aisle seats – a prized location for some of us that has suddenly become the endangered species of seating locations.

At first glance, the new seats (and re-jigged wider rows) seem to offer lots of legroom – until they are reclined, that is; then, it’s hard to make your way along the row, past somnolent moviegoers. And speaking of body-language, is it really a good idea to encourage movie-goers to lie prone at the movies? For heaven’s sake, they’re there to see a movie, not have a nap. One fellow filmgoer canvassed by this writer said the mass ‘flake-out’ looks (and feels) undignified, ‘like a pod of beached whales.’ Becoming that casual in a public place is apt to cultivate bad habits, which are already far too common among movie-goers who think nothing of repeatedly consulting the oracle that apparently resides within their so-called ‘smart-phones’ and assailing everyone in the darkened auditorium with the blinding beam of light emitted by those addiction-feeding, self-affirmation devices. Some even carry on telephone conversations during a movie – an act of such callous disrespect for others as to boggle the mind. Encouraging people to sprawl flat on their backs, as they might do in the privacy of their own homes, risks conditioning them to behave as though they were in their own homes, with a blissful disregard for the strangers with whom they are sharing the space. Too many people are already oblivious to the presence of others. Why promote the erosion of the border between a public and private space?

The ad copy proudly proclaims the arrival of “premium luxury powered reclining seats,” but its implementation – retrofitting existing theaters to house seats and hollow elevated platforms they weren’t built to accommodate – has made the recline a decline, marring, rather than improving, the movie-going experience. (The same can be said for Landmark’s earlier move to obligatory reserved seating, which prevents their patrons from arriving early for best selection and/or moving to other seats to elude some troublesome fellow filmgoers.)

Incidentally, the ill-considered changes don’t end inside the auditoriums. Privacy screens have been thoughtfully installed between upright fixtures in the men’s washrooms, which is a plus; but why on earth have the motion-detector water faucets in the sinks been replaced by manual taps? That change is not an improvement from a hygiene perspective. And the side lobbies are much brighter now, thanks to some odd new fixtures that look like illuminated strands of spaghetti thrown into the air and freeze-framed in their descent. We preferred the former, more subdued (and less harsh) lighting.

It may be an old aphorism, but it’s still valid: If something isn’t broken, don’t fix it!

Copyright © 2018 by John Arkelian.

**************************************

Movies under the Midnight Sun

© By John Arkelian

In his poem about the Yukon, “The Cremation of Sam McGee,”

“Palace Grand under the Aurora” – Copyright © 2017 by Priska Wettstein

Robert Service wrote these iconic lines: “There are strange things done in the midnight sun / By the men who moil for gold.” Nowadays, the strangest thing done under the midnight sun is the Dawson City International Short Film Festival, a four-day celebration of short films from far and wide, an international film festival only a few hours drive from the Arctic Circle that’s now in its 18th year! And the gold that’s being toiled for at that remarkable event is purely of the cinematic variety.

For the past ten years, the festival, which is an operating arm of the Klondike Institute of Art and Culture (KIAC), and which coincides each year with Easter weekend, in a bit of unique scheduling, has been directed by Dan Sokolowski, himself a filmmaker and an Ontario transplant. Come to think of it, nearly everyone in Dawson, a community of nigh only a thousand souls, comes from away. There’s something about this place that beckons to the free spirit within. And for creative people – filmmakers, writers, artists, and photographers – the town is a haven, a place where support for the arts is enthusiastic and palpable. Dawson has a writer-in-residence (who can draw inspiration from the cabins once occupied by poet

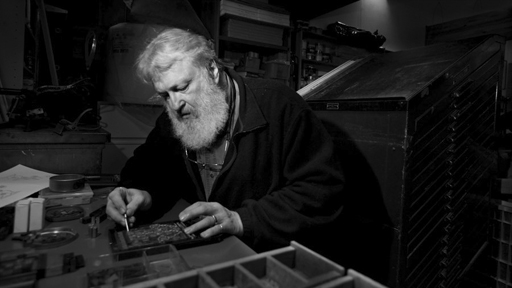

Scene from “Barbarian Press” — courtesy of Dawson City International Short Film Festival

Robert Service and writer Jack London, as well as the childhood home of Pierre Burton), and the town has two visual artists in residence at all times. It’s no wonder that the festival’s 85 short films this year play to mostly capacity crowds, and over 60 volunteers contribute 685 hours of their time to make this little festival near the top of the world such a treat to attend.

There’s none of a big city festival’s haughty hierarchical distinctions between those deemed to be a “Somebody” and everybody else. Everyone here, from VIP to regular filmgoer, mixes and mingles in an easygoing informality that puts bigger venues to shame. Opening night has the sole feature-length film. And it couldn’t be a better choice. “Dawson City: Frozen in Time” (getting its Canadian

Scene from “Observance of Yolo” — courtesy of Dawson City International Short Film Festival

premiere in Dawson) is at once a documentary history of the town, of the Klondike gold rush, and of the era of silent films. At its heart lies the story of 500 silent films used as landfill long ago and recovered from the Dawson permafrost (which preserved them) many decades later. Snippets from those self-same films were cleverly edited together to tell this documentary’s trifecta of intertwined stories.

As to the shorts, they live up to their billing as international, hailing from diverse countries around the world, and engagingly grouped according to their place of origin, moving out in concentric circles from Dawson itself: ‘Yukon Visions,’ ‘Up River,’ ‘Beyond the Aurora,’ and so on. There are plenty of promising nuggets, as well as richly

Scene from “Emma” — courtesy of Dawson City International Short Film Festival

refined gold among the shorts: “First Cut” cleverly juxtaposes eclectic trades that involve cutting – among them, a film editor, a tailor, and a butcher. “Barbarian Press” is a bibliophile’s love story, as it explores the work of Jan and Crispin Elsted, New England-based makers of gorgeous hand-made books who exemplify love for a craft – and for each other. “Emma” is the gently poignant story of a lovely 14-year old girl who is contending with the affliction of rapid hair loss. “The Talk” is a hilarious look at the sheer awkwardness of sex education from the point of view of people being instructed in the private lives of the birds and the bees. “The Observance of Yolo,” for its part, is a wry reflection on man by his best (canine) friend. “A Spark in the Dark,” one of the several strong entries hailing from Dawson itself (who’d have thought so much talent would be at hand in such a small place) is an amusing look at singles in Dawson trying to use the social media app “Tinder” for hook-ups in a place where anonymity is impossible. “Apikiwiyak” is one of several shorts reflecting First Nations perspectives and concerns, in this case, the issue of violence against indigenous women. “Second Nature: Feral” casts a spell with stop-action animation, as a house built by man gradually reverts to nature. Some short-shorts about a persistent squirrel, “Peanuts Squirrel Trailers,” are highly amusing reminders that our efforts to outwit these furry daredevils are hopeless. And director Suzanne Crocker, whose feature documentary, “All the Time in the World,” was a hit at Hot Docs in 2014, is back with a new short called “Dandelion Wishes,” which celebrates the free-spirited unconventional streak in Yukoners.

Sokolowski (and others) tell me that Yukon is not perceived to be a draw for arts and culture-seeking tourists. That’s a shame (of mountainous proportions), for here’s a place that’s rich in both – and a film festival that’s well worth traveling from afar to attend.

John Arkelian is a film critic and founding editor of Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

Editor’s Note: Our review of the sole feature-length film at the 18th Annual Dawson City International Film Festival appears below (on this page). And don’t miss our in-depth travel feature on the wonderful place known as the Yukon; it appears in the Travel section of Artsforum’s online edition at: https://artsforum.ca/travel

**************************************

“Dawson City: Frozen Time” –

A Celluloid Time-Capsule in the Permafrost

© Reviewed by John Arkelian

“Dawson City: Frozen Time” (USA, 2016) (B): This feature-length documentary had its Canadian premiere at the delightful

Still from “Dawson City: Frozen Time” (Louise Lovely in the 1916 silent film “The Social Buccaneer”) — courtesy of Dawson City International Short Film Festival

18th Dawson City International Short Film Festival in April 2017, with its director, Bill Morrison, in attendance from New York. It had its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival in the fall of 2016, and that’s mighty good company for a town of only a thousand souls in Canada’s northern Yukon to keep. The respective histories of Dawson City, the Klondike Gold Rush, and early movies intersect in a documentary that makes ingenious and entertaining use of snippets from a myriad of hitherto lost silent films. The medium coincides nicely with the message here, insofar as it is the story of a cinematic buried treasure unearthed – in the form of 533 silent films dating from the 1910s through the 1920s. Dawson was the remote last stop on the film circuit of the day, and distributors weren’t eager to pay the freight to get the movies back from such a distant locale. Consequently, prints were simply stored on site, until a decision was eventually taken to simply dispose of them. Some were burned; others went into the Yukon River. But some 500,000 feet of film were used as makeshift landfill at an indoor swimming pool in the town’s recreation building – only to be unearthed decades later, after their presence had long been forgotten. It turns only that the permafrost had largely preserved them. And it was a time-capsule treasure well worth preserving: Often, these were the only known prints extant of titles long supposed lost forever. This legacy of early filmmaking was restored by film experts in the United States and Canada, and clips from those self-same films were cleverly selected and edited together to present the intertwined stories of the town, the gold rush, and silent films. It’s a fascinating historical trifecta, and it is charmingly told with abundant wit, ingenuity, and verve. At two hours, it is arguably a tad overlong; but it grabs and holds our interest with its clever use of old film clips to tell a story that spans more than a century.

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

****************************************

January 12, 2017

Reserved Seating at the Movies Gets Thumbs Down!

© By John Arkelian

There’s an old adage: “If it’s not broken, don’t ‘fix’ it.” But it seems that cinema chains are so intent on coming up with ‘the next big thing’ to justify ever-escalating admission prices, they’ve thrown meaningful customer service to the four winds, along with common sense.

For as long as movies have been shown, filmgoers line-up, buy their tickets, and decide where to sit when they get into the theater. The new, purportedly “improved” way of doing things is to select your seat in advance, as though you are attending the ballet, opera, or a live theater production. Will equivalent pricing soon follow? The arrival of all-reserved seating at cinemas is a terrible idea. It turns movie-going into an unpleasant, over-regimented experience – robbing filmgoers of the freedom to choose where to sit when they get into the auditorium.

And there are plenty of reasons why one might want to change seats before or during the movie: It is common now, alas, for a great many people to use their so-called “smart-phones” during the movie, blithely shining a blindingly bright light into the eyes of everyone behind them. That behavior has become ubiquitous at movie theaters – and cinema staffers make no effort to stop it. (Ushers patrolling the aisles disappeared long ago.) Other people are fond of talking, rustling candy wrappers, loudly shaking popcorn containers (as though rehearsing for the percussion section in a brass band), coughing, bringing infants (who are as apt to cry as to coo in the alien environs of a movie theater) where they ought not to be, and kicking the chair in front of them (while practicing their Morse code skills on the unsuspecting back of the person in front of them). By contrast, such uncouth behaviors are wholly absent from live theater venues and concert halls, where reserved seating, accordingly, makes more sense. In short, too many people are devoid of good manners and common courtesy in movie theaters. It never occurs to them that their antics are disturbing other patrons: Filmgoers therefore need to be free to change seats at will to put some distance between themselves and the source of the disruption. It is pointless to assert that we can go fetch staff to deal with such issues. Doing so would mean spending more time in the lobby than in the theater, which rather defeats the purpose. (Indeed, if we had to find a staff person every time somebody had a brightly-lit smart-phone on, we would rarely be in the theater.)

Furthermore, some of us are fussy about where we sit: We consequently go early to get the seat of our choice. That won’t necessarily work with reserved seating. In the first place, some of us will never be reserving our seat online: It’s not at all convenient for those (few) of us who are not attached at the hip to a telecom-gadget. That leaves us with the alternative of choosing our seat at the theater. But, the imposition of all-reserved seating means that no matter how early we get there, someone might have beaten us to the punch, and scooped up our preferred seat from afar – by reserving it online from offsite, perhaps days before we ever arrive at the theater. Reserved seating penalizes those without smart-phones or the wherewithal to reserve seats online – turning us into second class customers. The previous system – of general admission seating, with seat choices made in the theater itself on a first-arrived, first-served basis – is the only sensible and fair one.

The theater chains assert that filmgoers “love” this new “service,” but they are dead-wrong – judging by the irate reactions we have witnessed at the check-in desk over and over again. The verdict has been far, very far, from approving: Rather, when confronted with the unwelcome new fait accompli, a great many filmgoers have been moved to loudly vocalize their resolute view that reserved seating at the movies is an awful idea! “This is ridiculous!” are words we have heard repeatedly at theaters in the wake of the change. Bring back general admission seating – or, at the least, do what airlines do, and restrict advance offsite seat selection to a finite period (of, say, 45 minutes) prior to show-time. Reserved seats are assigned seats: Give us back our freedom instead.

And, please, while you’re at it, get rid of the commercials which currently assail your audience. Paying customers should not be subjected to an advertising blitz before the show they’ve paid a lot of money to see.

John Arkelian is an award-winning journalist, author, and film critic for Artsforum Magazine.

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

**************************************

Face-to-Face with the Triune God

© By John Arkelian

“The Shack” (USA, 2017) (B-) is the film adaptation of the bestselling novel by William Paul Young about a man who is stricken with grievous pain over the sudden loss of his child. He descends into what he calls “The Great Sadness,” and its dark pall threatens to unravel his family and his faith. How can we reconcile the worst things in life with our faith in a loving God? Life inevitably brings with it a litany of bitter losses: They cause us pain, and sometimes it feels unbearable. It’s bad enough if illness or accident steals a loved one from us; but what if human evil does so? It’s a question as old as man’s inhumanity to man, a question which was doubtless murmured in the death camps of the Holocaust, in the killing fields of Cambodia, Rwanda, and Bosnia, and in the misery of today’s Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and South Sudan. And, not just in far-away lands: Violence, abuse, and neglect are as close as our own communities. Wherever man’s wickedness causes torment, enslavement, injury, or death to another, we cry out: How can God allow this? Why does He not intervene on behalf of the oppressed and victimized?

In “The Shack,” a family is robbed of their youngest daughter when she is taken from a campground. (The victim of a serial killer, her remains are never found.) The pain that causes her family closes them off from love and hope. As the child’s father, Mackenzie (Sam Worthington) blames himself for failing to protect her. A cryptic note draws him back to the mountain shack where the crime occurred. The note is signed ‘Papa,’ the affectionate term Mackenzie’s wife Nan (Australia’s always watchable Radha Mitchell) uses to refer to God. Something – is it a glimmer of hope, or the last gasp of despair – takes Mackenzie back to the mountain. Winter suddenly turns to summer, a dilapidated ruin becomes a spacious home made of hewn logs, and nature is in full bloom. There he meets ‘Papa,’ in the form of a jolly black woman (Octavia Spencer); her son (Avraham Aviv Alush), a Jewish carpenter who greets the newcomer as a long-lost friend; and an ethereal young woman (Sumire Matsubara). They are, in fact, the film’s depiction of the Holy Trinity – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. And their purpose is help Mackenzie free himself from the sadness, anger, guilt, and grief that threaten to drown him.

Their revelations are as gentle as their welcome is warm. How refreshing to see God presented as our loving parent (and, through Jesus Christ, also as our sibling) – a parent who loves each and every one of us unconditionally, respecting our free will while seeking only to share His love. The film asks why bad things happen to good people. Its answers to that mystery may not be complete, or completely satisfying. Neither may its homey portrayal of God be all there is about God: Majesty, awe, and reverence are put aside in favor of companionship and the ultimate familial bond. But there is food for thought here, and considerable comfort – in bringing God down to earth in a way that makes Him accessible and familiar. Shot in Canada, the film has a solid cast, with Graham Greene and Alice Braga in supporting roles. Sometimes the didacticism gets too overt; and neither the narrator nor the flashback structure is needed. But the film’s occasional awkward moments pale in comparison to its touching ones – and in its warm depiction of the God of love.

John Arkelian is an award-winning author and journalist

Copyright © 2017 by John Arkelian.

**************************************

When Bad Things Happen to Good Puritans:

Superstition as the Dark Side of Dogmatic Religiosity in “The Witch”

© By John Arkelian

“The Witch” (USA/U.K./Canada/Brazil, 2016) (A): Here is one of the best movies of 2016. But be warned, it may not be for all tastes. It’s the grim story of a family of Puritan settlers expelled from their 17th century New England colony for failing to conform. A man, his wife, and their four children set out to create a new home for themselves in the wilderness. Then, bad things, seemingly inexplicable things, start to happen to them. Is some malevolent supernatural force preying upon them? That’s what their rigid and dogmatic religious views cause them to wonder. The story focuses on the eldest daughter, played by Anya Taylor-Joy, as she contends with fear, suspicion, and mounting dread. The result is a foreboding but utterly engrossing fable – smart, beautifully acted, relentlessly dark in tone, and highly original. The cast is first-rate, with Anya Taylor-Joy as Thomasin, Harvey Scrimshaw as her brother Caleb, Ralph Ineson as the father (William), Kate Dickey as the mother (Katherine), and Ellie Grainger & Lucas Dawson as the twins, boisterous children who have the ever more abrasive habit of reciting unpleasant rhymes about the family’s black goat and its supposed whisperings.

The film, from writer/director Robert Eggers, has northern Ontario filling-in for New England. “The Witch” is a truly creepy film and a memorable one, despite a significant misstep: It shows (or seems to show) us, but not its hapless family under siege, a physical cause for their troubles – a cause that cannot logically be there. Or, do our eyes deceive us? Is what we seemingly see just an externalization of their fears, a manifestation of what these characters imagine must be there, a representation of superstition as the dark side of dogmatic religiosity? Better to have left the actual agent of their misfortune to our imagination: Is it mass hysteria? Is it superstition born of extreme misfortune and unbearable tragedy? Or is it something supernaturally wicked that this way comes?

Subtitled “A New England Folktale,” “The Witch” is a journey into the unconscious, a story of determination and faith colliding headlong with grievous misfortune and loss. It touches on the power of suggestion, the very human tendency to look for scapegoats, and the blurring of the line between reality and fairy tale in the minds of these 1630 Calvinist Puritans. A word of warning: Some of the film’s content is disturbing; but, this film is mesmerizing, if you can brave the darkness. “The Witch” won Best Director at Sundance, where it was also nominated for the Grand Jury Prize. It was nominated for Production Design by the Directors Guild of Canada. It has one of the most effective trailers we’ve seen in years (winning in its category at the Golden Trailer Awards), which has inexplicably been omitted from the DVD’s too skimpy extras. For ages 18+ only: Disturbing content and violence.

***************************************

Down in the Bayou:

Coming Face to Face with Society’s Other

© By John Arkelian

“The Other Side” (France/Italy, 2015) (B): Here we are in the summer of 2016, in the midst of a US presidential election which pits a bloviating boor and bully, who is manifestly unfit to even be considered for the highest office in the land, against an opponent who is widely mistrusted and disliked, however ‘entitled’ she seems to think she is to the top job. It makes us wonder, “What has the country come to that we are reduced to these unsatisfactory choices for chief executive?” Candidates (in America and just about everywhere else) with integrity, humility, real decency, and the wisdom, instincts, and grace of a statesman are in alarmingly short supply. Why is that? There’s clearly a longing for someone who’s not part of the status quo establishment; but the leading contender is the Establishment Woman writ large. Are these two candidates (one of them underwhelming, the other positively distasteful) the best the big parties can offer? With such questions in mind, it is useful to reflect on the presence of other attitudes within our own society.

Here’s an up-close-and-personal look at one corner of the underclass in our midst. Italian documentary filmmaker Roberto Minervini takes us to the bayous of rural Louisiana. The people we meet are poor, but they aren’t just poor. They are also coarse, given to harsh talk, ignorant (or, at best, unsophisticated) attitudes, and an undue fondness for either drugs or guns. This is a sector of the marginalized we’re mostly unaware of. And, don’t get smug about it: America has no monopoly on this sort of underclass. For about two-thirds of this film, we spend time with a rough down-and-outer. He’s a convicted felon (presumably for drug-related offenses), who describes himself as ‘a pimp and a drug-seller.’ The first of those self-bestowed titles seems to be empty braggadocio, but he certainly uses drugs – snorting cocaine, ‘cooking’ other narcotics, and even injecting a pregnant stripper with heroin. His crude language and cruder views of the powers that be leave us very little with which to identify. He and his circle seem tailor-made for the disapproving moniker of ‘white trash.’ How the filmmaker gained such intimate access to his daily life – nudity and sex are open and shameless, severe cussing and drug use are wanton – is a mystery. Indeed, you’ll be hard pressed to believe that this is a documentary film. There is no narration, no editorial comment, no intercession between us and these rather unpleasant characters.

Vices are on open display here, but we get the sense that they are the product of deprivation and consequent desperation. It doesn’t make the vices, the coarseness, the vulgarity and crudeness, or the retrograde attitudes any the more palatable to the ‘civilized’ middle class viewer, but it helps us perceive these coarse folks as much as victims as undesirables in polite society. And, however, distasteful their behaviors and attitudes, we surely can find commonality with the humanity that peeks though. Playing himself, Mark Kelley, is tender, loyal, and kind with his ailing mother, aged grandmother, and siblings. There’s love between him and his girlfriend (Lisa Allen), however debased their lifestyles and talk may be. There are moments of poignancy: Mark says, “Every day’s a good day,” as if to persuade himself that that were so; a minor (perhaps Mark’s nephew) stands quietly at an armed services memorial for fallen soldiers; and a girl at a Christmas picnic sings an a cappella hymn. There’s also irony here: Mark wants to sober-up and concludes that only a few months of incarceration will make that possible. Meanwhile, an old man, with whom Mark does blue collar piece-work, rambles on about the importance of freedom, though he seems to use his only to remain in a state of permanent drunkenness. Still, even there, a touching moment peeks through, when the old man points to an inspirational message from some well-wisher posted on his refrigerator. It says: “To all those who feel worthless, you’re worth the world to me.” And there are puzzles here: When we first see Mark, he’s walking along some deserted back-road stark naked. When it comes time to part company with him, we see him put on a suit jacket, only to strip to his privies in the forest. Why, we are not told, though it seems a symptom of emotional dysfunction. There’s ugliness amidst this underclass, but the film takes aesthetic pains with the lighting and camera angles to present pleasing pictures of Mark paddling through a swamp or standing in the sun-dappled woods. Documentary realism mitigated by moments of staged aesthetic beauty? Perhaps.

The last third of the film abruptly switches gears. We leave Mark alone in the woods and join in his stead a small group of men who are training themselves as a self-styled militia, arming against the feared imminent take-over – by Obama, the U.N., or just a rogue US government. They shoot targets (including an effigy of Obama), practice stalking imagined foes in paramilitary formations, and unwind with a rowdy hootenanny (wet tee-shirt contest and an extremely crude sexual pantomime included). Their leader is actually quite articulate, but, it is a tad unsettling to hear his distorted views of what he takes to be geopolitical realities. As a DVD extra, we get an interesting four and a half minute deleted scene with a protest in Texas in favor of so-called “open-carry” laws. For the urban middle class viewer, the scene speaks for itself: Protesters include a woman with a babe in arms, as well as a father pushing a baby-stroller while he has a long gun slung over his shoulder. Such tableaux seem alien, disconcerting, and retrograde to us. But they seem as natural and benign as breathing to these folks – the same folks, alas, who persuade congressmen and courts to take Second Amendment rights (to ‘keep and bear arms’) to absurd extremes: For this is ‘the other side,’ a lifestyle and mindset that seems unfathomable to us but which is enthusiastically embraced by others. As appalled as we may be by some of the lifestyles and attitudes presented in this film, we also get to see these people as people: Even the most degraded and/or deluded among us still have the same loves, worries, and frailties as the rest of us.

“The Other Side” is a remarkably candid (not to mention utterly unvarnished) look at some specific corners of the underclass and the marginal. It’s not pretty. On the contrary, the lifestyles and outlooks depicted here are coarse, crude, and raw. These bayou folk are far removed from polite middle class society, let alone a sophisticated intelligentsia. The man and woman whom we follow for much of the film are far (very far) from paragons. But they demonstrate the love, pain, loss, and endurance common to all of us – and that’s enough to create common ground and sympathy. The DVD would have benefited from subtitles, as bits of the dialogue are occasionally hard to clearly make out due to accents. “The Other Side” was nominated for two awards at Cannes, including Best Documentary.

Warning: For ages 18+: Very coarse language; graphic nudity; strong sexual content; graphic drug use; and brief disturbing content.

***************************************

Nothing New Under the Suns:

“Star Wars” Redux in “The Force Awakens”

© By John Arkelian

“Star Wars: The Force Awakens” (C+): The seventh film in the franchise launched in 1977 hearkens back to that first film in plot and style. It has a couple of good moments, but mostly it just underwhelms, precisely like the overrated original film did. It can’t live up to the tsunami of hype; and like all but one of its predecessors, it can’t even live up to its musical score (the good bits of which are all borrowed from previous outings). The music is full of portent and rousing emotion; the movie, not so much. This is the first outing without the involvement of franchise originator George Lucas (he sold the franchise, kit and caboodle, to Disney for billons). But so-called wunderkind J.J. Abrams brings nothing memorable to the mix as this installment’s director. (For us, rumors of Abrams’ movie-making magic have always been greatly exaggerated: Witness his heavy-handed ‘reboot’ of “Star Trek,” which, heavy on noise, action, and effects, and light on everything else, bears precious little resemblance to its illustrious forbears.)

The goal here, very clearly, is to recapture the supposed magic of the first film. A young adult with untapped potential on a backwater planet gets drawn, as if by fate, into an adventure of galactic import. Along the way, our protagonist learns of “the Force” and of powers (incipient telepathy, telekinesis, and a remarkably sudden aptitude for swordsmanship) she never suspected she possessed. And, yes, this time out, the fresh new hero-in-the-making is a she – in the person of “Rey,” who ekes out a marginal solitary existence as a scavenger on a desert world. We learn little about her (she was separated from her parents as a child and stubbornly awaits their return), except that she is strong-minded and resourceful. She also has a sound moral compass, rescuing a droid in distress, an act which unites her with the film’s cute rolling sphere of a smart-bot, named BB-8, and, in the process, changes her life. British actress Daisy Ridley invests the character with appeal, despite the script’s skimpy attention to characterization. BB-8 had all the makings of a cloying or silly character, but it actually is one of the film’s strengths, along with Rey.

Indeed, some of the early scenes of Rey making her way through the immense dead hulks of fallen Imperial Star Destroyers have a haunting quality – the derelict man-made behemoths lay deserted and forgotten, along with the hubris and aggression they embodied, amidst the sand dunes. Even a simple, quiet scene of Rey sliding down a towering dune on a make-shift sled, has a surprisingly poignant quality. If only such moments would last. Soon enough, they are displaced by new, improved war machines, aerial dogfights, shoot-outs on the ground, captures, escapes (more than one of each), and a series of crossed paths with allies and foes alike. Rey is far and away the most interesting newcomer; though John Boyega’s Finn, a Stormtrooper with a conscience who switches sides, garners some of our sympathy as everyman out of his depth. His fears and uncertainties are things the rest of us can relate to; just as we aspire to follow his example and step up to challenges he never imagined he’d be called upon to face. On the other hand, the fact that both he and Rey are able to adroitly wield a light-saber (a weapon neither of them has ever seen before, let alone used) the instant they pick one up utterly beggars belief.

Elsewhere, Lupita Nyong’o voices Maz Kanata, a diminutive stand-in for Yoda: She’s not a Jedi master, but she’s small and computer-generated, as well as being old, eccentric, wise, and a bit funny-looking. S omething tells us we may be seeing more of her in later installments. Oscar Isaac is okay as an ace fighter pilot Poe Dameron, a role that is more stock-type than fully realized person. On the down (may we say dark) side, there’s Adam Driver, who is badly miscast as Darth Vader wannabe Kylo Ren. He’s all dressed in black, with a seriously pointless mask, but he’s no Vader. Darth Vader and Obi-wan Kenobi were the truly memorable characters from the earlier films. Vader was the epitome of the dark knight, bringing elegance, mystery, and sinister power to his role of uber-villain. But the new pretender to that role has no gravitas whatsoever; he’s more of a whining poseur stuck in adolescence: ‘Alas poor Vader, I knew him not.’ His motivation? He just wants to be evil to spite his parents. Really?

Domhnall Gleeson, who (along with Oscar Isaac) was so good in this year’s “Ex Machina,” plays a one-dimensional, half-rabid general, practically foaming at the mouth as he delivers a gloating sentence of doom that will destroy millions. Several cast members from the first three movies make an appearance here, though few play a significant role in the story. The two who do – Harrison Ford’s Han Solo and Peter Mayhew’s Chewbacca – are as good here as ever they were in earlier installments. The rest of the veteran cast have very little to do – though Carrie Fisher (as Princess Leia) and Anthony Daniels as the gold-plated mechanical comedian C3P0 fare better than R2D2 and especially Mark Hamill (as Luke Skywalker), the latter making only an absurdly brief appearance in a tiny cameo. Newcomer Max von Sydow, an actor with real chops, is sadly underutilized. For her part, Gwendoline Christie (“Game of Thrones’” noble warrior Brienne) is utterly wasted in a ridiculous role of a chrome-plated martinet. Strutting around in her shiny silver plated helmet and cape (like a filmmaker’s clumsy hybrid of long-gone villain Boba Fett and a Stormtrooper), she’s as much a silly poseur as the supposed junior dark lord, Kylo Ren. Even her character’s name, Captain Phasma, is too dumb for prime time. But that’s nothing next to the nomenclature employed by the new evil emperor in waiting, the overblown, cartoonishly-named ‘Supreme Leader Snoke’ (voiced by Andy Serkis of Gollum fame). Snoke? Sounds like a card-shark or leader of a pack of (actual) rats.

If the characters are a mixed bag (some showing potential, others not so much), they are far better than the film’s half-baked, seriously underwhelming plot. The whole things revolves (well, weakly limps) around a quest. A quest for a map. Will it show the way to treasure? No. To a weapon of unimaginable power? No. To the answers to questions that have haunted mankind for ages? Nope. Just the possible whereabouts of Luke Skywalker, who quit the scene years ago, in dismay at the parlous state of galactic affairs. Why a man who wanted to disappear would leave a map showing precisely where he went is a mystery the script does not address. And why everyone is so obsessed about finding him is never convincingly explained. If the outcome of the grudge rematch between good and evil is so dependent upon him, why didn’t he make some real impact when he was still around?

Here we venture into the story’s heavy-handed disregard for internal logic. Some 30-odd years ago, in the first group of films that culminated with “Return of the Jedi,” Luke and friends destroyed the evil Emperor, blew-up his second Death Star super-weapon, defeated the Imperial fleet, and redeemed the Dark Lord of the Sith, Darth Vader, who before his seduction by the Dark Side had fathered Luke and Leia, unbeknownst to himself. Cue the celebrations: Ding, dong, the witch is dead. The Empire, it seemed clear, was fallen, along with its wicked mastermind. So why has the Rebellion of those days morphed into the Resistance of this film? Who are they resisting exactly, and why? They are allied to the New Republic, which is the restored democratic government that resumed operations after the tyranny was overthrown. If the Republic has been restored, and it has, then why is a Resistance necessary? The script skirts this awkward question by disposing of the Republic in one fell stroke. And what about the new bad guys in town – the First Order. Where did they get the Star Destroyers and the armies of Stormtroopers? What’s their raison d’etre, other than the professed one of ‘finishing the work’ started by Vader & Company? Is wrecking havoc, with wanton death and destruction, in the apparent absence of any governmental legitimacy or discernible ideology, sufficient motivation? No, but then the film doesn’t care about reasons or explanations. They exist (how or why doesn’t seem to matter). They’re bad. And they have to be fought.

The trouble is that besides being arbitrary and heavy-handed, this state of geo-political play is kind of depressing. If a renamed Empire still exists, with massive resources behind it, the momentous victory of the earlier movies is reduced to meaninglessness. Same bad guys with new names: Nothing’s changed; nothing’s been accomplished by past heroics. And we get only the most superficially unconvincing explanation for the absence of a new crop of Jedi knights. On the plus side, though, light-saber duels never grow old. The chief one here is even invested with some tangible emotion: It has some real power as a result. Trouble is it is sorely diminished by its outcome.

The Millennium Falcon spaceship makes a welcome (and surprising) return. But too much else smacks of the series’ trademark gratuitousness: Gratuitously odd looking aliens, gratuitous shoot-outs (as between competing gangs aboard an old freighter), and the usual, been-there, done-that, whoops and hollers during dogfights. Too much here is derivative of the earlier films, especially the first one, in its blatant attempt to recapture the energy and vicarious excitement of that first film. (Truth be told, though, the second film in the series, 1980’s “The Empire Strikes Back,” far exceeded the original film in every way – including creativity, gravitas, and surprises – and it remains the only truly memorable film of the whole lot. “The Force Awakens” has more of the series’ hidden familial bonds, followed by a shocking surprise of its own; but it’s an unwelcome one for viewers. The result is a moderately entertaining film that hews closely to the unambitious movie serial formula loosely dressed in an amalgam of action/adventure, ‘low sci-fi,’ and comic book conventions. It’s no more involving than its made-for-television animated cousins (like “Star Wars: Rebels”), superficially (and mildly) entertaining, yes, but rarely rising above mediocrity in terms of storytelling. It’s not bad, but not memorable; it’s also not very ambitious and not worthy of all of boisterous, fawning hype.

Copyright © December 2015 by John Arkelian.

**********************************************

“Phoenix”

© Reviewed by Milan Paurich

“Phoenix” (A): Post-WW II Berlin. Nelly (Nina Hoss), a concentration camp survivor, returns home after having suffered a gunshot wound to the face. (No explanation is given as to how it happened.) After reconstructive surgery that leaves her looking like her old self (but, y’know, different), she embarks upon a mission to locate the husband who may – or may not have; she’s not really certain – have denounced her to the Nazis. Does she still carry a torch for him, or is revenge in the offing? ” Phoenix,” the latest triumph by critics’ darling Christian (“Barbara”) Petzold, keeps us guessing, and the suspense is both unnerving and delicious.

When Nelly and Johnny (Ronald Zehrfeld, fantastic) finally cross paths he doesn’t recognize her. (Like I said, she kind of looks like her old self only different, and she’s now going by the name of Eva.) Her passing resemblance to Nelly gives Johnny (“Call me Johannes”) an idea, though. If Eva pretends to be Nelly, she’ll be able to claim the inheritance being held by occupying Allied forces. They can split the money 50/50, then go their separate ways. You don’t have to have seen a lot of 1940’s Hollywood film noirs to know how this is going to end. Everything builds to a climactic scene so flat-out incredible, so fraught with conflicting, ricocheting, transcendent emotions that it ranks with the greatest moments in cinema this decade.

Some have criticized “Phoenix” for trivializing the Holocaust by making it the back-story of a romantic thriller in the “Vertigo” tradition. But this very real historical setting only enhances, ennobles even, the dramatic ballast of the characters. Of course, “Phoenix” is a movie that is haunted on multiple fronts. Besides the starkness of a (still) war-ravaged city and horrific memories of the camps that stalk Nina and fellow survivor Lene (Nina Kunzendorf, quietly touching) like malevolent ghosts, there’s the whole specter of the German New Wave to contend with. Specifically, the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, that filmmaking movement’s brightest light. The baroquely stylized Berlin recalls Fassbinder’s biggest hit, “The Marriage of Maria Braun.” Plus, the nightclub (the titular Phoenix) where a good portion of the movie takes place (Nelly was a singer and husband Johnny accompanied her on piano) is richly evocative of the hothouse cabaret atmosphere of both “Lola” and “Lili Marleen.”

Petzold and his muse/preferred leading lady Hoss (one of the finest screen actresses working today) have always had a kind of Fassbinder/Hanna Schygulla sort of vibe going for them anyway, which makes the comparison both inevitable and irresistible. (Hoss also starred–brilliantly–in Petzold’s “Barbara,” “Jerichow” and “Yella.” If you haven’t seen them, what are you waiting for?)

The key artistic difference between Petzold and Fassbinder isn’t simply a matter of heterosexual versus homosexual sensibility. It cuts much deeper than that. For Fassbinder, genre (especially domestic melodramas like the ones his cine-god Douglas Sirk used to make) was a prop, a tool, a way to explore his pet theme of emotional fascism and how it poisons virtually every relationship: men/women, men/men, women/women, parent/child. Because Petzold is a film nerd who digs rummaging in the past (think of him as the Coen Brothers’ long-lost Teutonic sibling), genre is akin to a toy box. And with the Hitchockian trappings of “Phoenix,” he’s found a really cool playground to roam around in. One thing’s for certain. Petzold is the best thing to happen to German cinema since the halcyon days of Fassbinder, Herzog and Wenders.

************************************************

“A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence”

© Reviewed by Milan Paurich

“A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence” (A): “We want to help people have fun.” That line is repeated at various times throughout Roy Andersson’s “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting Existence” by an itinerant novelty salesman. While the old crone never quite makes good on that claim – for starters, he and his equally morose partner are probably the worst salesmen who ever lived – Andersson does, and then some. Of course, your idea of fun might not be the same as mine, or Anderrson’s for that matter, so caveat emptor and all that.