Father Goose: Remembering Bill Lishman

© By Bill Eull

Bill Lishman and feathered friends flying into the sunset — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

It was the eyes, I think, that caught you first. I don’t mean the first time you met Bill but anytime you crossed his path. You’d notice the shiny alertness and then you’d see the delight: he’s glad to see you. And that’s when you recognize the extra meaning in the look: he has a story to tell. He is tickled to tell it. He wants you to hear it. And then you are both underway.

I met Bill Lishman over a quarter of a century ago. The first time I saw him was a little earlier than that. On my way to work, driving along Island Road in Port Perry shortly after dawn, I saw him flying overhead in his Easy Riser, with maybe a dozen geese ‘vee-ing’ off on either side. I was in awe. Bill Lishman drew that same awe from millions of people in those days as he worked his way to a solution to

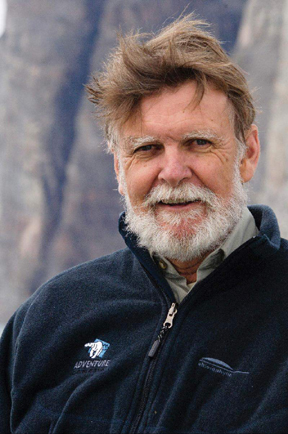

Bill Lishman — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

the questions: “I wonder if we could train birds to overcome their historical migratory patterns which took them through dangerous hunting areas?” And, “I wonder if we could teach them a better route?” What he discovered was that “We can…and we did”.

But he didn’t start out with that pair of questions. It all started with a boyish wish to fly. To be with the birds. Bill grew up on a farm in a family that had great reverence for the land and for Nature. He absorbed those values and made them his own. He teamed those values with an intense curiosity and powerful urge to action. He was always doing things. Sitting still was not an option. He had trouble in the classroom. He wanted to get his hands on things. It was later realized that he was dyslexic, but by then he had turned his focus and restless energies toward the wonders of nature and the environment.

His yearning to fly took him, at 13, to air cadets. He drilled with his unit, taking the classroom demands with a self-discipline he hadn’t discovered in regular school. He worked to get into the pilot’s seat. He did well until he took the physical. He was found to be colour-blind, an impediment to flying in the military or even in commercial aviation. He was devastated and frustrated. But he refused to give up on the dream of flight. He discovered gliding, a form of flying that required no licence. He took lessons. His instructor has since said that he was his worst student (he always did things his way) and his best (he used flying to accomplish important things).

Bill bought a fixed-wing glider, large enough to carry a man. He found suitable hillsides up which he tugged his glider. At the top, he would wait for an updraft, launch himself into it and hope. He crashed a lot. When, after a while, he got tired of the crashing and pulling, he figured out how to attach a small motor to his glider, which by that time, was a bi-wing Easy Riser. He was the first Canadian to accomplish this. The engine allowed him to launch without the need for hills and updrafts. But it didn’t save him from crashing. He ruined some aircraft (but not himself, perhaps miraculously). When he mastered the skills to get and keep his craft in the air, he had at last found a form of aviation from which nobody could bar him because he was colour-blind.

Father Goose (Canadian artist, inventor, and visionary Bill Lishman) with geese and ultralight — photo courtesy of The Lishman Collection.

Now that he was in the air, he turned his attention back to the birds. He was deeply moved when it occurred to him that his ultralight aircraft could match bird speeds and that he could birds from the top and side, unlike the earthbound view that only saw them from below. Now he could see the muscles moving. The artist and sculptor in him became riveted by what he saw. He sketched, made movies, took photographs. He treasured this new perspective on birds, their flight, and their mechanics. He became a student again. He studied ‘imprinting,’ the newly hatched chick’s instinctual adopting as parent the first living thing it sees. He decided to work with geese. They were big enough, flew at the right speed, and were interesting socially. He became ‘Father Goose.’

Having put so much focus and exertion into becoming Father Goose, Bill had to find a way to make those accomplishments worthwhile. That was the way his brain and heart worked. Once it was clear that he could indeed get a flock of geese to learn and retain a new migratory route, he was open to suggestions from naturalists that perhaps these new skills could be employed to save the almost totally extinct Whooping Crane. The rest is history. The Whoopers are, very slowly but definitely, increasing now that they are flying through much safer migratory lanes, taught using Bill’s methods.

While he was heavily involved with the bird experiments, he put his flying skills to other uses, as well. From his ultralight, he captured spectacular photographs of his beloved Oak Ridges Moraine, a geological marvel that runs north of Lake Ontario. Bill worried about its vulnerability to rampaging development. He published a coffee-table book containing hundreds of views “from above.” Bill was clear: the moraine was in grave danger and it needed to be taken seriously. He wrote the book because he wanted to make the moraine into a ‘rock star.’ That would make it less vulnerable. He had the same worry about the destruction of prime farmland around Toronto to provide ever more housing for the growing metropolis. He flew banners in protest, supported environmentalists in their causes, and was highly successful at drawing the community’s attention to the issue.

Just as Bill had a need to fly, it seems he had a need to burrow. He designed an intriguing underground home, based on the principles of the igloo – domed, interconnected, and round. He demonstrated that such a building could be practical, comfortable, and economical to run. In his later years, worried about the housing plight of Inuit people, he designed a large igloo-like housing unit that would accommodate over 40 families. While Bill has passed on, this housing idea has not. It is circulating among the powers-that-be and may yet come into being. Bill’s detailed drawings and descriptions of the innovative construction techniques required are available for study.

Bill’s naturalist bent and his passion to fly are well-known. But Bill was an artist, too. He was a carver and sculptor. He never lost his childhood need to get his hands on things, to shape and make them into something new. He was prolific. His major works, large bronze statues, mostly of animals or people in motion, were highly collectible and reside in personal collections and on public grounds throughout the world. He built an enormous structure depicting people in motion for the Vancouver World’s Fair. He created the dragons for Canada’s Wonderland. He again drew attention to himself when he created, in his backyard, a full-sized, exact scale “lunar lander.” It was bought and installed for public view in Tokyo. Today, it graces the Oklahoma Aviation and Space Hall of Fame. Recently, a very significant work was installed at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa: made of polished stainless steel, his “Iceberg” is 13 metres tall.

For a dyslexic, colour-blind kid who didn’t do so well in school, Bill didn’t turn out so bad. He wrote a best seller called “Father Goose” that was translated into four languages and turned into a very popular movie (1996’s “Fly Away Home”). He was bestowed with two Honorary Doctorates – one by Niagara University in New York, the other by Ontario Tech University. He was awarded with Canada’s Meritorious Service Medal by the Governor General. The U.S. National Wildlife Federation presented him with their Conservation Award. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. In January 2020, their journal, Canadian Geographic, identified the nation’s 90 greatest explorers. Bill was one of them. He was also a Fellow of the Explorers Club, who gave him their highest honour, the Stefansson Medal. And, ‘Odyssey of the Mind’ presented him with their Creativity Award

Bill lived with enormous energy and passion for understanding nature and preserving it. He could see its wonder, and he found ways to capture it so we could appreciate it, too. He was the best raconteur I have known: his stories were engaging and funny and his jokes were usually at his own expense. He was an adventurer who had the grace to bring his adventures and discoveries back to us so we could be inspired and uplifted. Bill’s stories were fun, but the real gift was the warm inclusive sparkle you invariably saw in his eyes.

Bill Eull, Ph.D., C. Psych. is a retired clinical psychologist and a long-time friend of Bill Lishman.

Copyright © 2020 by Bill Eull.

Editor’s Note: William Lishman (1939-2017) lived and worked near Port Perry, Ontario. A sculpture commemorating him is planned for that town’s Palmer Park, on the shores of Lake Scugog. For more, visit: https://scugogarts.ca/bill-lishman-memorial-project/

*********************************

To Fly Without Wings: The Royal Horse Show

© By John Arkelian

“O, for a horse with wings!” (William Shakespeare, “Cymbelline”)

Horse wrangler extraordinaire Guy McLean (courtesy of The Royal).

Now in its 91st year, The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair and Horse Show is the premiere event of its kind in Canada, bringing country and city together in a celebration of all things agricultural and equine. 340,000 people are expected to attend this year’s ten day indoor fair near the downtown of the nation’s largest city. Visitors can wander through stables and impromptu barnyards to observe horses, cows, chickens, pigs, and rabbits (some of which more closely resemble science fiction’s ‘tribbles’ than the more conventional looking mammals most of us are used to), and award-winning gourds of enormous proportions. There are culinary samples from Ontario’s important ‘agri-food’ industry (culled, for example,

Four-time Canadian champion Yann Candele on Showgirl (courtesy of The Royal).

from the province’s cheeses and berries), an array of leather products on sale, sculptures made of butter, a display of 332 eggs gleaned from a single hen over the course of 52 weeks, and judging contests of livestock and canines. But the jewel in the Royal crown has to be its Horse Show. Beloved of horse-set insiders and lay-folk alike, it is guaranteed to please one and all.

On Saturday, November 2nd, the highlight of the show was a horse trainer from Down-Under. Australian Guy McLean is horseback kin to his fellow countryman Steve Irwin, the late wildlife expert who was better known to

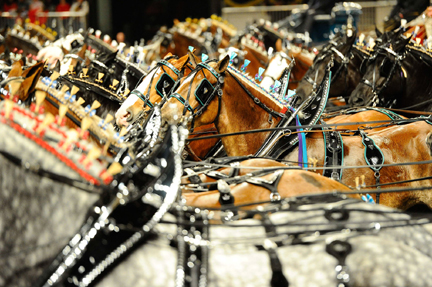

Courtesy of The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair & Horse Show

his television fans as the “Crocodile Hunter.” (There’s a dash of Paul Hogan’s “Crocodile Dundee” in him, too.) McLean’s milieu is the equine rather than the reptilian, but he shares the same infectious enthusiasm, energy, and humor as his fellow Aussie. Mounted on one of his five horses, McLean does a slow-motion pantomime of galloping, then plays traffic cop for his quartet of riderless horses. They respond to his gentle urgings like well-behaved children; and the result is utterly charming, not to mention astonishing! One horse lies calmly prone while three others stand over it, straddling its recumbent body. McLean and his mount canter on the spot, then they hop across the ground (48 times!) in a prancing move McLean dubs “flying

Courtesy of The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair & Horse Show

changes.” And there are equine calisthenics and horseplay galore, with man and horse moving sideways, diagonally, backwards, forward, and every which way at all. McLean’s élan is irresistible, and his act is worth a visit to The Royal all on its own.

But, there’s more, so much more. Two-horse teams of imposing Clydesdales pull ornately gleaming wagons. Amber Marshall, star of CBC Television’s “Heartland” introduces a rodeo demonstration, with four young girls swirling lassos in a western variation on rhythmic gymnastics and two older girls racing by with trick-riding stunts, hanging from their saddles in true dare-devil fashion. Then bundles of energy and speed known as Jack Russell terriers tear across the ground in hot pursuit of a lure, though the pups among their number have minds of their own about the rules of the race. Then eleven contestants vie for ribbons in an event in which single hackney horses pull small carriages. (Things take a briefly disturbing turn, when the prize-winner crashes head-first into a barrier — happily without incurring any harm.) Next up are the 1900-pound percherons, pulling two-wheeled carts. The evening show starts off with “eventing” in which riders essay an obstacle course: One of them, Olympic silver medalist Jessica Phoenix, has a bad spill after her horse hits the bars on the last hurdle, but her inflatable vest (a kind of portable airbag) saves the day. The jumping competition to come is the night’s flagship event, with numerous competitors taking on the 15-gate course. One favorite with this observer is the black horse Bobby (ridden by Christian Sorenson), who’s fond of running with his tongue lolling out, and whose red ribbon adorned tail warns that he’s a kicker. Canadian star Ian Millar makes an impression atop Star Power; while the curious conjunction of nomenclature between Beth Underhill and her mount Viggo won’t be lost on aficionados of the cinematic version of “The Lord of the Rings” (Underhill is the traveling pseudonym for Frodo Baggins, and Viggo Mortensen is the actor playing his guide Strider). But the night belongs to Yann Candele atop Showgirl; together they claim the prize as four-time Canadian champion. In a rare quiet moment, a proverbial wag in the balcony, musing about changes to The Royal over the years, says that, “I miss the parade of moth-balled ball gowns.” And, as dressage is not on the on agenda on Saturday evening, we miss the wondrous sight of a horse dancing on tip toes. But, what we do see amazes, captivates, and enchants.

Copyright © November 2013 by John Arkelian.

The Royal Agricultural Winter Fair and Horse Show runs from November 1 – 10, 2013 at Exhibition Place in Toronto. Visit The Royal at: http://royalfair.org/